Howdy, Stranger!

It looks like you're new here. If you want to get involved, click one of these buttons!

Categories

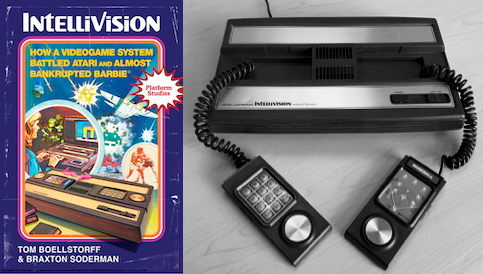

Book: Intellivision by Tom Boellstorff and Braxton Soderman

Tom Boellstorff and Braxton Soderman's Intellivision: How a Videogame System Battled Atari and Almost Bankrupted Barbie® is our featured book discussion for this week. The book is available from the MIT Press in paperback / ebook, and also open access PDF.

Left: cover of the _Intellivision (2024) book. Right: black and white photo of the Intellivision videogame system._

From the MIT Press:

The engaging story of Intellivision, an overlooked videogame system from the late 1970s and early 1980s whose fate was shaped by Mattel, Atari, and countless others who invented the gaming industry. Astrosmash, Snafu, Star Strike, Utopia—do these names sound familiar to you? No? Maybe? They were all videogames created for the Intellivision videogame system, sold by Mattel Electronics between 1979 and 1984. This system was Atari's main rival during a key period when videogames were moving from the arcades into the home. In Intellivision, Tom Boellstorff and Braxton Soderman tell the fascinating inside story of this overlooked gaming system. Along the way, they also analyze Intellivision's chips and code, games, marketing and business strategies, organizational and social history, and the cultural and economic context of the early US games industry from the mid-1970s to the great videogame industry crash of 1983. While many remember Atari, Intellivision has largely been forgotten. As such, Intellivision fills a crucial gap in videogame scholarship, telling the story of a console that sold millions and competed aggressively against Atari. Drawing on a wealth of data from both institutional and personal archives and over 150 interviews with programmers, engineers, executives, marketers, and designers, Boellstorff and Soderman examine the relationship between videogames and toys—an under-analyzed aspect of videogame history—and discuss the impact of home computing on the rise of videogames, the gendered implications of play and videogame design at Mattel, and the blurring of work and play in the early games industry.

Intellivision is a part of the Platform Studies series at the MIT Press edited by Nick Montfort and Ian Bogost, who write in their series forward that "there is also much to be learned from the sustained, intensive, humanistic study of digital media. We believe it is time for humanists to seriously consider the lowest level of computing systems and their relationship to culture and creativity." They describe books of the series as sharing:

- a focus on a single platform or a closely related family of platforms

- technical rigor and in-depth investigation of how computing technologies work

- an awareness of and a discussion of how computing platforms exist in a context of culture and society, being developed on the basis of cultural concepts and then contributing to culture in a variety of ways— for instance, by affecting how people perceive computing.

For our book discussion of Intellivision in this Critical Code Studies Working Group, we will focus on engagement with code and code work. In the book these passages are situated within a broad study of the Intellivision platform and its many historical and cultural contexts. In the opening passages of their introduction ("Introduction: Intelligent Visions": "Blue Skies") the authors frame this situated approach:

We dig into the dirt, so to speak, revealing multifaceted technical and social practices that shaped the platform. We investigate Intellivision’s origins, computational properties, and videogames. We examine its design, advertising, and marketing. We introduce the companies who collaborated to produce it and the people who worked to develop it. We also look outward, reflecting on what Intellivision teaches us about videogames, platform studies, and the social history of technology.

Intellivision’s fascinating story is about a major toy company enter- ing the nascent videogame industry and the wider market for consumer electronics and home computing. It is a story about competing visions for the future of videogames, about the exhilarating and risky experience of exploring uncharted markets, about the intoxicating boom of success and agonizing plummet of failure. It is a story about a videogame system that battled Atari and almost bankrupted Barbie—and along the way, it changed the history of videogames.

Our starting focus for discussion is drawn from Chapters 4-6, and in particular Chapter 5.

- 4 Mattel’s Marketing Magic 107

PART II: Practices- 5 Ladders of Game Production 145

- 6 Becoming a Videogame Programmer at Mattel 167

Linked open access Chapters 4-6, from the Table of Contents.

In this key passage from Chapter 5 (pp150-151), the authors quote APh programmer David Rolfe on the cartridge and EXEC operating system before working through a short code routine from the Intellivision game Major League Baseball written in CP1610 assembly code. The quote and their worked examples explores the relationship between platform-os and software as a relationship between 'body' and 'soul', in a metaphor reminiscent of Cartesian mind-body dualism: "entwined," and yet also "throwing control back and forth":

The EXEC evolved into more than a space-saving device, and game programs on cartridges became deeply entwined with it. “Strictly speaking, the EXEC is like a body without a soul,” Rolfe said. In this metaphor, the cartridge is the soul bringing the EXEC to life, while the EXEC is the body of processes that carry out the soul’s desires. This dance between the EXEC and cartridge code is clear when swinging one’s bat in Major League Baseball. The EXEC handles much of the work, first by calling the BATSWING routine contained on the cartridge ROM:

CMP .UP,R1 ;IS THIS COMMAND FROM UP PLAYER? BNZ RETINS ;IGNORE IT IF NOT MOV #NOKEYDSP,R0 ;PREVENT FURTHER SWINGING MOV R0,.KEYDSP ;BY NOT LISTENING TO KEYPAD ANYMORE CALL S.SWING ;BAT SWING SOUND MOV .BATRUP,R0 ;GET OBJECT NUMBER OF BATTER CALL TOOBJ ;GET DATA BASE ADD #.OBJSEQ,R1 ;WANT TO START SEQUENCINGThis is assembly language code from the Major League Baseball cartridge, with CPU instructions on the left. The text after the semicolons are non-executable comments left by Rolfe to describe what the code is doing. Since this is a two-player game, the BATSWING routine checks to see if the button press came from the player at bat, branching away from the routine if not (BNZ means “branch away if the result of the compare, CMP, is not zero”). The code changes the EXEC’s .KEYDSP variable (the key dispatch) to switch off the keypress interaction on the hand controllers. This prevents you from swinging twice. Then the code triggers the bat swing sound, a process that also uses the EXEC. BATSWING uses another EXEC routine called TOOBJ to retrieve the moving object of the batter and manipulate its animation sequence (using .OBJSEQ, another variable used by the EXEC). This starts the batter’s swinging animation, which is also handled by the EXEC. Then, if the videogame code on the cartridge determines that you hit the ball, the EXEC handles its movement. The EXEC code and the videogame cartridge code are thus constantly throwing control back and forth, like two kids playing catch

Notice that the play logic of the prototypical 20th-century American sport of baseball here is aligned with the logic of the Major League Baseball cartridge for Intellivision, That logic is constituted by e.g. the BATSWING routine and its code snippet, and that the 'soul' of the Baseball player's desire (to swing the bat) is embodied by the Intellivision's EXEC operating system, with Baseball a kind of ur-program or prototypical program against which the constituting logic EXEC against. For the authors co-constitution is actualized during code execution in a way that aligns, once again, with part of the cultural logic of a baseball: "throwing control back and forth, like two kids playing catch."

This suggests many potential entry points into the intellivision and its cartridge, OS, and development code, whether from broad contexts such as business culture or the history and philosophy of sport (and foundations of game studies) or from a single line of CP1610 assembly.

-- Jeremy Douglass, CCSWG 2026

For Discussion:

- What is the relationship of Intellivision code to the role of code in culture?

- How do the EXEC OS and Baseball cartridge and relate to the body/soul concept?

- What is interesting about these code examples and their platform today through the lens of software engineering and computer science, the history of computation, or cultural studies?

- How do the interrelationships of code work across various levels of abstraction (routine, library, operating system, CPU instruction set, hardware...)?

- What are the methodological interrelationships of "platform studies" to "code studies" in these examples?