Howdy, Stranger!

It looks like you're new here. If you want to get involved, click one of these buttons!

Categories

In this Discussion

Code Critique: "Realitycraft: an RPG Rulesmithing Game"

Title: Realitycraft: an RPG Rulesmithing Game

Author: Samara Hayley Steele

Language: RPG Code / Development Practice

Year/s of development: 2018-2019

About: A number of analog RPGs may be thought of as code that runs on humans. The goal of this project is to create an environment in which players/users co-create analog code and run it.

Software/hardware/wetware requirements:

- Humans. Minimum of 3 players. Works best with around 20. You probably don't want to go much higher than 50.

- Notecards

- Sticky Notes (aka "Post-it Notes")

- Pencils

- (optional) 3-10 black masks. If no black masks are available, matching capes could also work.

- (optional) An hour glass with about 1-2 minutes worth of sand

- Random Objects (for example):

- a drum

- a pair of sunglasses

- a pile of 3-10 ambiguously shaped felt scapes (felt is a type of cloth), preferably large enough to stand on

Warm up (3-5 min):

"Hello everyone! I would like to invite you all to play a rulesmithing game."

Go around the room and give each player 2 sticky notes, 1 notecard, and distribute pencils.

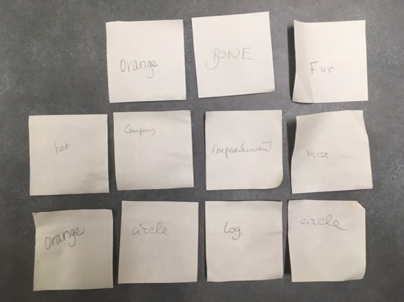

"First I would like you all to write a gender neutral noun on your notecard. It can be any noun, just be sure to pick one that is gender neutral."

Once they have thought up and written down their gender neutral nouns, ask them to write the same noun on one of their sticky notes.

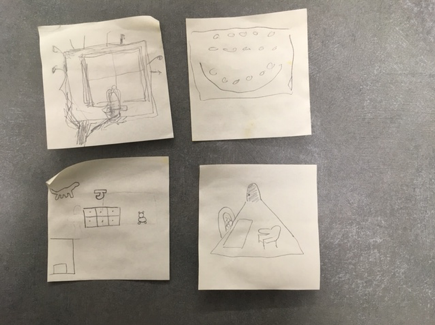

Next, ask them to use their remaining sticky note to draw a room. "It can be any room. Any type of room that you might find in a building. A kitchen or a bathroom or a library or a lobby. Any type of room is okay."

Give them a minute or so to draw their rooms.

Now, ask them to walk around whatever space you are in, and have them place their room somewhere. Some of them might put their room on a wall. Others might put it on a the floor. Everywhere is okay.

Next, ask them all to hand you their notecards. (The notecards should by now each have a gender neutral-noun written on them.)

Now, ask them to place the remaining sticky note (which should have the same noun on it) on their chests.

Rulesmithing (4 min):

Break everyone into 2-3 groups of roughly the same size

Take your Random Objects (for example, a drum, a pair of sunglasses, a pile of felt scrapes) and place them on the ground. Be sure there's about 4 strides of space between each pile.

Assign each group to one of the piles.

"Your job, as a group is to figure out what this thing, or pile of things, does. For example, maybe when I touch this drum, it lets me fly. Or makes me invisible. Or... you get the idea."

Have them work together to figure out what their group's object (or pile) does. Be sure to give them a 1-minute warning to wrap up.

Teaching Each Other the Rules (5 min):

"All right. We're going to teach each other the rules we've just made."

Have each group demo their rule to the rest of the group. Then, have everyone in the group try try the rule out. Make sure they each actually demonstrate that they get the rule. If they don't seem to be getting it, have the others help them.

If a rule seems like it won't get properly distributed, you may choose to step in and modify it. (For example, let's say a group creates a cool rule for a single pair of sunglasses. To make sure that one person doesn't hoard them once the game starts, you can bring out the hourglass and say "A player may only wear the sunglasses for the length of time measured by this hourglass. If you are wearing the sunglasses, be sure to hold hour glass and measure your time. Once the hour glass runs out, you have to put the sunglasses and hour glass on the ground and walk away from them."

Once everyone seems to have a good idea of how the rules/objects work, time to start the RPG (roleplaying game).

The RPG (7-20 min):

"We are going to play a short game, in which we play characters in an alternate universe. Look at the sticky note on your chest: that is your character's name.

"We are in a place called "The Institution." It is a very big place. Remember that room you drew earlier? That room is part of the Institution. And your character is the leading expert about that room."

"In a few minutes, we are going to get into character, and when I call your character's name, it will be their turn to guide everyone to their room and to tell them about it."

"In the mean time, all the rules we have just created with these objects will be in effect. Be sure to help each other if someone has forgotten how the rules work."

"Also, sometimes you'll hear me speak as a voice from the PA system. "testing, testing""

"Everyone, look down at the sticky now on your chest. That is your character's name."

Time to start the game:

"And now we're going to become our characters. Please get into character."

Use your PA voice to start the game. "Welcome to the Instution. Today you will all be giving each other tours of your rooms." Grab a random note card from your pile ad read the name. "[Name] will be offering the first room tour."

As they go, be sure they are using the rules they've created. It's okay if the tour is constantly being interrupted and derailed, as long as they are engaging with the rules they've designed.

Every few minutes, depending on how much time you have, use your "PA system voice" to call upon a new person over to guide everyone to their room and give a tour.

--Optional: Enter the Rule Enforcers (5-10 minutes)--

One they've gotten into a flow of using the rules, pause the game.

Ask: "Who feels pretty confident that you understand how the rules work?" (show of hands)

The first 2-7 hands that go up, give them a black mask.

"Everyone who has a black mask on is now a Rule Enforcer. Your job is to scan the room and make sure that everyone else is following the rules properly."

"Alright everyone, we are going to go back to playing. The next tour should be given by..."

When it is time for the game to end, use your "PA announcer voice" to make some sort of statement. Perhaps, something darkly funny like: "It is now time for the Institution to close. You have all done very well today. Please relocate to your transport methods and vacate the premises or you will be vaporized by security. Repeat: Please relocate to your transport methods and vacate the premises or you will be vaporized by security."

Debrief (5-7 min):

"All right everyone! The game is officially over. I need everyone to help out with clean up!" Remind everyone we are out-of-character now.

Ask everyone to help put the Random objects away and game items away.

Once the space has been restored to its normal/clean form, circle up for a short debrief.

Debrief questions:

- "What was the most interesting moment in the game for you? What was the most fun?"

- "We just created a set of rules and wandered around in a reality in which they are supposedly real. But we all know they aren't real, because we created them together. How did it feel to be in that kind of space? Did the rules ever start to feel real? If so, what made them feel real?"

- (If there were enforcers) "Did the game change once there were enforcers? Was there anything different about that part of the game for you?"

- "Do you think there might be things in the actual so-called "real world" that aren't quite "real" as well? If so, what kinds of things do you suspect might be the result of a set of social agreements?" If you have a whiteboard, write down what they say. Types of things to include: gender, race, nature, the economy. "How are these things so-created? Let's talk through this."

- "What kinds of objects do we treat as if they are these things?" (Examples might include "melanin in a person's skin" "genital configurations" "stock ticker numbers" "plants" "animals")(be sure to ask complicating questions like, "Is your pet dog part of nature? Why not?" or "Is your elbow the thing that gives you gender? Why not?")

- "What kinds of social practices are used to make sure everyone keeps treating these objects that way?"

"Thanks everyone!"

Follow-up writing prompt:

Today we created a set of social rules around a bunch of random objects. But in the "real world," objects are also used as the center pieces for a set of social rules. What's the different between the game we played today, and those social rules in the "real world"? Could we call those real world rules "a game"? Why or why not? What kinds of experiences have you had based on "real world" objects like these? Were they good experiences? Why or why not?

Follow-up reading:

- Dark Matters "Introduction" by Simone Browne

- The New Jim Code by Ruha Benjamin

- Gender Trouble by Judith Bulter

- Take Back the Economy by J.K. Gisbon Graham

- Any RPG rulebook, such as Dungeons and Dragons or something from the White Wolf series.

- "Ideology and Ideological State Apparatuses" by Louis Althusser

- "Reification" from History and Class Consciousness by György Lukács

Artist's Statement

I have now performed “Realitycraft: an RGP Rulesmithing Game” twice, as part of mini-conferences for the UC Davis Performance Studies Department in Dec 2019, and as part of a workshop in late 2018.

My goal with this piece is to simultaneously offer a demonstration of what I call “RPG rulesmithing” or the act of creating intradiegetic objects, while also providing a demonstration of some basic tenants of the RPG medium. With this piece, I also aim to offer a material intervention into the normalization of reified economy, gender, race, and other "non-fiction" diegetic systems that, at times, find themselves congealed into material objects. Rulesmithing, and the adjacent theory of intradiegetic objects, draws upon and modifies certain theoretical investments of Judith Butler, Louis Althusser, J.K. Gibson-Graham, and Gerard Genette.

Rulesmithing, as method, aims to engender fluency in the co-creation of the mutually agreed upon conditions of narrative reality. This mode of fluency I see as liberatory as it allows a re-enchantment of materialities that had previously been subjected to enclosure. This is to say, the ultimate goal of this piece is to facilitate an environment in which participants are engaging in behaviors that might productively be compared to the craft of law, gender, race, and capital while likewise maintaining a focus upon the act of crafting, rather than allowing craft to be invisiblized.

Also, as a feature of this piece, I avoid evoking terms pertaining to specific sets of systematized asymmetrical power relations (capital, gender, race, etc) until the discussion after the piece has been performed. This is because these terms and concepts have been heavily politicized (by virtue of the very asymmetrical power relations that allows their reification to maintains veridicality) and thus may trigger feelings from lived power-relations that, if evoked, may lead participants to foreclose upon engaging with the piece before it begins.

Photographic Documentation (from Nov. 22, 2019 run):

Comments

On November 22, 2019, I held my second run of the above piece, "Realitycraft: An RPG Rulesmithing Game." There were 15 participants/players, and it was held in the auditorium of the Della Davidson Performance Studio in Davis, CA.

One of the basic goals for this piece is to remove 4th wall architecture from a space of narrative performance. This is a basic tenant of any analog RPG game.

Removing the 4th wall is a very different type of move, stylistically and materially, from “breaking the 4th wall.” When the 4th wall is merely “broken,” an actor might walk through the audience, for example, in the musical CATS!, when actors dressed as cats walk through the audience. The power relations of the 4th wall don’t go away when it is “broken” in this way, but rather, the 4th wall power relation is simply flaunted, as diegetically-charged figures move close to and address the audience, while members of the audience have no power to meaningfully transform the diegetic reality.

In the 1990s, I worked for three years as a walk-about performance artist at a medieval village near Seattle, and in this space, audience members would pay handsomely to be able to walk among those of us pretending to be 12th Century English peasants. The power relations were just awful—somewhat like the way “celebrity” is described in Debord’s Society of the Spectacle, insofar as the actor is denied interiority while those you’re performing for are denied a type of exterior meaningfulness within the diegetic reality. This is to say, audience members, in walkabout theatre and also in pieces with 4th wall breakage, are still subject to an authorial/authoritarian model of narrative creation. They don’t get to decide “what happens next in the story,” they are just along for the ride. This leads to a situation in which, as Debord explores, you’re performing for the sake of others: the audience projects a false interiority onto you, imagining you to be some sort of gateway figure into a fantasy world, a fantasy world that you can never quite immerse yourself in because your focus is upon how the audience is “reading you.” This relationship is pretty damaging, I think, for everyone involved, and finding the larp medium in 2003 was incredibly transformative for me, insofar as it is a medium in which narrative power relations are reconfigured to the point that there is no 4th wall.

In my effort to comfortably remove the 4th wall for this piece, I offered number of pre-game tasks through which the participants generated diegetic material that would soon play a role in the interactive narrative. Through these tasks, I was able to gradually ease participants into their roles as co-creators rather than audience members.

I first asked them to write down a gender-neutral noun (without telling them that this would be their character’s name!), and then I asked them to draw a room on a sticky note. It could be any type of room, a library, a kitchen, etc. I then asked them to place the drawings around the auditorium. Next came the rulesmithing.

For the rulesmithing part of the performance (which came before the start of the game), I offered participants three types of objects and asked them to create rules for them. One group was given a drum, another group was given some pieces of green felt, and another group was given a pair of sunglasses. Each group was asked to come up with a rule or a set of rules for their object(s). What does that object do within a fictional reality? What is its “game rule”?

The drum group came up with some movement-based rules evoked each time the drum was played in a certain way. For example, (if my memory serves me) if the drum was beaten once, everyone had to freeze, if it was beaten three times, everyone had to fly. If the wooden edge of the drum was taped, everyone was to cluster under the drum. The sunglasses group decided that wearing the sunglasses made it so you could walk on water, and I added an hourglass timer to this, so that when the hourglass ran out (at 1 min, 45 seconds), you have to give the glasses to someone else.

The group with the green felt bits decided that these objects keep you from falling into water. …the water?

I had nothing to do with the “water.” Water, it seems, is something that emerged in relation to the types of rules that players wanted to create. I didn’t catch whether it was the glasses group or the green felt group that first came up with the idea for water, but I can only assume that one must have influenced the other. While listening into the green felt group, I heard them discussing that they wanted the felt bits to keep them suspended above something—perhaps lava? But then I stepped away to listen in on the drum group, and when I stepped back, they’d decided on water.

Next, it was time to start the game. The players were then informed that the “gender-neutral noun” they wrote down is their character name, and their task (it’s always good to give players a task) was to give each other a tour of the room they had designed. So, the game began. Based on a randomization technique in which I shuffled name cards and drew one, the character named “Impeachment” began to offer a tour of the room that they had drawn. Meanwhile, everyone else dealt with the rules they had just smithed; the various “walking on water” mechanics and the dictates of the drum.

The RPG medium is quite new, just over 4 decades old, and it offers an alternative to traditional narrative media, in which the narrative is delivered authorially, or by a narrative authority. Authorial media are a means through which the oppressed find even the act of creating narratives has been taken from them, and it might be thought of as an ideological form of replicating asymmetrical systems. The RPG medium is a form of aggregate narrative media, and the task of an RPG artist is to decide which parts of the narrative to render aggregate, and which parts should be held authorial. Likewise, at least within a classical larp, the larpmaker(s)' tasks include deciding which parts of the diegesis is deployable and how. For example, in a classical larp, the rulesmith(s) will create a set of codic story elements, along with rules for how to deploy them. They might decide that they want to have “breathing fire” as part of their game, so they might create a “breathing fire rule” in which, for example, a beanbag is used to represent the fire, and in order for a character to “breathe fire,” a person might toss the bean bag in front of them and say “Fire Breath!” This action, is read as breathing fire. This might be compared to the water-based skills that were created as this performance unfolded during the Nov 2019 run, in which, based on the rules that participants smithed, characters were able to walk on water using various methods.

Something I found nice about this particular run is that no one, it seems, was inclined to create rules to represent violence, but rather, the diegesis that emerged was one related to protection—protection from falling into water!—and also modes of slowing down and coming together—as embodied by the drum rules, which froze people, slowed them down, and compelled them to gather, and let them fly.

Thank you for sharing this fascinating writeup.

Is this idea of "rulesmithing" an original coinage, or something that comes out of a particular design tradition? I did a quick scour of some databases and search for "rulesmithing" / "rule-smithing" / "rule smithing" and only found a couple of off-hand mentions in the last three years that could have been independent coinages. [1])https://www.wizardthieffighter.com/2017/37-long-distance-gritty-realism-ii-supplies/) 2

Do you explain or define the term when orienting new groups, or do you let its meaning emerge from the experience?

Trying to think about this practice specifically in the context of critical code studies and software this leads me to some questions:

How are "rules" related to procedures or algorithms? Are these hard rules or fuzzy rules or something else -- and how does that matter?

Are there equivalent digital game genres or other software genres to rule writing games and rule changing games -- I'm thinking specifically of RPG Rulesmithing seen through the lens of traditions like 1000 Blank Cards, or Fluxx.

To what extent does a rulesmithed game leave behind a smithed crafted ruleset or code -- that is, are a set of rules / artifacts captured in some way such that a later group of people could not go through the rule generating phase, but instead simply attempt to play "the same game"? This might defeat the point of the workshop / experience, but I'm also thinking about the question of how it is or might be possible, separate from the question of in what contexts it might be desirable. Could rulesmithing work like a level designer, e.g. LittleBigPlanet / Super Mario Maker et cetera?

As "code that runs on humans" to what extent do you need to specify your platform requirements -- age, language, cultural background, bodily ability, et cetera? I'm thinking about this not just in the sense of a board game box advisory ("Ages 7+") but in terms of helping the community of participants who are rulesmiths create a shared understanding of who they are as players and who they are designing for (even if they are only designing for themselves).