Howdy, Stranger!

It looks like you're new here. If you want to get involved, click one of these buttons!

Categories

In this Discussion

Scribe: A Document Specification Language (1980)

Author: Brian K. Reid

Language: The Scribe markup language itself; compiler implemented in BLISS-10 for PDP-10 systems

Year: 1980

Source: Reid's PhD dissertation, Carnegie Mellon University (CMU-CS-81-100)

Software/Hardware Requirements

The original Scribe compiler ran on PDP-10 systems under TOPS-10 and TOPS-20 operating systems. The compiler was written in BLISS (See BLISS Guide and BLISS history), Digital Equipment Corporation's systems programming language. Users authored manuscript files (typically using a ".MSS" extension) in any text editor, then processed them through the Scribe compiler to generate formatted output. A database of format specifications, prepared separately by graphic designers, controlled presentation. The system was later commercialised by Unilogic (renamed Scribe Systems) and ported to VAX/VMS.

Context

This code critique accompanies the forthcoming Markdown code critique in Week 2. Scribe occupies a key position in this history as the first system to achieve what Reid called "a clean separation of presentation and content." The dissertation presents both the markup language specification and its compiler implementation, making it an interesting object for critical code study.

Scribe matters for three reasons. (1) its architectural decisions about separating logical structure from physical presentation directly influenced LaTeX, HTML, and CSS. (2) its commercialisation history became a formative event in the emergence of the free software movement, with Richard Stallman citing it as a betrayal of hacker ethics (!). (3) Reid's dissertation represents a moment when document preparation was thought about as a problem of knowledge representation and compiler design, not merely a practical tool.

Code

The Scribe Manuscript Language

Scribe manuscripts are plain text files with embedded @ commands. The @ symbol introduced all markup, followed by either a direct command with parenthetical content or a Begin-End block for extended passages. For example,

@Heading(The Beginning)

@Begin(Quotation)

Let's start at the very beginning, a very good place to start

@End(Quotation)

Commands could take named parameters, enabling structured metadata, such as,

@MakeSection(tag=beginning, title="The Beginning")

The syntax also permitted flexible delimiters. Where parentheses might cause problems or conflict with content, authors could substitute brackets, braces, or angle brackets, as shown in this example,

@i[italic text with (parentheses) inside]

@b{bold text}

@code<some code>

This flexibility around the delimiter was a design principle that ran through Scribe and which can be said to accommodate human writers rather than optimising for machine parsing of the documents (rather like markdown today!).

Document Structure and Compilation

Large documents composed chapters from separate files, referenced by a master document, such as,

@make(report)

@style(paperwidth 8.5 inches, paperlength 9.5 inches)

@style(leftmargin 1.0 inches, rightmargin 1.0 inches)

@include(chapter1.mss)

@include(chapter2.mss)

@include(chapter3.mss)

The master file declared the styles and macros. From concatenated sources, the compiler then computed the chapter numbers, page numbers, and cross-references automatically.

Bibliographic Database

Scribe also supported structured bibliographic entries that anticipated later systems, such as Zotero,

The Scribe compiler contains a simple special-purpose database retrieval mechanism built to be a test bed for the more general task of generalized database retrieval from within a formatting compiler. Briefly, the author in preparing a manuscript makes citations to various bibliographic entries that he knows are stored in a bibliographic data base. The compiler collects the text of the bibliographic references, sorts them into an appropriate order, formats them into an appropriate format, and includes the resulting table in an appropriate place in the document (Reid 1980: 80).

@techreport(PUB,

key="Tesler",

author="Tesler, Larry",

title="PUB: The Document Compiler",

institution="Stanford AI Laboratory",

year="1972")

@book(Volume3,

key="Knuth",

author="Knuth, Donald E.",

title="Sorting and Searching",

publisher="Addison-Wesley",

year="1973")

These entries are stored in Scribe's database which could then be cited by "key" within manuscripts, with the system generating formatted bibliographies according to chosen style specifications.

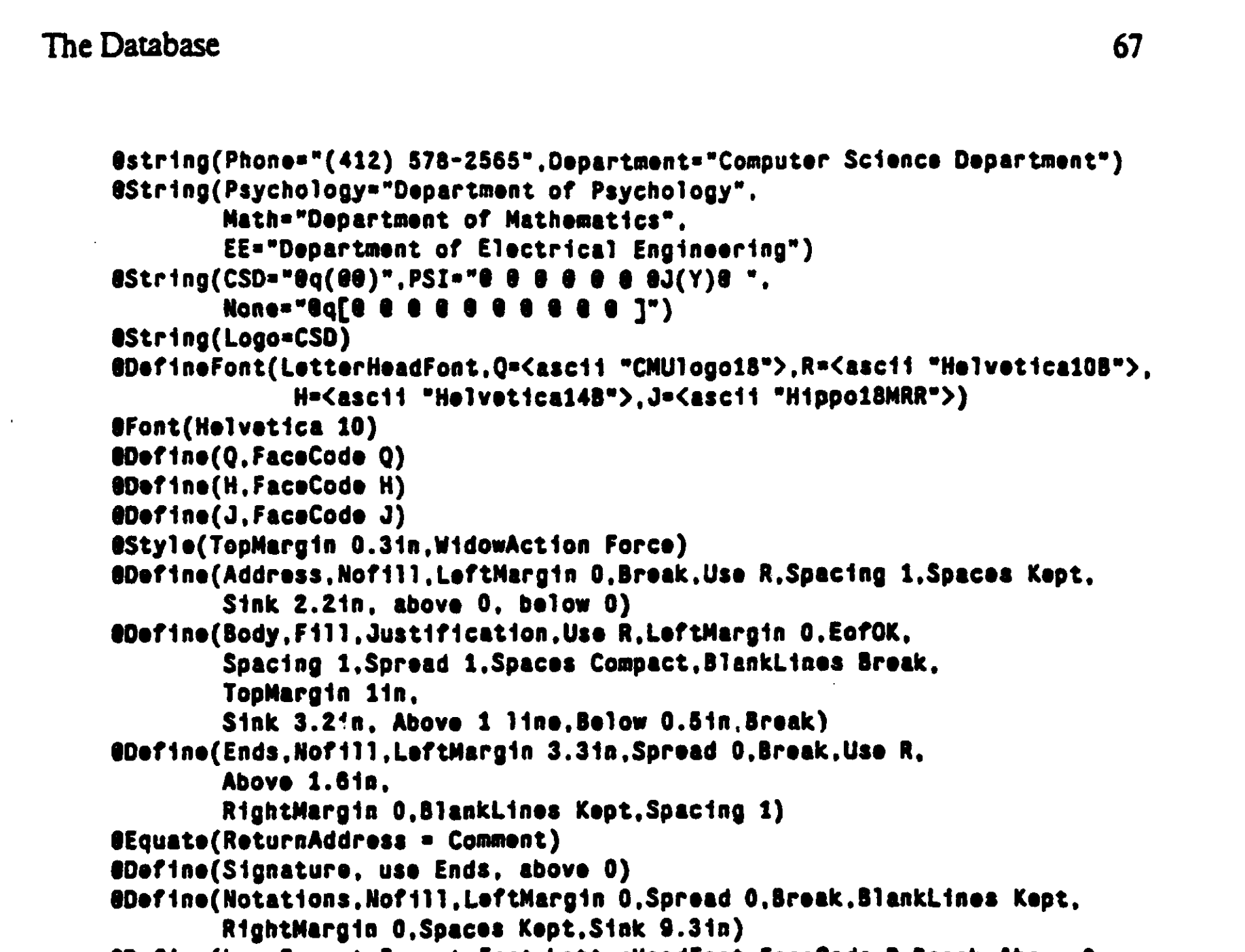

Architecture

Reid's dissertation describes the compiler's architecture in terms that is similar to contemporary software. The "approximately one hundred independent variables" controlling formatting were organised into a database that functioned like what we would now call a configuration layer or CSS stylesheet. Document types (report, article, book) were defined by different variable configurations rather than different code paths.

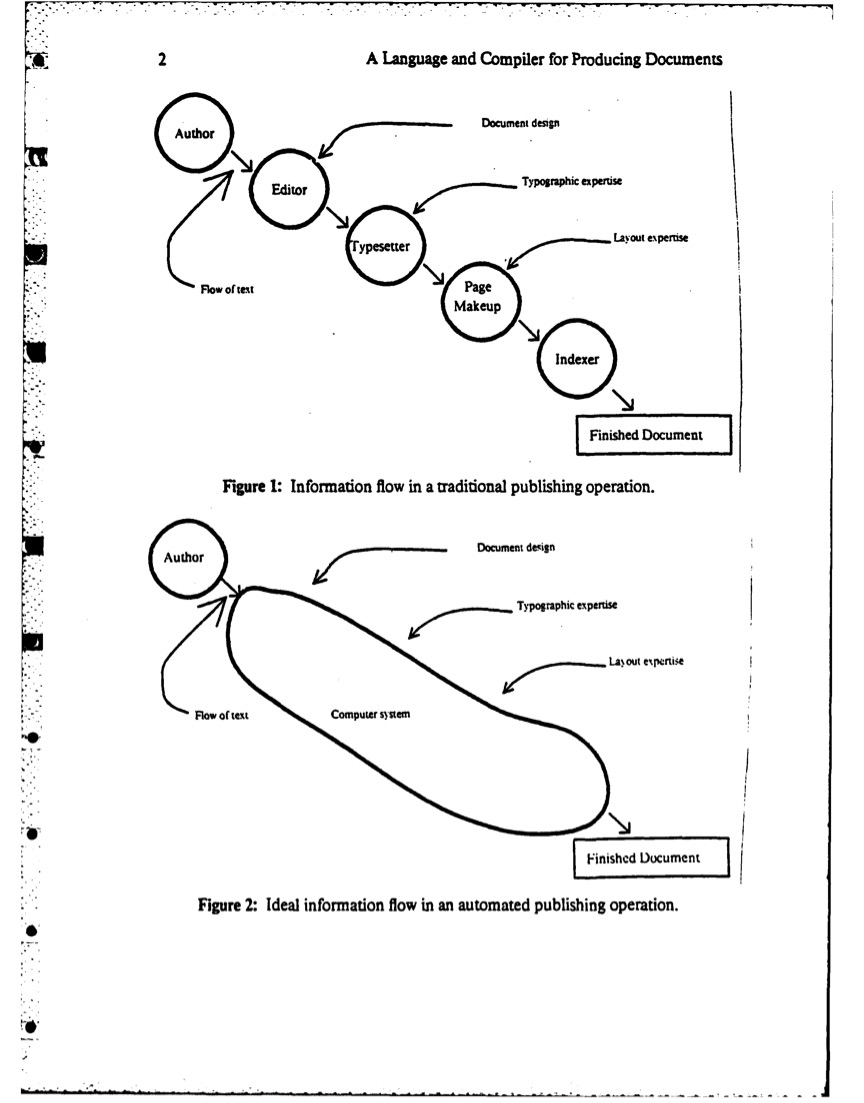

The compiler parsed manuscripts into an intermediate representation, applied format specifications from the database, and generated device-specific output. This "pipeline" architecture, separating parsing from formatting from rendering, established patterns that persist in contemporary document systems.

Provocations for Discussion

On the @ syntax, Douglas Crockford has argued that retaining Scribe's syntax for web markup might have prevented problems later caused by SGML and XML adoption. The @ symbol with flexible delimiters was "significantly easier to write in" than angle-bracket markup. Why did angle brackets win? Was this a technical decision or a political one shaped by standards processes and institutional power?

On the time bombs, Reid agreed to insert time-dependent deactivation code as a condition of selling Scribe to Unilogic. He later said he was "simply looking for a way to unload the program on developers that would keep it from going into the public domain." Stallman saw this as "a betrayal of the programmer ethos" and famously proclaimed that "the prospect of charging money for software was a crime against humanity." Stallman later described that he "had experienced a blow up with a doctoral student at Carnegie Mellon University. The student, Brian Reid, was the author of a useful text-formatting program dubbed Scribe" (see Williams 2012). The technical implementation of the time bomb, checking system dates, validating license codes, represents an early instance of what we might now call digital rights management (DRM) or artificial scarcity encoded in software. What can CCS methods tell us the code that enforced these restrictions? Do we have access to it, and if so can we undertake an annotated reading of this code?

The clean separation of structure and presentation that Scribe pioneered has become standardised within computing. But it is important to note that this separation encodes assumptions about authorship, expertise, and the vision of labour in textual work. Indeed, not all documents fit this model, such as poetry, visual essays, experimental typography, these resist this structure/presentation distinction. What gets lost when this separation becomes infrastructural and prescribed by code?

Interestingly, Reid's 1980 dissertation is itself a Scribe document, self-documenting the system it describes. This reflexivity, using the tool to present the tool, raises questions about demonstration and documentation that connect to debates about literate programming and reproducible research and I think to the questions we are examining here in CCSWG2026.

Resources

Reid, B.K. (1980) "Scribe: A Document Specification Language and Its Compiler." Doctoral dissertation, Carnegie Mellon University. CMU-CS-81-100. Available from DTIC: https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/tr/pdf/ADA125287.pdf

Reid, B.K. (1978) Scribe User Manual, http://www.bitsavers.org/pdf/cmu/scribe/Scribe_Introductory_Users_Manual_Jul78.pdf

Wikipedia entry on Scribe: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scribe_(markup_language)

Crockford, D. (2007) "Scribe": https://nofluffjuststuff.com/blog/douglas_crockford/2007/06/scribe

Williams, S. (2012) Free as in Freedom: Richard Stallman’s Crusade for Free Software. O′Reilly. Chapter 1 discusses the Scribe time bomb incident: https://www.oreilly.com/openbook/freedom/ch01.html

HOPL entry on Scribe: https://hopl.info/showlanguage.prx?exp=2481

The Source Code (or at least part of it)

This appears to be a distribution take: The overview document is here which gives a good intro to what it contains (although it seems to contain a lot more!)

Main Directory: https://www.saildart.org/[SCR,SYS]/

This module is the `main program' of SCRIBE: SCRCMU.BLI

Simple example of a .MSS file: A.MSS

Next challenge: Can we find the famous timebomb code?

Questions About the Code

How does the @ syntax encode assumptions about the relationship between markup and content? Unlike SGML's angle brackets or later HTML tags, Scribe's @ commands were designed to remain human-readable in the plain text. What does this design choice reveal about intended readers and use contexts?

The dissertation describes "parameterising" the document design into "approximately one hundred independent variables." What model of documents does this parameterisation encode? What aspects of textual form proved resistant to this kind of decomposition?

Reid inserted "time bombs" (!) into the commercial version. This is code that would deactivate freely copied versions after 90 days. This may have been the first software time bomb. What would close reading of such code reveal about the technical implementation of artificial scarcity? For example, a close reading of the time bomb might reveal that "artificial scarcity" is often just a simple IF/THEN statement. It would show (if we can get a copy) how a few lines of code can change a program from a scientific tool (accessible to all) into a commodity (limited by time).

The compiler drew on a "database of format specifications prepared by a graphic designer." This separates the author from the designer as distinct roles with each having a distinct technical interface. How does this division of labour compare with contemporary systems?

Scribe processed manuscripts into device-specific output formats. The Reid's dissertation engages with questions about format translation and media specificity that remain live in discussions of responsive design and platform-specific document production. What can historical analysis contribute to these debates?

LATEST: There are also interesting links to Bolt Beranek and Newman (BBN) and Janet H. Walker, such as:

Walker, J.H. (1981) ‘The document editor: A support environment for preparing technical documents’, in Proceedings of the ACM SIGPLAN SIGOA symposium on Text manipulation. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, pp. 44–50. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1145/800209.806453.

Comments

David, your challenge to locate and close-read the implementation of the first software time bomb was extremely tempting -- I hope someone takes you up on it (or you share a hint as to an entry point).

I went in a slightly different direction, choosing to subsume this productive set of provocations and questions through the lens of your question five ("device-specific output formats" and "media specificity").

Rather than attempt to run the code on an emulated PDP-10, I set the goal of sitting with the code by reimplementing a version of the parser with contemporary device outputs. The plan was to create a standalone JavaScript web interface which could parse classic SCRIBE syntax then emulate classic Device outputs (e.g. write plain text and re-enact a line printer) while also rendering contemporary formats such as HTML, Markdown, and PDF as outputs: classic 1980s syntax recreated using related contemporary methods (such as a Parsing Expression Grammar).

To add one more twist, I decided to walk through the SCRIBE User Manual beginning on the first page, evolving the parser by modifying it so that it could parse the examples given in the documentation, accumulating features paragraph by paragraph and page by page, like kind of literate programming morality play. To turn the experience into a conversation, I fired up an agentic programming environment with Codex and did the first three chapters as discussion of specification and features, a paragraph at a time as a kind of human-agent code book club. The first draft results are here:

Select a sample from the dropdown -- samples 2.2 through 3.4.1 are all excerpts transcribed from the book and being parsed, not by SCRIBE, but by a JavaScript reenactment. Many things came up for me during the process of trying to remake what SCRIBE says it is, including the voice, e.g. how the "non-procedural nature of SCRIBE typically gives fits to people who have grown accustomed to procedural document formatters." The one I'll point out though is perhaps the most obvious even without doing any coding: the examples for parsing are from:

The BLISS source files themselves are also bursting with philosophy, skull ASCII art, and comments that overflow of powerful emotions, but there is something about reading the docs into code like this that felt like a unique engagement with what a privatized, closed, and time-bombed program can still mean through its self-generated manuals. And the example-based or spec-based look at what SCRIBE was changed how I thought about it. It really grabbed my attention when, while explaining the mechanics of Insert statements and the

@Quotation()command/environment, Reid quoting Wilde:Thanks for your great comments, Jeremy. Lots to think about.

You are right to note the quotations in the documents (e.g. user manual from 1978), Malory's Le Morte Darthur. Wilde's The Soul of Man under Socialism. Kipling's Ballad of East and West. These don't look like test cases pulled from whatever books Reid happened to have lying around. They're canonical literature, the Western Canon (reminds me of Bloom 1994, although correct me if I'm wrong but the Wilde is not on Bloom's list? I wonder if Carnegie Mellon had a great books module at the time?). And Reid is demonstrating that Scribe can handle them, can mark them up, can process them, can reproduce them with proper formatting intact.

I think this matters because Scribe arrives at a particular historical moment when humanities computing is beginning to imagine large-scale digital textual archives. The 1970s saw projects like the Thesaurus Linguae Graecae starting to put classical texts into machine-readable form. The Oxford English Dictionary was being prepared for computational analysis (digitalising started properly in 1984). Literary scholars were starting to think about concordances, textual collation, statistical analysis of vocabulary and style.

So, Reid's choice of literature as examples in the Scribe User Manual maybe isn't incidental to this historical moment (1978-80s). Perhaps it aims to stake a claim that Scribe can handle real literature, not just technical manuals or scientific papers. They represent Culture with a capital C. If Reid had used random Lorem Ipsum placeholder text, it wouldn't have made the same argument. Reid needed to show it could handle texts that counted, texts that had literary value, texts worth preserving and reproducing.

I presume that the intended users would recognise Malory, Wilde, and Kipling. They would share Reid's sense of what constitutes literature worth formatting properly. This, perhaps, marks Scribe as a tool for a particular class? Educated, literary, probably linked to the humanities in some way at elite institutions like Carnegie Mellon? The examples can be taken to perform distinction whilst demonstrating technical capability. Which in itself I think is a remarkable historical time capsule of how things were beginning to shift in the way in which we thought about the "digital" and its relevance to culture?

I was at CMU at the moment of Scribe's birth. Many (perhaps all) of my papers and theses were set in Scribe. A slightly interesting culture developed around CMU at that time, of using @(...) markers in our posting and mail. For example: @spoiler(...) or @flame(on)...@flame(off). (I'm not sure how widespread this was, because I was in the heart of it.)

Note: Scribe was written in BLISS-10 (PDP-10) and then probably adapted to BLISS-32 (VAX/VMS)

On Jeff's point:

We can also consult the Scribe Pocket Reference to see how flexible and advanced the text processing was.

I'm wondering if Kirschenbaum's Track Changes: A Literary History of Word Processing (2016) is problematised when we start to look at Scribe, which shows that the category of a "word processor" is a very artificial one. He attempts to carve out a special exceptional status for word processing, but I think it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that something like Scribe meets the definition of "hardware and software for facilitating the composition, revision, and formatting of free-form prose as part of an individual author’s daily workflow... (Kirschenbaum 2016: xiii).

Scribe can do everything the word processor can do. And in fact, many word processors worked in a similar way to Scribe (i.e. the show/hide style function in Word Perfect, for example).

I'm interested in whether the "word-processing parenthesis" (to the extent it can be defended as a category) is closing in an age of AI together with the rise of markdown and new text formats. In fact, I'm beginning to think Scribe is an early anticipation of the direction of travel for the post word-processing world, which he calls the "Writer's Workbench" (Reid 1980: 71). This reminds me of the notion of "context writing", as constructing an informational milieu within which writing takes place, which I discuss in Provenance Anxiety: Death of the Author in the Age of Large Language Models.

A few interesting observations in the structure of the document Scribe: A Document Specification Language and its Compiler

The "Cast of Characters" (Section 1.3)

Reid begins his PhD dissertation not with a technical abstract, but with a "Linguistic Note" and a cast of characters. He defines himself, the reader, and the expert (the designer) as distinct social roles. By personifying the software components and the human users, he frames Scribe as a social contract (a drama?) between an "Educated Author" and a "Mechanical" secretary (the persona of his document). Would this literary framing would be entirely alien to a standard compiler thesis of that era (e.g. for C or Pascal)? It reminds me of the use of persona in Weizenbaum's ELIZA and how he thought about scripts. Reid goes on to argue,

Was Reid was actually trying to create a "LISP-like symbol manipulation" (Reid 1980: 117) inside BLISS, which was a language that had "utterly no low-level support" for strings (Reid 1980: 106). It seems to me that Reid was building a "Humanities" engine inside a "Systems" chassis, which, perhaps, explains why the code feels in such a tension. It was as if the machine was straining to become a secretary.

2. The "Ice Cream Vending Machine" (Section 2.1.2)

To explain the difference between procedural (machine-oriented) and nonprocedural (intent-oriented) logic, Reid uses a lengthy, narrative metaphor about an ice cream vending machine and the "trick" of getting exact change for a bus. This is a style of pedagogy, by explaining high-level logic through everyday narrative rather than mathematical proofs it speaks in a different register to a highly technical report. It suggests an audience that values conceptual elegance and "cleverness" over raw efficiency (e.g. the hacker ethic, and Reid definitely placed himself in the hacker category, even though his software was remarkably well produced and designed due to his background in corporate software development). Reid explains,

The Irony of the "Mechanical Slave"

With the Wilde quote, "on the slavery of the machine, the future of the world depends", Reid is perhaps gesturing toward a claim that formatting is the "ugly, horrible work" of the "slave," and Scribe is the machine that liberates the "Soul" (the Content) of the Author (see Reid 1978: 16). The metaphor of the computer as "slave" is common in ways of thinking about machines at this time – often unconsciously drawing on a system of oppression inverted to become a means of achieving leisure time from mundane work. For example, Christopher Strachey writing in 1954, the computer "behaves as if it were a completely obedient and accurate slave who works with incredible speed, but wholly unintelligently" (Strachey 1954: 25). We might also link this to gender and the assumption that secretaries are usually women, whose work computers might easily replace. As Strachey writes,

The "Forbidden" Manual

In the "Documentation Goals" (Section 10.3), Reid recounts a fascinating piece of social history. As he developed Scribe, he wrote an "Expert's Manual" intended only for for high-level designers. But CMU students and staff began illicitly photocopying it to access low-level commands that bypassed the separation of form and content. He writes,

This is a remarkable instance of a developer trying to restrict user's power to preserve the philosophical integrity of his "markup" vision. It creates the subject position of the "Author" as someone who had the computer processing hidden from them. The ideal author, in Reid's vision, should not know how the machine works. We might note, authors, according to Reid, should not have artistic tastes as they should defer to the "Graphic Designer" who has encoded "proper" typography into the database. It is a very structured, institutional vision of creativity (see Reid 1980: i). I also doubt that many graphic designers would recognise their craft as being a bit like a modern SysAdmin or DevOps engineer who define the "Report" or "Article" definitions in the database using the 100 independent variables. The "Graphic Designer" becomes a kind of typographical bureaucrat, encoding proper form into the system. Authors are not just shielded from the machine, they are explicitly denied aesthetic agency.

I think this links to Reid's Platonic vision of the ideal page (see Appendix B, p. 147). Reid seems to indicate that there was an "Ideal Form" of a page that existed independently of whether it was printed on a low-res line printer or a high-res printer. It is also an example of device-independent programming that allowed the author to focus on the text, not the technicalities of the printing device.

So, this all brings to my mind something I've not clearly understood about CCS. When doing deep reading -- or whatever you call it -- of a book, the book as written is the same thing that the reader reads, so in some sense (that I must admit I only barely get since I'm an engineer not a media analyst) this critical reading actually "touches" the reader. But in CCS it's a very different situation. At CMU -- having been there then -- we all just thought of Scribe as a better paper formatter than troff/nroff. What Brian wrote or said, and his code, meant literally nothing to almost literally any of us since we didn't see the code, neither did we read his rantings -- actually, we did read his rantings on the bboards at the time, but not about Scribe. Probably almost no one except his committee (as far as I know) read his thesis, and I'm sure that no one, including his committee, read his code. So this deep analysis of Scribe and his writings about it are certainly telling us something, but it seems like it has to be tempered/augmented by the user view. Unfortunately, we don't often get the user view because unless you luck out and someone like me happened to be there then, there's no one to offer the user view (again, v. a book where there are book reviews and discussion ad nauseam about most books that would be worth reviewing. Anyway, I don't know how to straddle this chasm, but it seems to me to be important, esp. as I'm reading you writing all this deep stuff about Scribe which was literally to us users just a document processor like all other document processors, but with easier commands. (Actually, I'm not sure that Scribe was that much easier than troff. The big difference as that this was the time of font-capable printers -- CMU was one of the first institutions outside of PARC that had a Dover -- and Scribe was able to do fonts. In fact, your mention of "stolen output" was probably not stolen, at least in some cases -- the Dover's were notorious for fucking up in various physical and computational ways -- not that we would have stopped using them, it was worth these fuck ups for the ability to print complex documents with fonts! But we had a joke called "Helvectica Zero" -- the font that we had accidentally printed our document in when it never showed up! :-)

BTW, to this point: "Was Reid was actually trying to create a "LISP-like symbol manipulation" (Reid 1980: 117) inside BLISS, which was a language that had "utterly no low-level support" for strings (Reid 1980: 106)."

I used BLISS at CMU at that time. I'm not sure I'd say that I was an expert, but I wrote plenty of BLISS code. I'm a little surprised to see the word "utterly" in that sentence. It was a specific feature of BLISS that it had "no low-level support" for almost any data structure. Indeed, this was a specific design feature of BLISS; The idea was that the user community would build up libraries of data structure manipulation code, which would thence be available for use by others. Perhaps Brian was the first to try to do string processing in BLISS, although this seems unlikely. I can see that whoever was the first to try to work with a given data type in BLISS might be frustrated that it didn't already have that as a built-in. By the time I was using it, it had perfectly fine string processing capabilities -- maybe I have Brian to thank for this?

"The dissertation describes 'parameterising' the document design into 'approximately one hundred independent variables.'"

So, since each of the many variables in the JavaScript version of my its name was Penelope looks like this (only each variable holds a different text)

var fine314 = "

It was almost midnight.

I had spent all day taping the photos of

men and women in the bleachers of the Oakland Coliseum

together in one long strip.

The floor of my studio was encrusted with

pieces of tape, half empty coffee cups, beer cans,

and empty bags of peanuts and chocolate chip cookies.

I was still wearing the blue and white checked nightshirt

I wore to bed.

I stretched the strip of photos across my studio floor

and stood back to look at it.

";

and I could add a randomize script as an output option in the Scribe word processor, the whole work could have been done in Scribe without using a separate word processor?

(The JavaScript variable code actually looks like this)

I believe that the variables he's referring to hold things like font definitions, although some of it can be textual (for examples, fixed signitures and that sort of thing). The body of the document isn't broken up into these parameters. (At least as I read this, and see attached example from his thesis.) It's possible that the document was temporarily stored in the database; I didn't read carefully enough to tell whether this is the case or not, but his examples are all parameters like these.

Thanks, jshrager! There may also be an issue here of the not necessarily standard or recommended way that I sometimes use variables in electronic literature authoring systems.

Scribe appears to have been a versatile program with a flexible clear capabilities beyond what is expected in word processors. Thanks for introducing this, David.

In defense of Matt Kirschenbaum’s definition of word processors in Track Changes, he separates hypertext, interactive fiction, and networked environments but then after he says “My focus is on word processors, by which I mean hardware and software for facilitating the composition and formatting of free-form prose as part of an individual author’s workflow," he adds that “The functional boundaries among the preceding technologies are of course porous and to a great extent arbitrary...”

The shift in Track Changes from Matt’s previous elit authoring focus – where "authoring systems" is an often used term -- was surprising. He probably expected issues to arise, although for my part, Track Changes was more interesting than expected.

In case you are interested, inspired by Scribe and its definition as a workbench, I've vibe coded a Critical Code Studies Workbench which might be interesting to compare as an environment within which one can create/read/write but the user doesn't need to know the complex underlying system.

In regard to the choice of @ to mark “structure” in digital text, i.e. “markup,” there is another use of @ in programming systems to codify data as objects, theoretically not totally disconnected from textual markup. I’m thinking of the use of Standard ML (also big at CMU!) by Pericas-Geertsen to define an object calculus in which @ denotes object transformations analogous to lambda operations, i.e.

@(x)(x.iszero := false).pred := x.Standard ML represents a fortuitous slippage, as it stands for “Standard Module Language” even if it reads like markup language, an ML, etc. The above expression constructs the data “x” as an object with attributes, i.e.

.pred(the condition of being a predecessor in a sequence). In the 2010 CCS working group, I tried to read this calculus as an investment of desire in objects, without making—at the time—any connection to markup languages.I wonder if @ lends itself to these kind of expressions

(@(x)(x.iszero := false).pred := x)and gets at why @ used to “structure” text in Scribe may be a more elegant way to mark up text, compared to say, XML tags. Conversely, could the institutions of corporate programming that heavily used object-orientation in the 1980s and 1990s (as a strategy for greater logical control, even if Standard ML is not purely object-oriented) be connected to Unilogic’s impulse to enforce digital rights management? Just a thought.