Howdy, Stranger!

It looks like you're new here. If you want to get involved, click one of these buttons!

Categories

In this Discussion

[Code Critique] Unpacking Climate Solutions Data in Code: Using Magic cards to understand the SSPs

"As if we're only mouths to feed..."

—Arcade Fire, Intervention

“Houston, we've had a problem here."

—John Swigert, as the Apollo 13 command module began to fill with carbon dioxide

The goal of this code critique is to work towards an intersectional queer feminist, gameful, and conjunctural approach to climate data while exploring the mechanisms through which the inaccurate, unethical, and derailing "overpopulation" myth has gotten congealed into certain types of climate data, especially the "social" parts of climate scenarios data. The data we are going to look at are used by world leaders to make decisions, and likewise serve as the basis for many climate modeling efforts, games, and software projects.

In regards to the relevance of this "data critique" to code, I hope we can use this example to ask:

- Can the code and the data really be separated? To what degree should those who engage in the critical study of code also engage in the critical study of data that underpin a coding project (see: Kitchin and Lauriault 2014)? To what degree are our critical explorations of code hindered if we do not also "read the data" and explore the data regimes (cf. Buse 2022) that might underpin our coding projects through any data they deploy?

This code critique is also relevant to those engaged in climate gamemaking, and aims to offer a level of transdisciplinary frame alignment (Carley 2019) between thinkers in STEM and the humanities while working with care (cf. Fortun 2024) towards a more ethical approach to "social" climate data parameterization within an increasingly Earth-bound political sphere (Latour 2018).

As part of my critique, I'm going to draw upon the collectable card game Magic: The Gathering (1993-present), as a way to build analogies to unpack the mechanical rhetoric (cf. Bogost 2007) inherent in certain climate data sets, showing how these datasets problematically render human population interactive, thus encouraging users to alter it, while simultaneously inaccurately linking human population numbers to increased emissions.

Rather than merely critiquing, my aim is to think towards reparative making (cf. Sedgwick 1997, Ratto 2007, Currie et al. 2016), and to think through how climate scenarios data might be more ethically and accurately parameterized. In this regard, I have created a GitHub repository for those who would like to try their hand at making alternate, better approaches to parameterizing "social" climate scenarios data—approaches that do not include any metrics that treat human population as being inherently linked to emissions.

Before we start our critical investigation of these data, context is everything—especially when approaching climate data and code (see: Steele 2022, Marino 2020, chapter 4). So, let's start with some context—inflected with some cultural-studies-style conjunctural analysis 😺 (Hall 1988; cf.Grossberg 2019, Gilbert 2019, Gregg 2006).

THE SITUATION

Anthropogenic climate change is real (Frierson 2024, EPA 2023), and its largest contributor is the burning of fossil fuels (EESI 2021, NRDC 2022). Beyond contributing to warming the planet through the greenhouse effect, the burning of fossil fuels contributes to a plethora of other problems for environment and human health, including acidifying the ocean, which is an immediate threat to nearly all marine life (Melzner et al 2020, Doney 2009, Cao & Caldeira 2008, see also: Union of Concerned Scientists 2019), and the release of PM2.5 particulate matter, which is estimated to be responsible for over 3 million deaths a year due to health conditions related to breathing in air pollution (Roser 2021, Tarín-Carrasco 2021, Apte et al. 2015).

Fossil fuels include petroleum (crude oil), gasoline, coal, natural gas, oil shales, bitumen, tar sands, and heavy crude oils (Copp 2024, NRDC 2022). Thanks to the large-scale burning of fossil fuels beginning in the mid-1700s, humans are estimated to have released over 1.5 trillion tons of CO2 into the planet's atmosphere (Friedlingstein et al. 2020, Global Carbon Budget 2023), increasing the amount of this heat-trapping agent in the sky to twice what it was prior to the industrial revolution (NOAA 2022). The "safe" level of 350 ppm (parts per million) of atmospheric CO2 was exceeded in 1988 (Lindsey/NOAA 2023, Hickel 2020).

Flowers are blooming in Antarctica (Singh 2023, Cannone et al. 2022) and a sixth mass extinction is underway, with roughly 1% of species on Earth having been declared extinct and nearly half in decline (Finn et al. 2023), while oceans and mass displacement continue continue to raise. In 2022 alone, over 35 million people were displaced due to extreme weather events (UNHRC 2023), and it is estimated that over 1 billion people will be displaced by 2050 if things continue as they are going (Bellizzi et al. 2023). We are losing our the stability of our climate and the habitability of our oceans as humanitarian crises escalate, and the burning of fossil fuels is largely to blame.

WANT TO FIND A "SOCIAL" CAUSE FOR CLIMATE CHANGE? FOLLOW THE MONEY.

Ending the burning of fossil fuels requires an end to fossil fuel investments and subsidies (Schwanitz et al. 2014, Monasterolo and Raberto 2019). Fossil fuel subsidies are currently being expanded, however, despite calls for them to be phased out (Mcfarlane 2023, Piper 2023), including calls by university students (Bergman 2019), youth activists (Rosen et al. 2016), and Indigenous groups (Horowitz 2023, Moran 2020). In 2023, UN Secretary-General António Guterres called for divestment from fossil fuels and an end to fossil fuel subsidies, as well as immediate global action toward net-zero emissions, which he said “must start with the polluted heart of the climate crisis: the fossil fuel industry” (UN News 2023).

Despite these calls, virtually all major banks and many credit unions continue to invest in expanding fossil fuel extraction (Sierra Club 2023, Roxburgh 2019), despite evidence that divestment from fossil fuels does not show financial risk to investors (Plantinga & Scholtens 2019). If you have a pension or retirement fund, that money is likely being invested in expanding fossil fuel extraction (Climate Safe Pensions 2021, see: FossilFreeFunds.org) for seemingly no reason (ibid).

^ The start screen for Frack, a student-made game that aims to algorithmically track the behavior of fossil fuel extraction companies. This game was designed as part of an experimental course held at ModLab, the Digital Humanities Laboratory at UC Davis, in 2016 taught by Joseph Dumit and Whitney Jane Larrat-Smith (see: Dumit 2017, frackthegame.com).

Steering towards a less catastrophic climate outcome will require the world to cut greenhouse gas emissions, with the IPCC and UN suggesting that emissions be cut by 45% by 2030, and net zero be achieved by 2050 (IPCC AR6 Working Group 2 Report). Yet, due to current investments and subsidies in fossil fuel expansion, global emissions rates are set to increase almost 14% by the end of the 2020s, according to a UN Press release in 2022 (UN News 2022). Since the time of that press release, fossil fuel subsidies and investments have only increased.

In 2023, over $7 trillion in annual subsidies were directed towards expanding fossil fuel infrastructure and extraction, a roughly $2 trillion increase from the year before (Black et al 2023). In this regard, we can assume that the 14% estimated emissions increase is already outdated, as expanded fossil fuel finance is directly linked to expanded burning of fossil fuels (Johnsson et al. 2019, Lazarus & van Asselt 2018, Olson & Lenzmann 2016, see also Klein 2014).

"OVERPOPULATION" IS A MYTH THAT DERAILS EFFORTS TO REIGN IN THE DIRECT CAUSES OF CLIMATE CHANGE—WHILE ACCELERATING OTHER FORMS OF HARM

While discussions about mitigating the climate crisis should be focused on ending fossil fuel extraction—and on ending the subsidies and investments that bankroll it—some rather odd "red herrings" have made their way into conversations about climate solutions, including the flawed idea that the number of people on the planet is too high. The concept of "overpopulation" is a myth (Mosher 2008, Merchant 2021c) that serves to distract attention away from the direct causes of fossil fuel extraction (cf. Merchant 2021a, Merchant 2021b, Alberro 2020), while also being leveraged to accelerate other forms of harm (Sasser 2018, see also: Sasser Interview 2021).

_ by The Anti-Creep Climate Initiative (2022)](https://wg.criticalcodestudies.com/uploads/editor/tf/1d1bdsbqrcxk.png)

^ From Against the Ecofascist Creep by The Anti-Creep Climate Initiative (2022)

The myth of "overpopulation" emerged in the writings of conservative British economist Thomas Malthus in the late 18th century, and the idea was used to normalize the genocide of Irish people a few decades later (Llyod 2007, Gráda 1983, see: Shermer 2015). Starting in the early 1950s, the myth of "overpopulation" experienced a revival in the United States thanks to efforts bankrolled by individuals with fossil fuel interests, as historian Emily Klancher Merchant explores in her award-winning book of history, Building the Population Bomb (Oxford University Press, 2021a, see also: Merchant 2021b, 2022).

Starting in the early 1950s, individuals with fossil interests began funding efforts aimed to manufacture the idea that there was some kind of scientific consensus that "overpopulation" was at fault for various environmental and social problems, when there was never any such consensus (Merchant 2021c, see also: Mosher 2008). As part of this misinformation campaign, white supremacists who openly acknowledged their intention to reduce the number of people of color on the planet, both through forms of forced sterilization and by strategically withholding food, were given powerful platforms (Merchant 2021a, Merchant 2021b).

The myth of "overpopulation" was lobbed into greater public consciousness with the 1968 publication of the book The Population Bomb by Paul and Anne Ehrlich, which leveraged atomic-era hype to drum up unfounded fears around the sheer number of people on the planet (Merchant 2021a; see also: Shermer 2015, Follet 2023). The book became a bestseller, further propping up fossil-fuel-funded misinformation about "overpopulation."

Ultimately, the fears generated by misinformation campaigns promoting the "overpopulation" myth were used to manufacture consent/apathy towards forms of genocide, including forced sterilization directed towards people of color and people in the Global South (Sasser 2018, see also: Shermer 2015) that continue to this day (Mann 2018, Manian 2020, Medosche 2021), while laying the ideological framework to normalize the withholding of food to populations in the Global South (cf. Wittman 2011, Godfrey and Torres 2016). In this way, we might compare the use of the contemporary "overpopulation" myth to the way the concept was used to normalize genocide against Irish people two centuries ago (Llyod 2007, Gráda 1983, see: Shermer 2015), with the myth of "famine" used to normalize withholding food to people whose land has been taken from them through colonial expansion (cf. Burnett & Hay 2023, see also: Grey & Newman 2018).

^ From Against the Ecofascist Creep by The Anti-Creep Climate Initiative (2022)

THE MYTH OF "OVERPOPULATION" REINFORCES CONDITIONS THAT FUEL EMISSIONS

The presence of the myth of "overpopulation" ultimately contributes to the acceleration of emissions and ecological harm. It does this in a number of ways.

For one, the myth of "overpopulation" and its attendant ideology of population control have been used to justify genocide and forced sterilizations of people of color (Sasser 2018, Merchant 2021a), ultimately fueling gender oppressive, colonial, and racist structures. Systemic racism, gender inequity,✝ and colonial land theft have all been found to be drivers of emissions, which is to say, the presence of these harmful social structures leads emissions to go up in ways that can be measured (Steele et. al 2022, Tuana 2023, Lake et al. 2022, ICCA 2021, McGee & Greiner 2020, McGee 2018, Lv and Deng 2019, see also: Thomas 2022). In this way, because the "overpopulation" myth accelerates these social drivers of emissions, the presence of this myth ultimately accelerates emissions.

✝ It is worth keeping in mind that the main reason improved gender equity leads to emissions reduction is not due to access to birth control, but rather due to better policy decisions that occur when decision-making bodies have gender-diverse representation, which is something that requires systemic and pervasive gender equity in order to be achieved (Lake et al 2022, Mavisakalyan & Tarverdi 2019, Liu 2018, Liesher et al. 2016, Lv & Deng 2019, V-Dem 2019).

Additionally, the "overpopulation" myth is (rightly) contentious, and when it is brought up in environmentalist circles, it leads to forms of infighting and coalition breakdown (cf. Sasser 2018, 2021) that ultimately forestall regulation of fossil fuels (Merchant 2021b). In this way, the fossil-fuel-funded "overpopulation" myth might be considered a "union busting" tactic directed towards the environmental movement (cf. McAveley 2020), which is to say, this myth is a tactical intervention that aims to get environmentalists to fight with each other rather than working together to regulate polluters. This is a second way the mere presence of the "overpopulation" myth accelerates emissions (cf. Bogad et al. 2022).

USING ZINES TO DEBUNK THE MYTHS

In an effort to draw attention to types of harmful secondary myths that emerge like hydra heads in response to the continued presence of the "overpopulation" myth in environmental discourse, six scholars affiliated with the Association for the Study of Literature and Environment (ASLE) have joined forces to create the zine Against the Ecofascist Creep (Anson et al 2022, The Anti-Creep Climate Initiative 2022). Using comicbook-style art and dialogue situated within the diegesis of the Marvel Cinematic Universe (MCU), the zine is offered as an educational tool to debunk myths regarding overpopulation that can sometimes crop up in classroom discussions, while offering an intervention into the way these myths have been uncritically reiterated in Marvel films and comics.

^ From Against the Ecofascist Creep by The Anti-Creep Climate Initiative (2022)

MANY CLIMATE MODELS AND DATA FAIL TO MEASURE FOSSIL FUEL INVESTMENT—AND INSTEAD USE BROKEN METRICS TO DIRECT THE FOCUS TOWARDS THE "OVERPOPULATION" MYTH

"There never was a population bomb" (Merchant 2021c). Overpopulation is a myth (Mosher 2008), and yet, thanks to a fossil-fuel-funded misinformation campaign that began in the early 1950s (Marchant 2021a), the broken concept of "overpopulation" has made its way into climate data, models, and educational tools. In this way, the myth of "overpopulation" is now spread is through data sets that inaccurately link raw human population numbers to emissions/pollution.

Data have a type of rhetorical value to them (cf. Currie et al. 2016), and scholars in critical data studies (Kitchin & Lauriault 2014, Iliadis & Russo eds. 2016) and in critical data design (cf. Fortun et al 2016, Reiches & Richardson 2020) have shown how choices made in how data is parameterized ultimately elucidate—or skew—the realities that the data claim to track (Richardson et al. 2018; cf. Poirier 2016).

Environmental data that link human population numbers to emissions in some kind of essentialized way—as if to say human beings are inherently polluting/emitting—are failing to account for a regime designed to necessitate fossil fuel use, and are likewise failing to account for the role of continued fossil fuel investment and subsidies in driving emissions. In this way, these data not only cause forms of harm by advancing the inaccurate "overpopulation" myth, but they fail to accurately track the underlying systemic social cause of emissions: fossil fuel investments and subsidies.

It is worth keeping in mind, though, that these flawed data sets that include "population-as-emissions" metrics have parameterizations that often have been grandfathered in from the era in which people were being inundated with fossil-fuel-funded misinformation about "overpopulation."

WELL-INTENTIONED SOFTWARE PROJECTS AND GAMES SOMETIMES REINFORCE HARMFUL AND INACCURATE MYTHS ABOUT "OVERPOPULATION"—BECAUSE IT'S IN THE DATA

Those who wish to spread awareness about climate change through software and game design often find themselves drawing upon sources of climate data as the basis of interactive features in their games and software without realizing how these data may have been skewed by the inaccurate and unethical myth of "overpopulation." When metrics that (problematically) link population size to emissions numbers are reiterated in software and games, these projects, these things, even if well-intended, ultimately become a hindrance to the climate movement by serving to spread the "overpopulation" myth. Also, even if you don't render population interactive, simply drawing attention to a data set that does can ultimately lead to your work being used to draw attention to and advance this form of misinformation.

ALL THIS IS TO SAY:

As we start looking at this climate data together, it's important to use a critical eye when encountering any data that claim to link population numbers with emissions.

We know now that this linkage is false, and also harmful.

Coming soon:

A Part 2 post with a little more context (And drama! 🙀) before we dive into the data!

Comments

**PART 2: A BIT MORE CONTEXT (AND DRAMA!💅) BEFORE WE GET TO THE DATA **

So, the main cause, or "driver," of climate change is the burning of fossil fuels, and if there is a "social driver" of climate change, it is the continued funding of fossil fuel infrastructure. As we've explored, the number of humans on the planet is not and should not be treated as a driver of climate change (cf. Merchant 2021a, Sasser 2018). Yet, over the last several decades, flawed metrics that treat human population as being inherently linked to emissions have found their way into climate data and models.

Before we start poking around in the data, it's worth taking a little time to ponder some of the cultural practices that are likely to have contributed to the persistence of these flawed "population-as-pollution" metrics. Doing so can help us think about about how we're approaching these data as readers (hermeneutics), while also pondering how we relate to climate science and scientists as subjects within an increasingly Earth-bound political sphere (cf. Latour 2018).

To put it another way: These data have some drama to them; let's get into it! 🍸

ARE SOME SCIENTISTS IN AN ABUSIVE RELATIONSHIP WITH "POPULATION-AS-POLLUTION" METRICS?

—Mike Fortun, Genomics with Care: Minding the Double Binds of Science

—Susan Leigh Star and Geoffrey C. Bowker, Enacting Silence: Residual categories as a challenge for ethics, information systems, and communication

YOU HAVE TO BREAK UP WITH THAT METRIC

Philosopher of science Mike Fortun has offered the analogy of an abusive romantic relationship to explore how data seem to "speak" to scientists in his book, Genomics with Care (Fortun 2024). In his analogy, the data themselves seem to whisper to the scientists, to try and seduce the scientists into accepting data "as is" without questioning the choices made in their parameterization. Fortun is referencing a cultural practice that is common in many scientific communities in which data are treated as if they are inherently "objective and transparent informational entities" (Iliadis & Russo eds. 2016, cf. Bowker 2005, Gitelman ed. 2013). Gently pushing back against this form of fetishism, Fortun urges us to consider that, while data are important, they are incomplete (Fortun 2024, p.18); a deeper understanding needs to be teased out by connecting the data with the things that produced them, something that can be done with the help of "appropriate metadata."

In exploring what he means by "appropriate metadata," Fortun writes:

The process of collecting, articulating, and unpacking the reasoning behind how a given set of data was parameterized—and likewise unpacking the power assemblages that may have impacted its formation—is part of the process of developing reparative metadata, a process through which data can become more useful and reliable (cf. Forune 2024, cf. Kitchin & Lauriault 2014). In this way, we might understand Emily Klancher Merchant's work to unpack the "overpoplution" myth (in Merchant 2021a) as contributing to metadata that can and should be attached to any environmental data that treat population as "pollution."

By taking time to unpack and understand that a moral panic was manufactured around "overpopulation"— a moral panic that led many to the believe (without evidence) that the sheer number of people on the planet was some kind of environmental threat (Merchant 2021a)—we can begin to make sense of how this broken and unethical "population-as-pollution" metric had made its way into so many ecological data sets, and how it was grandfathered into many contemporary climate data sets and models.

Mike Fortun has used the concept of "friendship" as one way of understanding the patterning of relationships with and between scientists (2024). In the case of these flawed metrics that treat population as pollution, we might address the scientists who work with such data as we might a friend who has found themselves in an abusive relationship. You need to get out of this situation, my friend. That "population-as-emissions" metric is doing you no favors. You've got one less problem without it. 💅

RESISTING THE URGE TO GET PARANOID

There are many ways to approach the "reading" of data sets like the ones we're about to look at, including a hermeneutics informed by paranoia. But as queer theorist Eve Sedgwick might remind us: Paranoia is easy. Repair is much harder.

In her 1997 essay, "Paranoid Reading and Reparative Reading: or, You're So Paranoid You Probably Think This Essay is About You," Sedgwick, explores a paranoid hermeneutics that rose to prevalence among literary theorists through the 19th and 20th centuries, and she lends a critical eye to how this way of reading can play out within the context of systemic oppression. Paranoia can be a theft of futurity. As Sedgwick writes:

Queering time, perhaps, takes us out of this lockstep (cf. Freeman 2022)... Reading everything through a paranoid lens, after all, can turn into a type of internalized, intergenerational panopticon (cf. Brown 2015), leading us to operate under the assumption that oppressive structures, regimes, and apparatuses from the past are still there, exactly as they were, which can be wildly limiting. In such a world, we might we might find that rather than haunted houses, it is we ourselves who have become haunted (cf. Castle 1988, Brunton 2023). We bring the ghosts with us when we read nefarious intentions into things that may have actually been well-intended, albeit perhaps fumbled in delivery.

In this spirit, I hope we might reject the urge to indulge in paranoia as we look at these specific sets of climate data, and instead, might do the harder, potentially liberating work of offering the data a reparative reading, thinking towards how such data might be amended.

BUT WHY BOTHER REPAIRING ECOLOGICAL DATA? WHY DOES THIS KIND OF DATA MATTER?

In 2018, philosopher Bruno Latour worked with climate scientist Timothy Lenton to publish an article in Science called "Gaia 2.0: Could Humans Add Some Self Awareness to Earth's Regulating Systems?," in which they suggest transitioning to a politics that better centers the monitoring of the planet's habitability and ecological well-being, writing:

Lenton and Latour also write in favor of "creating an infrastructure of sensors" that would allow "tracking the lag time between environmental changes and reactions of societies," which they see as "the only practical way in which we can hope to add some self-awareness to Gaia’s self-regulation" (2018).

Lenton and Latour are thinking towards an Earth-bound politics in which "sensors" play an increasingly central role in civil discourse, sensors that include ecological data and models that allow us to better track patterns that pertain to the well-being of the ecology, while also looking towards how we might track ways that the social and ecological may be intertwined (see also: Ostrom 2009), Freeman 2021). Such a politics responds to ecological limits (Latour 2018, Stiegler 2020; cf. Green 2020), while engaging with interconnections between ecological and social systems (cf. The Care Collective 2020).

Thinking within this emerging Earth-bound political sphere, we might advocate for ecological data to be as clear, accurate, and ethically parameterized as possible, as such data is increasingly important to public decision-making. In this way, the continued presence of these "population-as-pollution" metrics might be thought of as a smudge on the lens of our public ecological sensors, obscuring and distorting civil discourse.

PERSONAL BACKSTORY

OR: A BIT MORE ON WHY THIS MATTERS TO CODERS, GAMEMAKERS, AND EVERYONE

A couple years back, as part of my work as a Project Director with ModLab, a Digital Humanities laboratory at UC Davis, I organized a series of gamemaking projects for student-researchers. This was part of a larger project to develop what I've come to call educational gamemaking curricula (Steele 2023; cf. Torner 2016, Dumit 2017), through which students engage with topics by making games about them.

One of the topics I was especially interested in incorporating into this student gamemaking research was climate change, as college students these days tend to have a keen interest in the subject. With the guidance of STEM practitioners, I began looking into leading sets of interactive, future-facing climate data, with the goal of putting together a rather holistic toolkit of data sets for students to draw from as they composed their games and code.

Unfortunately, as I began to look more closely into certain climate data sets, I was dismayed to find that virtually all data sets of a certain type had these inaccurate and unethical "population-as-pollution" metrics. Clearly, these data couldn't be part of this project.

A key aspect of the research project was to cultivate a classroom environment that draws upon the methods of the maker movement in education (Martin 2015), methods that include offering a high level of self-direction to students, allowing them get into the "maker mindset," in which teachers take on a less authoritative role, serving as slightly more experienced "co-makers" (Martin 2015; see also: Dumit 2017). In this regard, there was no way I could, in good conscience, hand these data (which were riddled with unethical and inaccurate "population-as-emissions" metrics) over to student-gamemakers—it would have been like handing them a broken tool.

Likewise, If I'd had to lecture to the student-gamemakers on why these metrics are so broken, I would have been stepping into a more performatively authoritative role, which might have disrupted the conditions of the experiment (i.e., encouraging students to stay in a more self-directed "maker mindset"). It's taken the last several years—plus a great deal of soul-searching and guidance from some amazing scholars, activists, and student-researchers—to put together all that I've just shared in this working group post. Without having yet done this work, I simply couldn't see a way to bring such data into a humanities classroom (and honestly, I still can't think of a good way to fit such data into the work we were doing for that project).

I still found ways to set up student gamemaking activities that engaged with climate change as part of the project, but I had to scrap a great deal of material, including a super cool unit in which student-gamemakers would have gotten a chance to try linking game "stats" to real-world ecological sensing tools (cf. Steele 2016b), exercises that already would have been contentious, but that I think could have sparked fruitful conversations at the intersection of politics, ethics, and ecological sensing. This all had to be scraped, of course, once I realized the unethical and inaccurate myth of "overpopulation" was present in the data.

The presence of broken "population-as-pollution" metrics in ecological data can be deeply triggering for students who are part of groups who have been targeted by regimes of genocide normalized by the "overpopulation" myth, including people of color, people from the Global South, Irish people, people with disabilities, and others (cf. Sasser 2018, Gráda 1983, Mosher 2008, Merchant 2021a). No one should ever be put in the position of having to defend the right for members of their demographic to be alive, especially within a classroom environment, and any metrics that promote the "overpopulation" myth through the inclusion of metrics that treat population as "pollution" ultimately lay the groundwork for racist, ablest, and gender-oppressive microaggressions to enter the chat. In this regard, the presence of "population-as-emissions" metrics in climate data can disrupt the ability to uphold a diverse, equitable, and inclusive learning environment, especially in environments that intend to engage deeply and makerly with the data.

Offering my personal backstory as an illustrative example, we begin to see how unethical and inaccurate "population-as-emissions" metrics can interfere with the ability of educators to better incorporate climate data into classroom activities. Likewise, we might also consider how similar issues are likely to arise among others who wish to engage with climate data, such as activists, mediamakers, and policymakers. When unethical myths are congealed into climate data, it becomes far more difficult to bring those data into classrooms, workplaces, and into spaces of public discourse and policy deliberation.

As we consider how the "overpopulation" myth itself accelerates emissions, we might also consider how its presence in climate data parameterization ultimately pushes those data out of many types of social spaces that would otherwise engage with it. In this way, unethical and inaccurate metrics that treat population as "pollution" truly are a smudge on the sensors.

Offering repair to these types of data sets would not only make them more accessible to public discourse in an increasingly Earth-bound political sphere, but also make them more accessible to educators and Digital Humanists who wish to incorporate these types of data into games, media, and software projects.

In the spirit of repair, I've created a GitHub repository where I'm noodling around with ideas for new, more inclusive ways of parameterizing certain types of climate data, including "post-overpopulation" approaches that don't measure population at all. Feel free to hop in if you'd like to tinker! (I suppose if we had good, more inclusive data of this kind, the ecosphere avatar wouldn't have to die at the end of every season of Sivad...)

With all that said, let's finally get into these data!

Stay tuned for PART 3, in which we'll (finally) get into these data—and look towards how Magic: The Gathering might be useful in helping us make sense of them. 🧙♀️

PART 3: LET'S UNPACK THE DATA...USING MAGIC CARDS...?!

Data snippet

(data as it pertains to code)

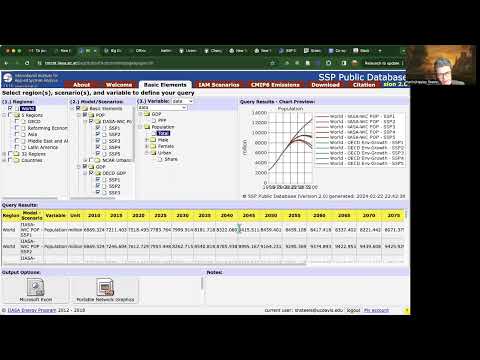

Title: SSP Database - Version 2.0

Author/s: IIASA

Language/s: English

Year/s of development: 2012 - 2018

Software/hardware requirements: A web browser (required)

Available at: https://tntcat.iiasa.ac.at/SspDb (go to the "Basic Elements" tab and click "total population")

Suggested Learning Aid: A Magic: The Gathering deck (self-created), as well as participation in a few games or viewing a tournament

To find the data:

Here's a 3-minute video I made on how to find this data:

THE CLIMATE MODEL AS A MEDIUM

As we wade into the realm of climate modeling, we might look towards the work of philosopher of science Katherine Buse, who has argued that climate models may be thought of as a form of media (Buse 2022a)—a medium that has emerged in relation to cultural expectations primed by the science fiction genre (Buse 2020a, Buse 2022b).

Climate models and data tools mediate our relationships with each other, ecology, and futurity (cf. Buse 2022a). This is why it's important to develop approaches to climate models from within the humanities, including hermeneutics, that we might build more a nuanced and engaged public discourse in relation to these speculative media (cf. Cortiel ed. et al. 2021; Lenton and Latour 2018).

While Dr. Buse offers a more literary hermeneutics of climate modeling, tending to lean more towards exploring aesthetic, affective, and narrative influences that have guided what might be thought of as artistic movements within the climate modeling community, my hermeneutics of the climate model leans more towards conjunctural and rhetorical analyses of models, and their attendant data, code, graphs, "game" mechanics, and assemblages (cf. Hall 1988; cf. Grossberg 2019, Gilbert 2019, Gregg 2006; cf. Currie et al. 2016, Poirier 2019, Bogost 2007, Kitchin and Lauriault 2014). These hermeneutic approaches certainly aren't mutually exclusive and have many points of overlap, but they bring with them different methods, lineages, and ways of knowing that have developed within and in relation to the humanities and cultural studies.

Treating climate models as a medium shouldn't, in any way, be used to question their accuracy. We don't question the accuracy of documentary films simply because they are part of the film medium. In that way, climate models might be compared to documentary films, as far was their relationship to truth-telling goes (cf. Bogad 2022). Would you question the accuracy of a textbook simply by virtue of it being part of the book medium? Understanding something as a medium is simply a way of understanding how it destabilizes and reorients our perception (cf. Jue 2020).

IS IT POSSIBLE TO HAVE A BROKEN METRIC WITHIN AN OTHERWISE ACCURATE MODEL?

Throughout this critique, I've been using the term "inaccurate" to discuss "population-as-emissions" metrics, but I feel a point of clarification is needed about what I mean by "inaccurate."

Over the last five decades, climate models have shown a great deal of accuracy in predicting the warming of the planet (cf. Hausfather et al. 2020, see also: NASA 2020, Carbon Brief 2017). Likewise, fossil fuel companies have spent a great deal of money trying to discredit climate projections (Conway and Oreskes 2010), and when discrediting those projections hasn't worked, they have turned towards cultivating a doomful sense of resignation about the climate (cf. Solnit 2020, Ray 2020)—a sense of resignation that is exacerbated when the fossil-fuel-funded myth of "overpopulation" rears its ugly head, leading those who have managed to stay engaged to experience communication breakdowns (cf. Merchant 2021a, Merchant 2021b Sasser 2018).

The thing I am aiming to critique here is not the geophysics of climate models, but rather the treatment of human population numbers as a "driver," or cause, of emissions.

To understand how a broken metric might find its way into an otherwise accurate model, let's consider this parable:

We can easily see the flawed logic at play here, and might even laugh at the poor denizens of this alternative reality for even considering preemptive toe removal as a legitimate solution for the frostbite crisis. I wonder, though, if they would laugh at us?

Anxiety over the sheer number of people on the planet is a learned behavior, and is largely a U.S. American thing (Merchant 2021a). We have been taught for decades to engage in a flawed, myopic analysis in which we blame people for being trapped in fossil fuel infrastructure while ignoring the ways the benefactors of that infrastructure actively suppresses alternatives (Kaufman 2023, Blewstein et al. 2021). This type of false causality is able to go unchecked due to forms of "math negativity," or math aversion that undermine ways we might better catch flaws in models like this (cf. Finkle 2014, Stodolsky 2010, Vidić et al 2022), and contribute to forms of tactical apora (Carley 2019) that thwart the building of robust coalitions necessary for any successful social movement.

Human beings are not inherently polluting (Farnham 2020; cf. Klein 2014, Graeber and Wengrow 2023); specific ways of organizing industry are warming the planet (cf. Reed 2017; cf. Oxfam 2023). Likewise, when people have more equitable and democratic control over their land, work, and time, emissions go down (cf. Steele et. al 2022, Tuana 2023, Lake et al. 2022, ICCA 2021, McGee 2018, Lv & Deng 2019). It is possible to create a 100% renewable grid (Frierson 2022), but doing so means completely phasing out the investments in and subsidies of fossil fuels (Schwanitz et al. 2014, Plantinga & Scholtens 2019).

ABOUT THE SSPs

By now you should have an idea of why metrics that treat "population-as-pollution" are super broken, and need to be yeeted from ecological data. Unfortunately, this type of metric is present in the SSP data.

If you followed the instructions above, this is what you should be looking at:

These data, the SSP data, are integrated into certain tools and reports that the IPCC, global leaders, and others use to make decisions that pertain to climate. If you're interested, I go into more detail on the assemblages that the SSPs are entangled with in my CCSWG post from two years ago.

Specifically, the SSP data make up a set of "scenarios" that are called the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs). There after five major scenarios in the SSPs. They are named "SSP1," "SSP2, "SSP3," "SSP4," and "SSP5." SSP1 is more or less considered "the good future" and SSP5 is more or less considered "the bad future." (They actually have a little more flavor than that, but as any Magic: The Gathering player knows, there's a rather big difference between flavor text and mechanics...)

The five main SSP scenarios are presented as data-backed stories about the future, and according to a paper by the creators of the SSPs, "the SSPs describe alternative evolutions of future society in the absence of climate change or climate policy" (O'Niell et al 2016). The SSPs are treated as baseline social scenarios that, using interactive models, you can mediate using policy and energy changes, but are also often looked at on their own, such as in this interactive graph which can be found on the Carbon Brief website:

^ Source: Carbon Brief 2019

While the above graph, which plots the SSP data, doesn't appear to include population metrics, that's because each line on the graph is a different "scenario," the metrics are definitely there, but in a way that can be difficult to identify unless you're aware of the metrics that make up each scenario. It's through a type of interplay between the scenarios that the implied interactivity of a tacit population metric becomes apparent.

USING MAGIC: THE GATHERING TO HELP US BETTER UNDERSTAND HOW "POPULATION" IS RENDERED INTERACTIVE IN THE SSPs

In 2007, Ian Bogost argued that game mechanics have a rhetoric to them and that a game mechanic is always ever a type of argument (Bogost 2007, cf. Torner 2018). Since that time, a number of scholars in the humanities have explored how understanding games and game mechanics can help us better make sense of and intervene in power structures in our everyday lives (Jagoda 2020, Bloom 2018, Milburn 2018, Suter et. al 2021).

As an aid to understanding the format and "mechanics" of the SSPs, I find the collectable card game, Magic: The Gathering (MtG) to be quite useful. This same analysis could probably also be done with other Trading Card Games (TCGs), but I like drawing upon MtG for a number of reasons, including its literary and cultural significance. Paul A. Crutcher has argued that Magic: the Gathering is a literary game (2017), and since its creation in 1993, MtG has grown to an estimated 35 million players (cf. Magruder 2022), making it the most commonly played TCG on the planet. This allows us to not only make analogies using MtG game mechanics, but also make cultural comparisons because discourse about MtG play-styles is simply more prevalent due to the game's popularity.

At this time, there are around 27,000 MtG cards or "Magic cards." Prior to playing MtG, you must build a deck that has at least 60 cards, and MtG players tend to spend more time building decks than playing, as a great deal of consideration must go into which cards you select for your deck, as some cards work quite well together, while others don't. To aid players in this deliberative process, each Magic card contains a great deal of information.

There are several types of cards, including Lands, Creatures, Artifacts, Enchantments, etc, which all can play a different type of function in the game.

Let's look at a Creature card:

Image Source: Popular Mechanics

On a given Creature card, there are mechanics (mana cost, abilities, power/toughness) which represent specific congealed power relations within the context of gameplay, and there are also aesthetic/ideological things (the artwork and favor text), which help the player get into character and imagine themselves into a Tolkien-esque fantasy battle while they are playing. Each card also includes a great deal of information that pertains to considerations outside of gameplay, such as if you plan on trading or selling a card, or building a deck with it (i.e., the rarity of the card, the artist's name, the set it's part of, etc).

Let's imagine now that each of the five main scenarios of the SSPs is like a Creature card in MtG: each scenario has a great deal of information attached to it, and also mechanics, but those things are rendered static. Just like you can't change the mana cost, artwork, or rarity of a Magic card, each of the five main SSP scenarios in the SSPs has a bundle of pre-determined settings, information, and even "artwork and flavor text" that is attached to them.

The first thing most people see when they look at the SSPs are what might be called their their "artwork and flavor text": the visuals and narratives that are often packaged with/as the SSPs.

Often, when the SSPs are presented to world-leaders and the public, it is through a line graph that has a line or region that corresponds to each scenario. Such graphs tend to look more or less like this:

^ Image source: UNFCCC

The Y-axis number pertains to CO2 output, and you can see here how these scenarios get tied to different emissions outcomes in visuals like these. Likewise, while you might see different variations of these graphs, this basic way of formatting them is consistent: with each scenario being connected to an emissions outcome, or a range of outcomes, with the SSP5 always tried to the most catastrophic emissions trajectory, while the SSP1 is tied to the most positive emissions outcome.

Here are the labels that are usually given to the five main SSP scenarios:

This graph is usually packaged with a set of standardized "narratives" that have been created to go with the five scenarios. The SSP narratives, and the rationale for them, can be found in this journal article here.

Here's an image of the five standardized SSP narratives:

^ Image from Carbon Brief, original narratives and rationale can be found at Riahi et al. 2017.

Even just looking at the SSPs in this superficial form (the line graph plus the standardized narratives) we might already start to notice a troubled rhetoric of "population" showing up in the narratives in ways that imply that population is linked to the lines that represent future emissions. Additionally, even though the SSPs are coupled with data that pertain to energy transitions, energy changes are rhetorically de-emphasized in in the SSP narratives through the use of jargonistic terms such as "energy intensity" or "energy security" which cannot be deciphered by an ordinary reader. Meanwhile, the (inaccurate) "population" driver is rhetorically emphasized in the narratives through the use of ordinary language.

So, the line graphs and the narratives might be thought of as the "flavor text" and artwork for the SSPs. They set the mood. But to those who "play the game," they are going to be thinking about the mechanics: the metrics that are toggled up or down with in the data in the SSP data that are then linked to emissions changes.

This is where our comparison to a Creature card starts to break down. Yes, each of the main SSP scenarios might be compared to an MtG Creature card, each SSP scenario is also extended through time. Imagine if each creature card came with a set of predetermined "moves" that dictated what happens in the next 10 rounds of gameplay. Each SSP is like that. Each SSP represents a predetermined pathway, with the present moment as the point of divergence between them. This is to say, within the future-facing scenarios organized by these data, there is only one moment in which "players" have the ability to change the pathway: the present.

In this way, rather than being thought of as individual cards, the scenarios instead are more like tools for developing tactics (cf. Carley 2019). Like the final ghost that shows up for Scourge in the Dickens tale, that scenarios offer visions of what could be, with the intention of inspiring change. Also, once you get below the surface of the SSPs, you find these alternative visions of the future are connected to data, data that pertain to and are mediated by various metrics, including population size.

In the SSP database, take a glance down at the data in the spreadsheet near the bottom of the screen.

This part:

Let's zoom in a little:

Basic things to look at:

One interesting thing to notice is that even though, in these data, population is (problematically) linked to more emissions, in some of the scenarios, lower emissions seems like it is associated with higher population. The reason for this is because there are other metrics at play in each scenario, and those metrics might be being toggled up or down in ways that also impact the emissions number in a given scenario.

Within the SSPs, there are three interrelated "social" metrics that are treated as drivers of emissions: "population," "GDP," and "urbanization" (or how many people live in cities). These other "social" metrics also deserve to be critically examined more extensively.

The important thing to keep in mind right now is just that that these other two social factors are also treated as interactive in these models, so, if population goes down when emissions go up, it means that other factors, including perhaps these two factors have been toggled up.

Here is an image that shows how these 3 social metrics are treated in the five main SSP scenarios:

(Image source: Raihi et. al 2016)

Just as those who are fluent in MtG mechanics can see how certain metrics have been toggled up or down in each card, those who are fluent in SSP data will likewise be able to interpret how the three "social drivers" have been toggled differently in each of the SSP scenarios, which, like MtG Creature cards, might be thought of as having congealed "settings" within a range of interconnected mechanics. Likewise, within each SSP scenario, multiple metrics are congealed and presented in a static way (a scenario). The population metric is toggled either up or down in each scenario, alongside other metrics that might also be toggled up or down. Anyone with fluency in this type of data will be able to discern that, in some of the SSP scenarios, population has been toggled up, and in others, population has been toggled down, and that doing so is linked to changes in emissions, with more population always contributing to more emissions, even if emissions might be reduced by other things being toggled down.

The problem, as we know, is that this way of treating population-as-emissions is incorrect and unethical.

Likewise, among these social metrics, there is nothing measuring the investment and subsidences going towards fossil fuel infrastructure, a direct social cause of emissions.

In this way, the mechanical rhetoric inherent in the interactivity of the SSP data set encourages users to strategize reducing population size, which as we know won't work, is unethical, and ultimately will actually increase emissions through the advancement of systemic forms of oppression inherent in any efforts to control population size.

Likewise, these data offer mechanical rhetoric regarding a social practice that would actually reduce emissions: changing the amount of funds directed towards fossil fuel continence and expansion.

We might imagine that, just as different MtG players approach building a deck very differently (see: Rosewater 2015, Rosewater 2013), within communities that engage with the SSP data, different individuals and groups might develop different strategies based upon the things implied by the data within a "game" in which the "win" situation is avoiding the worst impacts of climate change.

As we've seen, the SSPs incorrectly link at least one social metric to emissions — population. This linkage creates an inaccurate form of mechanical rhetoric through which the reduction of population is treated as a type of boon. In this way, it creates the false image that population reducation is like an MtG Mana card that let you draw more Mana reach turn. Like this Swamp card:

Having such a card in play increases your Mana Pool at the start of each turn, so it's a card that makes things generally more amiable to "win" scenario in a way that benefits you in each round. Worth remembering: the population metric is actually calibrated wrong, so in reality, there is no such boon, but the presence of this metric encourages the adoption of strategies that aim to reduce the number of people on the planet, despite the factual and ethical issues of such approaches.

It's worth emphasizing that the unethical and inaccurate approach of reducing population is just one of many "tactics" implied by the procedural rhetoric of the SSPs. In this way, some who are using these data to make decisions might ignore the population metrics, just as someone building a Simic deck (mountain/forest) might entirely ignore swamp cards. But because the mechanical rhetoric of population reduction being treated as a boon exists (inaccurately) within the scenarios data, population will be encouraged as a tactic.

I recall in the late 2000s, a new type of MtG mechanic was introduced called "Dredge" was introduced that allowed players to revive cards from their Graveyard. I knew some MtG players around that time who were absolutely disgusted by this new mechanic, and who were appalled to see that some people had started to build entire decks around the use of this mechanic, a deck type now known as "dredge decks."

Any time a mechanic is present in a game, there will be players out there who use it. When "population" is rendered interactive in climate data, and likewise (inaccurately) linked to emissions numbers, there will be people who treat the interactivity of that mechanic as prescriptive. In this way, we can begin to contemplate the ethical problems inherent in the way "population" is handled in the SSP data base.

HOW THE SSPs MAKE IT INTO SOFTWARE AND CODE

Those who are concerned about climate change might feel motivated to help make climate data more accessible to everyone, with the hope of improving collective decision-making in steering the planet towards the best climate outcome that is still possible. Among the data they might stumble upon while trying to create software, media, and games of this nature are are the SSPs.

Some interactive tools created using SSP data include including the MAGICC interactive interface, and interactive tools created by Carbon Brief. These tools were most likely created from a well-intentioned place, but unfortunately, any work to elevate the SSPs (as they are now) elevate these incorrect and unethical fossil-fuel-funded "overpopulation" metrics, insofar as they are embedded in the data that organize the SSP scenarios.

WHAT IF WE MAKE BETTER CLIMATE SCENARIOS DATA? TOWARDS CRITICAL & REPARATIVE MAKING

In the spirit of critical and reparative making, I've created a GitHub Repository where we might explore new ways to parameterize future-facing climate data. Is it possible to weed out inaccurate and unethical metrics that emerge from myths like "overpopulation" and make future-facing climate data more accurate and ethical? Let's tinker! 🔧👷

I think this is super interesting, and definitely part of a broader discussion of the reification of ontologies through code, which then implicitly orient the discussion space.

I haven't gone through all of your code critique, but the first thing that comes to mind about the unintended humanistic implications of data is that it's already very hard to just figure out the traditional implications of data, especially when they are coming from such complex data sets as climate research. Check this conference presentation by Patrick Ferris for a mismatch of the two approaches: https://undonecs.sciencesconf.org/data/pages/05_02_Patrick_Ferris.pdf

@pierre_d_ For sure! Reification is funny that way. Thanks for sharing this!

I wonder to what degree it’s only hard because we haven’t made it a practice to read data?

I’m thinking now of the book Data Feminism by Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren Klein (2019, MIT Press) which I think does a great job modeling an intersectional feminist approach to reading data.

@HarlinHayleySteele thanks for the reference.

And yes, I would think that a large part is about best-practices. I can't remember who was mentioning the comparison between chemistry and data science: students in chemistry are taught from the beginning to write down all their steps and observations in lab notebooks, to which they can refer to in the future, and there does not seem to be an equivalent in foundational courses in data science (writing down and archiving the URL, writing down the metadata of the data source they're using, etc.?)

CORRECTING AN ERROR

Oh drat! The PART 3 post was locked before I could finish editing it.

Well, I guess the only egregious error in it is this sentence:

It should instead read:

Yeah, ha ha. By leaving "fail to" out of that sentence, it literally says the opposite of what I meant to say! 😅 Whoops! I'm sorry for any confusion that may have caused!

There are quite a few typos in PART 3 and moments of untamed language... but for everything else I think it's possible to read and figure out what I was trying to say... even if some of the half-baked ideas in that could use a bit more time in the oven... 🤷🏻♀️

Oh right!

The "Part 3" post locked before I could add a thing that's super worth considering about MtG culture & play-styles!

STYLES OF PLAY IN MAGIC THE GATHERING... AND IN "WINNING" CLIMATE CHANGE??

Over the years, MtG players have come to acknowledge at least three styles of play or "player types," which have been nicknamed Timmy/Tammy, Johnny/Jenny, and Spike (Rosewater 2015, Rosewater 2013).

(^ I love the implied gender fluidity by having a backslash between some of the names... I am convinced that Timmy/Tammy is one person! Same goes for Johnny/Jenny. ...Spike is obviously an enbie.)

Here's my attempt to summarize what these three play-styles are:

These three main MtG play-styles are enough of a pattern that it's relatively common to hear the terms come up in communities while gossiping about each other's deck-building styles. There is no one superior style of play, as long as you're playing in a way that brings you joy (cf. Boluk and LeMieux 2017, Simkins 2014).

It's worth keeping in mind that lots of folks are hybrid players and don't fit neatly into these categories—sometimes we step into different roles in different times in our lives based on what feels right at the time. Also, it's worth keeping in mind that other styles of MtG engagement have been identified over the years beyond "the big three," including Vorthos and Mel (cf. Parlock 2022).

We might imagine that, just as different MtG players approach building a deck very differently, within communities that engage with the SSP data different individuals and groups might develop different strategies based upon the things implied by the data within a "game" in which the "win" scenario is collectively steering towards the best climate outcome that's still possible.

The SSPs incorrectly link at least one metric to emissions — population size. This linkage creates an inaccurate form of mechanical rhetoric through which the reduction of population is treated as playing a role similar to that Swamp card up there in MtG. This might inspire people to build entire decks around that card... Obviously, this is a very bad thing, a terrifying reality that I think gamers are especially apt to sit with and acknowledge.

Many of us have seen how sometimes someone in our gaming community will engage mechanics in ways that... while falling within the technical bounds of the rules... make the game feel unsafe, uncomfortable, or even break the game. Having a mechanic like "reduce population" inaccurately and unethically treated like a boon within the SSPs created the false impression that population control works (it doesn't), beyond having horrific ethical implications.

This broken "emissions-as-population" metric also exists within many other types of ecological data, it is an invitation for the types of problematic "within the bounds of the rules" behavior that we have seen drive people away from our gaming communities. Perhaps then, as gamers, we can understand the need, more than ever, to offer a level of repair to these types of climate data and remove these "population-as-emissions" metrics from all ecological data.

If you want to try building an alternative "rule set" to the game of fixing climate change - which is to say building up some scenarios that don't treat "population" as a driver, please do hop into this GitHub repository:

Let's see if we can't fix this!

In case you're looking to turn all this into a PBL moment with students, here are some ideas:

IDEAS FOR THINGS TO DO WITH STUDENTS

IF YOU WANT TO MAKE A GAME ABOUT THIS KIND OF THING: