Howdy, Stranger!

It looks like you're new here. If you want to get involved, click one of these buttons!

Categories

Code/a: a code book coda

- Title: Code/a

- Author/s: Lillian-Yvonne Bertram and Nick Montfort

- Languages: HTML+JavaScript

- Date: ~2024 (publication date)

- Requirements: a web browser with JavaScript support

- DOI: https://doi.org/10.7551/mitpress/15249.003.0017

"Code/a" is a book coda printed in code and appears alongside six example outputs. It is the final piece appearing in Lillian-Yvonne Bertram and Nick Montfort's edited collection Output: An Anthology of Computer-Generated Text, 1953–2023.

The code

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang=”en”>

<head>

<title>Code/a</title>

<!– Code/a copyright (C) 2024 Lillian-Yvonne Bertram & Nick Montfort

Copying and distribution of this file, with or without

modification, are

permitted in any medium without royalty provided the copyright

notice and this

notice are preserved. This file is offered as-is, without any

warranty. –>

</head>

<body>

<div id=coda></div>

<script>

var grammar = {};

const lines = `S~INCREASE UBIQUITY HUMANITY ENCLOSURE RECLAIMING

INCREASE~COMING MORE CGT.

UBIQUITY~It will pervade our CONTEXT.|It will suffuse our CONTEXT.

HUMANITY~Will we be able to distinguish the human-written? HMM

ENCLOSURE~ABOVE will seek, as ever, to SUBDUE access to CGT.

RECLAIMING~We BELOW will ACT computing, reclaiming CGT.

COMING~On its way is|There will be|We'll face|We'll see

MORE~more|much more|a further flood of|an exponential increase in

CONTEXT~media diets|lives|reading|searches|studies|work

HMM~|A continued worry.|Will it matter?|Is this the central question?

ABOVE~Institutions|Mega-corporations|Power complexes|Vectorialists

SUBDUE~SUBDUE and SUBDUE|control|crush|dominate|monopolize|overmaster|own

BELOW~artists|explorers|hackers|innovators|poets|programmers

ACT~ACT and ACT|ACT and ACT|exploit|open up|reinvent|remake|share|subvert

CGT~automated writing|computer-generated text|natural language

generation`;

function expand(token, rest) {

var alternatives, pick, components;

if (Object.hasOwn(grammar, token)) {

alternatives = grammar[token].split('|');

pick = alternatives[~~(Math.random() *

alternatives.length)];

components = pick.split(/\b/);

return expand(components[0],

components.slice(1).concat(rest))

}

return token + ((+rest!=0) ? expand(rest[0], rest.slice(1)) :

'')

}

for (line of lines.split(/\n/)) {

grammar[line.split(/~/)[0]] = line.split(/~/)[1];

}

coda.innerHTML=expand('S', [])

</script>

</body>

</html>

The example outputs

As the only directly authored rather than curated piece in the book, and the only extensive piece of source code per se appearing in the entire book, Code/a represents an exception and an interesting limit case on Output's general editorial philosophy that text generator outputs can, often must, and perhaps should stand on their own unaccompanied by the code that produced them.

Rhetorically, any (or all) of the six example outputs might serve as a final paragraph to the collection -- however, we might choose to read these outputs in the context of the authors' editorial policy from their introduction that "Whenever possible, we used the outputs that natural language researchers and author/programmers themselves presented to showcase their work." This suggests that these six outputs are both a demonstration of the Code/a generator's text possibility space and also to some extent privileged by authorial intent--the final output may have been picked and placed to truly be "the last word":

We'll see a further flood of computer-generated text. It will suffuse our media diets. Will we be able to distinguish the human-written? Is this the central question? Power complexes will seek, as ever, to dominate access to automated writing. We artists will reinvent and remake and share computing, reclaiming natural language generation.

Bounding the code in history

Output is an anthology with examples "1953–2023" -- a clean 70 year span. What would it be like to revisit this Code/a code in 70 years? Would we understand it by its example output, would we need to reimplement it, or could we still execute it? Other than documenting the output or referencing an emulated machine by DOI, what might we say about the code now that would enrich our understanding of it in the future?

JavaScript is a complex set of specifications and a massively parallel set of implementations (particularly browser implementations) that has continuously evolved over the course of the past three decades, just as web browsers themselves have evolved in how they parsed HTML. If we were to revisit this code 70 years from now, we might start by saying that "this code probably ran on a typical 2020s mobile or laptop web browser." With billions of significant cultural objects running in the same code execution environments around the planet, we might also expect our access to emulation to be so robust, and the JavaScript feature set used by this example to be so simple, that this description should more than suffice to get the code up and running.

However, we can probably go further to get a bound on which browsers we would or wouldn't expect this Code/a code to run in -- not just in the future or the present, but in the unevenly distributed past of the web browser. One method is static code analysis -- look at what features of the JavaScript are the least portable. (See a related discussion in this working group on POET in BASIC). In addition to client-side compatibility analysis tools like eslint-plugin-compat, we can manually up per-browser JavaScript keyword support on e.g. CanIUse.com, or we can cut and paste the code into online static analysis such as JavaScript Compatibility Checker. There a generated static analysis focuses on the use of the keyword const, a declaration that affects the variable's scope (block only) and mutability (immutable link). The implementation of the const keyword that vary in complex ways among various browsers over their development lifetime. While at least partially implemented in the vast majority, in some browsers const is not recognized at all, or "is treated like var", or "does not have block scope, or is "only recognized when NOT in strict mode", or is "supported correctly in strict mode, otherwise supported without block scope," et cetera.

Because nothing in the "Code/a" code ever attempts to reassign const lines and nothing attempts to access it outside the scope of the block, there are no practical implications to using const rather than the more common var except that the code will simply run in browsers that recognize const (e.g. Chrome 4+, Firefox 2+, Opera 10+, Safari 3.1+, Edge 12+, IE 11+) and won't run in older browsers that don't (e.g. Opera 9, IE 10). A more complex and up-to-date map of const keyword implementation along with version number timelines and dates appears on CanIUse.com: const. This is a toy example, as in this case choosing almost any browser at random from almost any time within 10 years of the code's publication should work -- however it reminds us that, like pairing printed code snippets such as POET with very specific dialects of BASIC, there often is an intended stack and that stack is partly invisible and needs to be recovered, and with more complex code that uses more obscure features of a language, the stack may be recoverable (and could be initially preserved in the documentation of code critiques) -- if for example a work relied on the "Document picture-in-picture" JS feature released in late 2024 and available on only three specific browsers.

Typesetting pipelines and typographical errors

So, in the future, it would be trivial for us to say "this is how the code is run, and how it ran." But what if the code as we have stored it doesn't run at all, on any browser?

The "Code/a" code is in typeset HTML+JavaScript as it appears in print / ebook editions -- and as the book is print-first in conception, there is no canonical repository on online demo (that I am aware of at this time). This is important in the context of the overall project of the Output book and the Hardcopy book series to bring together computational culture and book arts. It also creates a gap between the typeset text and code execution through the potential for a collection of small typographical errors that must then be corrected -- if an OCR image is taken of the page to extract the text or if an ebook edition is copied / transformed / saved (e.g. between PDF / epub / mobi formats). Any of these paths creates the possibility for a very common publishing pipeline problem in which digital typescript text is prettified for prose printing, automatically detecting and replacing typed characters such as hyphens and apostrophe pairs with en-dashes, right quotes, and left-quotes ("smart quotes").

When formatted like prose for print, the code becomes invalid and will not run in any JavaScript-enabled web browser. The entry point to the generator expand('S', []) may have the pair of apostrophes changed to left-quote and right-quote (smart quotes), resulting in the invalid expand(‘S’, []) and causing the browser to print a blank page and throw the error Uncaught SyntaxError: Invalid or unexpected token. Or the valid page opening HTML comment with two hyphens <!-- may be changed to an invalid en-dash <!–. This means that a canonical, executable version of the code -- e.g. a .html file encoded in UTF-8 test, with all appropriate code characters rather than typographical characters -- is a paratext that we need to create as a first step to running and experimenting with the code.

Minification

Once we have Code/a running, we get a minimal HTML page with a single unformatted paragraph of text that changes each time the page reloads. This newly created output is a secondary paratext, two steps removed from Code/a on the book page. However, Code/a is written to help us easily imagine the simplicity of this page even before we render it. From the code comment to the indented formatting to the meaningful function and variable names (to the fact that it is printed in a book), the "Code/a" code is written in a way that is meant to be read. It performs best practices like clarity, safety, and validity in several ways -- including declaring immutable block scope (const) around the line data that should never be changed, but also in simply parsing correctly as a full, valid HTML page. This is not strictly necessary in order for the output to be rendered in most contemporary and historical web browsers, which are perfectly happy to render HTML fragments such as a <div> and a bit of JavaScript.

If we dispensed with most readability, formatting, validity requirements and simply created a minified code version that functionally produced the same Code/a outputs from the same inputs, it might like something like this:

<div id=coda></div><script>g={};L=`S~INCREASE UBIQUITY HUMANITY ENCLOSURE RECLAIMING/INCREASE~COMING MORE CGT./UBIQUITY~It will pervade our CONTEXT.|It will suffuse our CONTEXT./HUMANITY~Will we be able to distinguish the human-written? HMM/ENCLOSURE~ABOVE will seek, as ever, to SUBDUE access to CGT./RECLAIMING~We BELOW will ACT computing, reclaiming CGT./COMING~On its way is|There will be|We'll face|We'll see/MORE~more|much more|a further flood of|an exponential increase in/CONTEXT~media diets|lives|reading|searches|studies|work/HMM~|A continued worry.|Will it matter?|Is this the central question?/ABOVE~Institutions|Mega-corporations|Power complexes|Vectorialists/SUBDUE~SUBDUE and SUBDUE|control|crush|dominate|monopolize|overmaster|own/BELOW~artists|explorers|hackers|innovators|poets|programmers/ACT~ACT and ACT|ACT and ACT|exploit|open up|reinvent|remake|share|subvert/CGT~automated writing|computer-generated text|natural language generation`;for(l of L.split`/`){a=l.split`~`;g[a[0]]=a[1]}f=(t,r=[])=>g[t]?(p=g[t].split`|`[~~(Math.random()*g[t].split`|`.length)].split(/\b/),f(p[0],p.slice(1).concat(r))):t+(r[0]?f(r.shift(),r):"");coda.innerHTML=f("S");</script>

This is utilitarian compacting without any particular attempt to obscure the code. Further "code golfing" might perhaps shave down the character count even further, but we have already demonstrated the difference between the printed text, which takes the human as a primary reader, and the execution-identical secondary text, which takes the machine as a primary reader with the human reader as an accidental afterthought.

Extensions and porting: running Code/A in Tracery

Rather than condensing and minifying the Code/a code, we can instead expand and extend it by adding alternative outputs to the same core lines data and grammar parser. For example, we could represent the grammar as a Markdown outline, or we could converting lines into the syntax of another text generator system so that Code/a outputs can be produced on a completely different platform.

The below example converts Code/a adapts the bespoke data+generator into the Tracery syntax by Kate Compton (GalaxyKate). It does this by adding a second <div> and <script> at the bottom of <body> that piggybacks on the existing code.

<h2><a href="https://tracery.io/editor/">Tracery</a></h2>

<div><pre id="tracery"></pre></div>

<script>

(w => {

const esc = s => s.replace(/[.*+?^${}()|[\]\\]/g, "\\$&");

w.export = {

toTracery(g, { start="S", origin="origin" } = {}) {

const keys = Object.keys(g);

const subs = keys.map(k => [new RegExp(`\\b${esc(k)}\\b`, "g"), `#${k}#`]);

const conv = s => subs.reduce((t,[re,r]) => t.replace(re, r), s);

const out = {};

out[origin] = [`#${start}#`];

for (const k of keys) out[k] = String(g[k] ?? "").split("|").map(conv);

return out;

}

};

})(window);

const tracery = window.export.toTracery(grammar, { start: "S" });

document.getElementById("tracery").textContent = JSON.stringify(tracery, null, 2);

</script>

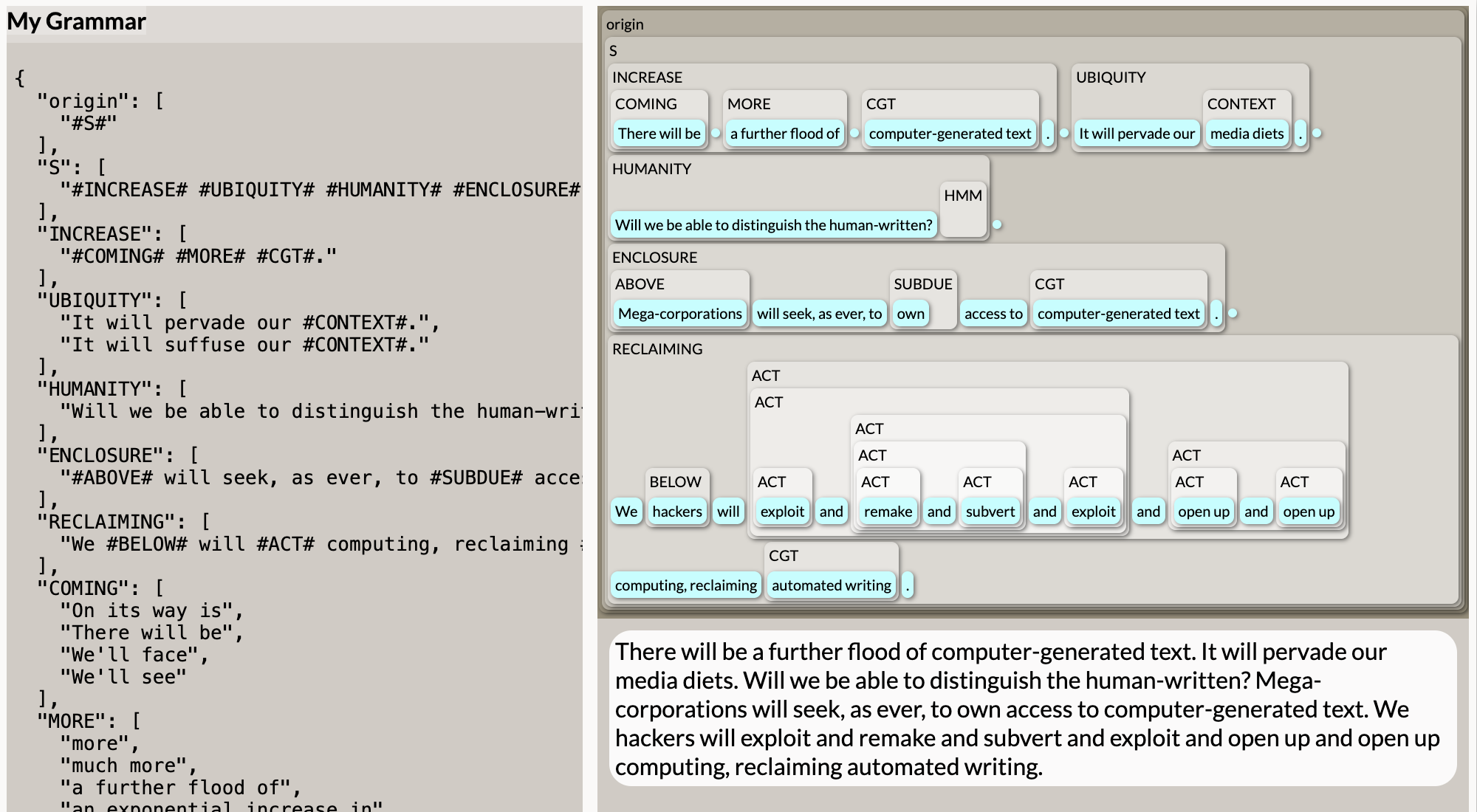

With this addition Tracery output now appears at the bottom of the page, restructuring the grammar parse of the lines into JSON format, this:

{

"origin": [

"#S#"

],

"S": [

"#INCREASE# #UBIQUITY# #HUMANITY# #ENCLOSURE# #RECLAIMING#"

],

"INCREASE": [

"#COMING# #MORE# #CGT#."

],

"UBIQUITY": [

"It will pervade our #CONTEXT#.",

"It will suffuse our #CONTEXT#."

],

...

For example, the original Code/a recursive line:

ACT~ACT and ACT|ACT and ACT|exploit|open up|reinvent|remake|share|subvert

...becomes, in Tracery:

"ACT":["#ACT# and #ACT#", "#ACT# and #ACT#", "exploit", "open up", "reinvent", "remake", "share", "subvert"],

resulting in the full compact Tracery syntax:

{

"origin":["#S#"],

"S":["#INCREASE# #UBIQUITY# #HUMANITY# #ENCLOSURE# #RECLAIMING#"],

"INCREASE":["#COMING# #MORE# #CGT#."],

"UBIQUITY":["It will pervade our #CONTEXT#.", "It will suffuse our #CONTEXT#."],

"HUMANITY":["Will we be able to distinguish the human-written? #HMM#"],

"ENCLOSURE":["#ABOVE# will seek, as ever, to #SUBDUE# access to #CGT#."],

"RECLAIMING":["We #BELOW# will #ACT# computing, reclaiming #CGT#."],

"COMING":["On its way is", "There will be", "We'll face", "We'll see"],

"MORE":["more", "much more", "a further flood of", "an exponential increase in"],

"CONTEXT":["media diets", "lives", "reading", "searches", "studies", "work"],

"HMM":["", "A continued worry.", "Will it matter?", "Is this the central question?"],

"ABOVE":["Institutions", "Mega-corporations", "Power complexes", "Vectorialists"],

"SUBDUE":["#SUBDUE# and #SUBDUE#", "control", "crush", "dominate", "monopolize", "overmaster", "own"],

"BELOW":["artists", "explorers", "hackers", "innovators", "poets", "programmers"],

"ACT":["#ACT# and #ACT#", "#ACT# and #ACT#", "exploit", "open up", "reinvent", "remake", "share", "subvert"],

"CGT":["automated writing", "computer-generated text", "natural language generation"]

}

Equivalent Code/a outputs can then be rendered directly from this syntax by e.g. copying and pasting the Tracery syntax into the Tracery online editor: While this version of Code/a is no longer self-contained, porting it into this larger ecosystem of Tracery tools provides us with access to some built-in advanced features. For example, the Tracery web renderer can display a nested box diagram of each output, tracing how it was generated.

Notice how in this example output illustrates the way that probabilistic recursion in ACT may expand into multiple words (e.g. "We programmers will exploit computing" vs. "We programmers will share and exploit and subvert and reinvent computing"). In addition to illustrating how these recursive trees expand, we can also see artifacts in the logic of a generative model based on random selection. One deeply nested output of recursive ACT clauses results in:

"We hackers will exploit and remake and subvert and exploit and open up and open up computing"

Note in particular the way that "exploit" appears twice in the output above.

The accent of the algorithm: repetition and "stochasticism"

We may hear in repetition the poetic accent of the algorithm--a Markovian voice. In typical writing, words do not recur haphazardly in lists. For a word to appear twice, neither as an immediate repetition for emphasis, nor with a clear secondary meaning, nor to mark part of some larger unit, might seem redundant or perhaps a printer's error. Yet there are a great many forms of repetition commonly described in the history of rhetoric and poetics: direct repetition, anadiplosis, anaphora, antanaclasis, antistasis, diaphora, epistrophe, pesodiplosis, refrain, symploce, or tautophrase, et cetera. Still, none of these describe our second occurrence of "exploit." Instead, we might call this text generator repetition a more pure "stochasticism": highly local probability, unswayed by the attention mechanism which would lead AI large language models (like most humans) suppress it as a highly improbable next token. The six selected outputs of Code/a do testify that direct repetition is possible in the underlying code (e.g. "We hackers will subvert and subvert and subvert and reinvent computing"). Indeed, this may indicate authorial intent to have the output reflect the range of possible text effects, as it is quite unlikely to get even a single ACT verb repetition on six random runs of Code/a, let alone two.

Still, our six examples contain no instances of this more aesthetically contentious disjoint repetition -- which is of course also the authorial and publishing prerogative of selecting one's representative outputs and deciding what it means to represent a generator through its outputs. This tension -- between the chosen output and the larger possibility space of the underlying text generator -- has been a key part of the debate about the artistic merits of text generation for much of the 1953-2023 period that the anthology covers, in which text generators outputs have often been accused of non-representative selection, editing and massaging of outputs, and outright fraud. As the TOPLAP Manifesto says, "Obscurantism is dangerous. Show us your screens" -- and Code/a lets us hold tensions between output and code up to the light and explore them.

What outputs may represent

Just as we extended Code/a with a Tracery generator, we might also extend it with a checker that attempts to map a given output back against the source, confirming that each of the six outputs did (or rather, could), in fact, emerge from this code's possibility space. And, having mapped output text back against code, we might also ask in what ways a set of samples are "representative" of the typical outputs or the range of outputs possible from a generator. Were it not for the use of recursion, most of these calculations would be trivial -- so trivial that we can do them by hand just looking at the code. For example, see the first three lines of the lines data:

const lines = `S~INCREASE UBIQUITY HUMANITY ENCLOSURE RECLAIMING

INCREASE~COMING MORE CGT.

UBIQUITY~It will pervade our CONTEXT.|It will suffuse our CONTEXT.

The start S always includes UBIQUITY, and UBIQUITY will "pervade" our context 50% of the time and "suffuse" it 50% of the time. If we generate 10,000 outputs, indeed ~5,000 of them will contain "pervade." As we continue down the tree, almost every component is in fact a straight probability. For example, S -> ENCLOSURE -> CGT expands to three choices, and CGT (computer-generated text) appears so-called 33% of the time in a way aligned with its canonical token name, or as "automated writing" 33% of the time, or as "natural language" 33% of the time. Rather than CGT being a collection of synonyms, the logic of ENCLOSURE is a parallelism, in which parallel forms of power "seek, as ever, to [SUBDUE] access to" parallel objects.

In some ways Code/a generation is mix and match. Randomly choose one of two UBIQUITY's, of three CGTs, of six CONTEXTs, of three HMM questions, et cetera. Every single token element will be expanded in every single output (S, ABOVE, ACT, BELOW, CGT, COMING, CONTEXT, ENCOLSURE, HMM, HUMANITY, INCREATE, MORE, RECLAIMING, SUBDUE, UBIQUITY). This mostly produces a combinatoric, like a children's split-page book with heads, bodies, and legs on three independently bound stacks of pages. If broken out into poetic lines, most of Code/a could in fact be implemented on strips of paper like [Raymond Queneau's Cent mille milliards de poèmes.

Most, but not all. ACT and SUBDUE are recursive, so e.g. ACT will always be expanded at least once, and probably expanded only once, but may expanded twice, or ten time, or more. It become one verb 75% of the time (6/8); two ~14%, three ~5%, four ~2.5%, five ~1.5%, six ~0.75% and so on.

This means that our worked example output above with six ACT verbs ("We hackers will exploit and remake and subvert and exploit and open up and open up computing") is very atypical of the generator, with outputs of similar ACT length occurring less than 1% of the time. Nevertheless, it is important to remember that, while the typical ACT is one verb, the possible ACT verb count is theoretically unbounded. When I ran Code/a to generate and measure one billion outputs the longest output for ACT expanded to 62 verbs. Indeed, we could add a piece of code to Code/a that simply finds a long output for us each time the page loads. Here is a very simple code snippet that replaces the expand line and accumulates 100,000 iterations, keeping and displaying the longest one.

// coda.innerHTML=expand('S', [])

let longest = "";

for (let i = 0; i < 100000; i++) {

const s = expand("S", []);

if (s.length > longest.length) longest = s;

}

coda.innerHTML = longest;

...and an example output:

We'll see more computer-generated text. It will pervade our lives. Will we be able to distinguish the human-written? A continued worry. Vectorialists will seek, as ever, to control and dominate and dominate and overmaster access to natural language generation. We hackers will open up and share and remake and share and remake and share and open up and exploit and share and open up and exploit and exploit and subvert and open up and share and share and exploit and open up and remake and subvert and remake and exploit and subvert and open up and reinvent computing, reclaiming automated writing.

If we examine the occurrence of simple choices such as e.g. "pervade" vs "suffuse" across the six sample Code/a outputs in Output, it is difficult to draw any conclusion. They might be author selections, or they might be blindly generated by chance. However, it is quite easy to determine example the count of ACT verbs in the examples (1,3,3,2,4,3) and say that they are not at all representative of a typical random sample of generator output (e.g. 1,1,1,2,1,2). Perhaps the authors in arranging their selections really found the recursion appealing, and/or really wanted to demonstrate the range of outputs possible, rather than the most likely outputs possible. The question, in other words, may not be if the outputs are representative or not (the hermeneutics of suspicion question), but instead what they are representative of and how, and why (the hermeneutics of recovery question). In any case, we can say that the printed Code/a outputs have very high recursion for the generator.