Howdy, Stranger!

It looks like you're new here. If you want to get involved, click one of these buttons!

Categories

In this Discussion

Book: Forty-Four Esolangs by Daniel Temkin

Daniel Temkin's Forty-Four Esolangs: The Art of Esoteric Code is our featured book discussion for this week.

Strands forming a glyph as part of a short program computing the Fibonacci sequence in the esolang Rivulet.

From the MIT Press:

A riveting collection of one artist’s many approaches to esolangs—esoteric programming languages—showcasing the form’s limitless artistic potential. In Forty-Four Esolangs, Daniel Temkin challenges conventional definitions of language, code, and computer, showing the potential of esolangs—or esoteric programming languages—as pure idea art. The languages in this volume ask programmers to write code in the form of prayer to the Greek gods, or as a pattern of empty folders, or to type code in tandem with another programmer, each with one hand on the keyboard, their rhythm and synchrony signifying computer action. Temkin includes languages written over the past fifteen years, along with some designed especially for this book. Other pieces are left as prompts for the reader to simply consider or perhaps to implement on their own. Esolangs are a collaborative form. Each language is a complete world of thought, where esoprogrammers build on the work of esolangers to make new discoveries. The language Velato, for instance, asks programmers to write music as code; while the language creates constraints for the programmer, each programmer brings their own coding and musical sensibility to the language. Other pieces are pure poetic suggestion in the legacy of Yoko Ono’s event scores. These ask the programmer to, for example, follow the paths of the clouds over a single day and construct a language in response that uses those movements as code. Just as Ben Vautier claimed everything is art, this book blurs the lines between computation and everything else.

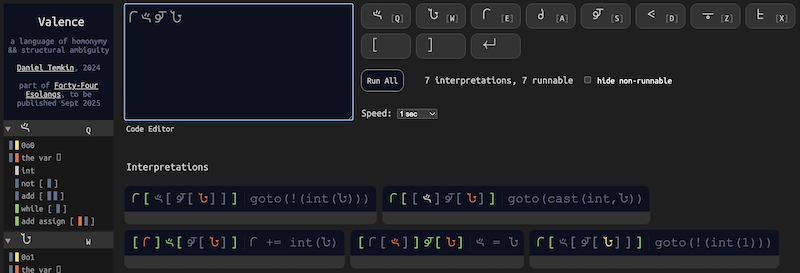

Homonymic symbols encoding a multivalent statement with multiple GOTO interpretations in the esolang Valence.

Forty-Four Esolangs is a part of the Hardcopy series at the MIT Press edited by Nick Montfort and Mary Flanagan. From their series forward:

Hardcopy features computational artworks that manifest themselves in print. Works in the series engage with and arise from computation in culturally important ways. The series is a space for (among other things) books that are computer-generated by artists and poets, whether they include text, image or both; print works based around glitched media formats; ones that feature type-in programs with sample output; and ones arising from online interaction with automated agents.

For this Critical Code Studies Working Group book discussion of Forty-Four Esolangs we may begin with a framing and a common starting point of a few selected passages (provided below). To situate the provided selections it is important to understand the structure of Temkin's book, which draws on Sol LeWitt's distinction between "concept" and "idea" in conceptual art and adapts it to code art practice. Accordingly Forty-Four Esolangs enumerates the presentation of 44 conceptual "Prompts" in the first half of the book (Language 0, Language 1, Language 2...). The book then presents variously-implemented "Realizations" in the book's second half, each named ("Velato (2009)", "Olympus (2022)", "FatFinger (2017)"...) and each corresponding to a numbered Prompt.

This week in our Working Group is organized around the topic "Where is the Critical in Critical Code Studies?" -- and it makes particular sense at this moment for us to unpack the critical heft behind Temkin's works of "pure idea art" in a conceptual art tradition. Forty-Four Esolangs features an excellent forward by Allison Parrish, who frames Temkin's code art practice as aesthetic-political as she draws a line departing from Peter Naur's notion of the programmer's abstract “Theory Building View” through to Lillian-Yvonne Bertram's "Of course, programming is political. How could it not be? No one is doing anything in coding without someone else.” Parish arrives here by way of a key passage from the conclusion of Amy J. Ko's "What is a Programming Language, Really?" (2016):

"[W]e understand what [programming languages (PL)] are formally and we increasingly understand what they are as tools. Other agendas, particularly those that probe the human, social, societal, and ethical dimensions of PL, are hardly explored at all. As researchers, we should be concerned with every view, and see each as an opportunity to understand holistically how PL can shape our world"

Selections from Forty-Four Esolangs are provided here as shared starting points for discussion. The short excerpts include the author's Preface, the manifesto-like "Sentences on Code Art", three conceptual Prompts (4, 40, and 41), and three corresponding Realizations ("Cloud Computing", "Rivulet", "Valence"). The selections are embedded and attached below along with linked resources, including the source code for two realizations, corresponding online interactive editor for each, and some introductory tutorials / documentation. Consider trying out the examples given in the reading selections (or exploring your own creations).

Temkin's work may illuminate (and be illuminated by) LeWitt's conceptual art, Montfort and Flanagan's print computational artworks, Naur's "Theory Building View," Bertam's "programming is political," or Ko's "human, social, societal, and ethical dimensions." However, in the end, we may return to the bare question: What are Temkin's esolangs? What is the art of esoteric code? Thank you for joining this discussion.

-- Jeremy Douglass, CCSWG 2026

For Discussion:

- What is the relationship of esoteric code to code in culture?

- How does esoteric code relate to conceptual art?

- What do these programming languages look like through the lens of software engineering and computer science?

- What do they look like from the point of view of the history of computation?

- How is Forty-Four Esolangs related to the concept of "print computational artwork"?

- How do we see Bertram's "programming is political" or Ko's "human, social, societal, and ethical dimensions" in this work?

Resources:

- Realization 40 (Rivulet) [source code] [online editor] [introduction]

- Realization 41 (Valence) [source code] [online editor] [introduction]

- Chinchilla, Chris. "Esoteric Languages Challenge Coders to Think Way Outside the Box: Daniel Temkin’s new book dives into the coding exercise/art form." IEEE Spectrum, 04 Sep 2025. [Feature author interview]

Forty-Four Esolangs--excerpts (Preface, Sentences on Code Art, Prompts 4,40,41, Realizations 4, 40, 41):

Comments

As regards "What do these programming languages look like through the lens of software engineering and computer science?" I'm pretty much a work-a-day engineer, often computational, but equally often mechanical, chemical, or biological. I am not very artistically-oriented; I like art but I'm definitely not an artist nor art ... connoisseur. Last week, for example, I went 200 miles out of my way to visit the Dali museum in Tampa, and it was fantastic, but a day of direct Dali every 20 years is enough for me. Although I appreciate (in the Dali-like sense, as above) "artistic" engineering, like the Gateway Arch or the Eiffel Tower, what I get emotional about is great USEFUL engineering, like airplanes or Lisp, and when you can combine them, as for example the Golden Gate Bridge, I am literally brought to tears. Given this personal background, my reaction to most esolangs is more like my response to Dali or the Eiffel Tower: That's nice, and kind of a cool engineering hack -- and I really do appreciate the beauty! -- but if no one had bothered, I wouldn't miss it. Whereas, if no one had bothered with airplanes, Lisp, or the GG Bridge I would definitely miss it (in retrospect). I sometimes try to spend time working through an esolang problem, for example the interesting post on ambiguity in Valence, but because these are actual programming languages, and one needs to actually work through them in order to puzzle out the details -- as opposed to just walking through the Dali museum and looking at all the cool melty things and flaming giraffes, or simply taking an elevator up the Eiffel Tower -- I quickly find it not worth the effort to figure out, and move on. This isn't at all to dis those who have the mental space to work through problems in esolangs, but ... well, you didn't quite ask about what esolangs look like through the lens of a specific engineer, but that's the only perspective I can offer, FWIW. (I do often wish that they esolangs used simple alphabets where possible. I used to be quite an active APL programmer -- in fact, I inherited and ran the project that wrote Univac's APL environment! APL, as you may be aware, had a specialized character set, but it needed that because it was specifically (mostly, anyway) a mathematical language, and ... well, math is done with fancy characters, so we're sort of stuck with it. Also, by having built-ins be single characters, it made complex expressions extremely compact -- for better or worse can be argued, and has been ad nauseam! APL was one of those "esolangs" -- although it's not too eso -- that is more like the GG Bridge -- beautiful, obscure (at least these days) but really really useful. In fact, APL in modern form -- with actual words, is still used in the financial industry in the guise of a language called "K".)

I love to see this reflection on technological art @jshrager and appreciate this report of an engineer's eye on art. I wonder if rather than trying to learn the esolang as you might a programming language that we need to use to build something (as an engineer builds a bridge) perhaps it would be more useful to see an esolang -- particularly @DanielTemkin 's esolangs collected in his book -- as a provocation.

For example, in the case of Valence, what would it mean for tokens in programming languages to have multi-valent rather than ambiguous effects? Or what thoughts and feelings does a programming language stir in which the programmer must plead with and interpreter-god with every line they write? I guess the question is not so much how do you esteem these languages as what thoughts do they inspire?