Howdy, Stranger!

It looks like you're new here. If you want to get involved, click one of these buttons!

Categories

In this Discussion

Week 2: AI, Vibe Coding and Critical Code Studies

Vibed using CapCut

Vibed using Veo 3

"I'm ready to help you plan, study, bring ideas to life and more..." (Gemini 2026)

"Vibe coding" emerged in early 2025 as Andrej Karpathy's term for a new mode of software development. He wrote about fully giving in to the vibes, embracing exponentials, and forgetting that the code even exists. The phrase captures something novel about writing software through conversation with large language models (LLMs) as a practice where natural language prompts replace direct code authorship, and where working programs emerge through iterative dialogue rather than deliberate deterministic construction. For me, vibe coding lies somewhere between augmentation and automation of software writing, but I think it also raises new questions for Critical Code Studies (CCS).

For CCS, vibe coding poses real opportunities for innovation and creativity in new methods for code reading and writing. Over the past year, experimenting with vibe coding, such as building tools and experimenting with failures, has convinced me that in terms of how we might undertake sophisticated code readings, vibe research (vibe CCS?) has something interesting to offer us. I have vibe coded a critical code studies workbench that you can download and use to undertake different types (modes) of CCS. Full instructions are here.

This thread draws on on a case study I've already documented, which involved building an Oxford TSA practice application with Google Gemini, and then subsequently attempting to develop an "AI sprint" method that adapts book sprint and data sprint approaches for LLM-augmented research. Rather than approaching LLMs primarily as tools for reading code (i.e. the hermeneutic direction) or generating code (i.e. the software engineering direction), this group's discussion will aim to focus on what happens in the space between, that is, where prompts become interpretive acts, where code becomes a mirror reflecting gaps in our own thinking, and where the boundaries between human and machine contribution become productively blurred.

Theorising Working With AI's

Working through extended vibe coding sessions, I've found it useful to distinguish three different ways of engaging with AIs.

Cognitive delegation occurs when we uncritically offload the work to systems that lack understanding. In my TSA project, I spent considerable time pursuing PDF text extraction approaches that looked plausible but were unworkable. The LLM generated increasingly sophisticated regular expressions, each appearing to address the previous failure, while the core problem, that semi-structured documents resist automated parsing, was ignored. The system's willingness to produce solutions obscured that the solutions the LLM offered were broken, failed or misunderstood the problems.

Productive augmentation describes the sweet spot in working with an LLM. This is human curation of the LLM combined with the LLMs speed and efficiency to create code. Once I abandoned text extraction and instead remediated the PDF within an interactive interface, progress on my project accelerated dramatically – in other words, it was up to me to rearticulate the project and realise where I was going wrong. In contrast, previously the LLM would cheerfully tell me that my approach was correct and that we could fix it in just a few more prompts. By actively taking over the coordination and curating the design and structure of the research questions and design decisions the LLM handled coding I would have struggled to produce myself (and certainly at the speed an AI could do it!).

Cognitive overhead is what I call the "scaling limits" of vibe coding. Managing LLM context, preventing feature regressions (a common problem), and maintaining version control are irritating for the human to have to manage as it seems like that should be the job of the computer. However, due to a range of reasons (e.g. misspecified or mistaken design, context window size, context collapse, bad prompting) a project soon reaches a complexity threshold where the mental labour of scope management became impossible of the LLM to handle and exhausting for the user. I think this means that perhaps vibe coding works best for bounded tasks rather than extended development (or at least present generations of LLM do, as this is clearly a growing problem in deployment of these systems).

Vibed using Nano Banana Pro

Day 1: Question for discussion

When you try vibe coding (and you should!), do you recognise which mode you occupy?

What signals the transition from productive augmentation to cognitive delegation? Is it an affective change or a cognitive one?

Vibed using Nano Banana Pro

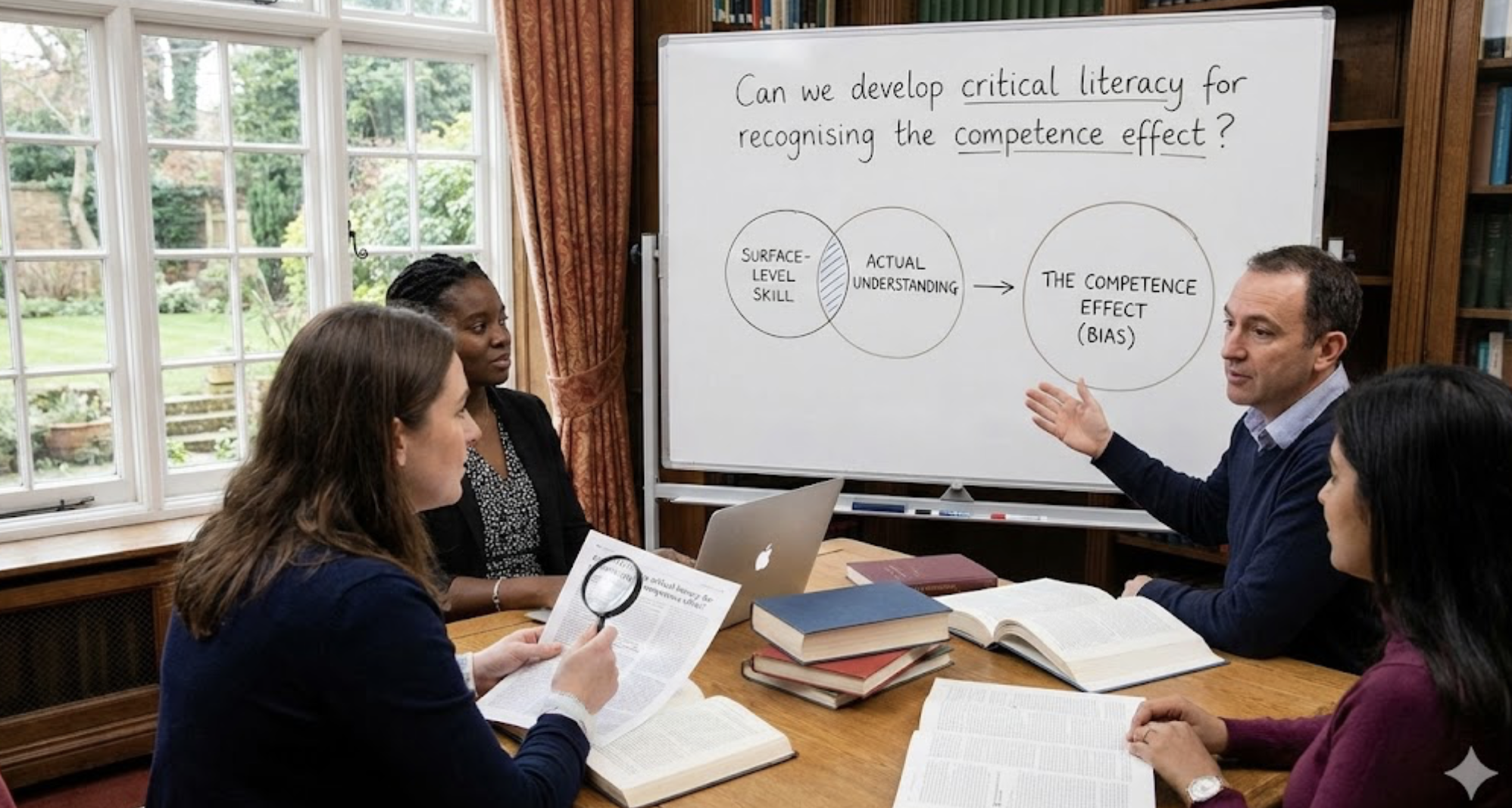

The Competence Effect

The 2024 AI and CCS discussion returned repeatedly to Weizenbaum's ELIZA effect, which is the tendency to attribute understanding to pattern-matching systems. I want to suggest that vibe coding produces something qualitatively different, which I'm calling the competence effect.

Where ELIZA users had to actively ignore (bracket out?) the system's obvious repetitiveness, vibe coders receive constant reinforcement that the LLM "gets it". The AI always tries to be positive and action your suggestions and prompts. Bugs seem to get fixed through iterative prompting, and the system appears to learn from corrections. Quasi-functioning code provides evidence that seems to support that the LLM is helping you, even as it has no real understanding of your intentions.

The danger lies in a subtle mistake. A projection of competence and positivity from the LLM actually obscures the distinction between pattern-matching and comprehension. The LLM's apparent responsiveness creates a false confidence in its flawed approaches. We persist with unworkable strategies because the system generates plausible-looking code without signaling architectural problems (or perhaps even being able to do so). It tells us our idea is great, and that it can build the code – and if we don't keep a critical eye on the development, we may waste hours and days on an unworkable solution.

Day 2: Question for discussion

Can we develop critical literacy for recognising the competence effect?

What textual or structural markers distinguish real LLM capability from a surface plausibility?

Intermediate Objects as Hermeneutic Sites

A key principle that emerged from my AI sprint method was that "intermediate objects" were hugely helpful in keeping track of how successful the approach was. These include tables, summary texts, JSON files, and extracted datasets. These make algorithmic processing visible, and contestable, at steps along the way whilst vibe coding. These "materialised abstractions" serve as checkpoints where you can verify that computational operations align with your interpretive intentions.

CCS tends to examine code as a singular cultural object. But interestingly vibe coding produces chains of intermediate objects that themselves potentially become sites for critical reading. For example, the prompt history reveals the distribution of agency and versioned code (you must tell it to use versions!) shows where architectural decision points where made at different moments. Indeed, even the debugging conversations can help examine assumptions about what the system can and cannot do.

Day 3: Question for discussion:

Can we perform CCS on code that exists in a kind of "perpetual draft form", continually revised through human-LLM dialogue?

Should we be reading the code, the prompts, or the entire conversation as the primary text? What is the research object?

Vibed using Nano Banana Pro

The Hermeneutic-Computational Loop

Hermeneutics can be said to involve dialogue between interpreter and text. In contrast, vibe coding creates a three-way exchange between (1) human intention expressed through natural language prompts, (2) machine interpretation and code generation based on statistical patterns, and (3) executable code requiring further interpretation and testing.

This triadic structure challenges Gadamer's dyadic model of hermeneutics. Instead, understanding emerges through iterative cycles (i.e. loops) where each prompt is an interpretive act and a request for computational response. Code becomes a kind of mirror, reflecting intentions back while revealing gaps in your initial thinking. The 2024 discussion, AI and Critical Code Studies, touched on this noting how "the AI prompt becomes part of the chain of meaning of code".

Day 4: Question for discussion:

Does vibe coding represent a new hermeneutic approach for CCS? Or a supplement to it?

Is there a difference between collaborative coding with an LLM as against collaborative coding with a human partner, or, indeed, from working in sophisticated Integrated development environments (IDEs) with autocomplete?

Provocations

A team of us has been working on ELIZA for several years now, and the comparison with contemporary LLMs keeps returning. But I think the competence effect marks a qualitative break. ELIZA was obviously limited and its power lay in users' willingness to project meaning onto its mechanical responses. In contrast, LLMs produce outputs that pass functional tests, as code that runs, prose that (sometimes) persuades, analysis that (might) appear sound. I think the critical question shifts from "why do we anthropomorphise simple systems?" to "how do we maintain critical distance from systems that perform competence so convincingly?"

If an LLM can generate bespoke analytical tools from natural language prompts (and it clearly can), what becomes of the methodological commons that has been used to justify digital humanities or digital methods as fields? My AI sprint method attempts one response by integrating LLM capabilities within traditions that emphasise interpretation, critique, and reflexivity rather than abandoning methods completely. But I'm uncertain whether this represents a sustainable position or a rearguard action (it is also often feels somewhat asocial?).

My TSA project involved approximately 4 hours of vibe coding, apparently (according to the LLM) consuming 0.047 GPU hours at a cost of roughly $0.20 (!). This apparent frictionlessness conceals questions that CCS is well-positioned to raise, such as whose labour did the model appropriate in training? Under what conditions was that knowledge produced? What material resources make such co-creation materially possible? The collaborative interface "naturalises" what should surely remain contested.

Vibed using Nano Banana Pro

The Discussion

Some questions to consider:

Have you tried vibe coding? What modes of cognitive augmentation did you encounter? Where did delegation shade into "productive collaboration" or "cognitive overhead"?

Are these three modes I've identified similar to your experience, or do they need refinement? Are there other modes I'm missing?

Can you share examples of your LLM-generated code that appeared ok but failed? What made the failure difficult to recognise?

Is vibe coding a good method, or object, for CCS? What would CCS methodology look like if its primary objects were vibe coding sessions rather than code artefacts? What would we read, and how?

Can we vibe code tools and methods for analysing code? Or to what extent can LLMs help us analyse vibe coded projects?

Is this the death of the author (redux)?

I'll be posting some code critique threads with specific examples from my projects, and proposing a mini AI sprint exercise for those who want to try vibe coding during the week and reflect on the experience together.

Resources

Vibed using Nano Banana Pro

For those new to vibe coding

Karpathy's "Software Is Changing (Again)" talk: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LCEmiRjPEtQ

My "Co-Writing with an LLM" case study: https://stunlaw.blogspot.com/2025/10/co-writing-with-llm-critical-code.html

My "AI Sprints" methodology post: https://stunlaw.blogspot.com/2025/11/ai-sprints.html

The Oxford TSA Questionmaster code: https://github.com/dmberry/Oxford_TSA_Question_Master

Berry and Marino (2024) "Reading ELIZA": https://electronicbookreview.com/essay/reading-eliza-critical-code-studies-in-action/

For the previous CCSWG2024 AI and CCS discussions

AI and Critical Code Studies: https://wg.criticalcodestudies.com/index.php?p=/discussion/157/ai-and-critical-code-studies-main-thread

ELIZA code critique: https://wg.criticalcodestudies.com/index.php?p=/discussion/161/code-critique-what-does-the-original-eliza-code-offer-us

LLM reads DOCTOR script: https://wg.criticalcodestudies.com/index.php?p=/discussion/164/code-critique-llm-reads-joseph-weizenbaums-doctor-script

Comments

I'll start with a vibe coded ELIZA on Google Gemini Pro (2026):

Prompt: "create a working version of ELIZA in the smallest code (loc) you can."

Result:

I'm fairly new to vibe coding and was poking around with a sonification task to parse some command line data into sounds as a prototype and found myself in cognitive delegation for a while to see what CoPilot could do.

Use the below data to create a wav file. The event time is the first part of the line before ->. The second part needs to be split by ':'. The first number is CPU power. The second number is GPU power. The third number is ANE power. The fourth part is GPU power. Ignore the mW part in each. Use the number to calculate a new number from 440Hz.I felt that I had to specify a few things initially and to provide some dummy data to work with and support the initial context. I found that it could handle simpler prototyping tasks, but more complex ones failed when run. CoPilot cheerfully ignored this, even when it ran the code itself and produced an silent audio file. (Writing this comment is making think about using one of the code models to see if it can fix it at some point.)

I found that I moved towards a productive augmentation approach to explore different options and to fix some issues. I was still unable to get the more complex version working as did CoPilot but it cheerfully carried onwards. The shift, for me, was to become more engaged with the process and trying to shape the context to be more useful for both parties. This also got me thinking about what I was asking for and how I asked, while being aware that it is trained using other codebases.

I asked it to explain the code, which it did. However, it is very descriptive and makes assumptions. I am wondering if these might also be pointers to the type of code that the model is trained on and provides a way of "reading' or engaging with it. However, I am probably going into other days here.

`

import numpy as np # NumPy for numerical operations and array handling

import wave # wave module for reading/writing WAV files

import struct # struct for converting numeric data to binary format

It contains invalid values and an overflow.

As a curiosity, might a CCS method contain using LLMs to explain code in general and then to move in and out of parts of the code to explore in more detail? However, would this be limited/affected by the context that is generated in the session?

I have vibe coded a critical code studies workbench that you can download and use to undertake different types (modes) of CCS. Full instructions are here.

As I anticipate needing to dip in and out of this thread as the week progresses and I am not always able to devote time per day, I want to begin to address some of the discussion questions based on my own experiences working with GitHub Copilot (mostly Claude Sonnet 4.5 and some with Gemini Pro 2.5 Pro.)

First, it is worth giving some context. I teach programming to students who, for the most part, identify as designers and artists. There are some who aspire to program for larger companies, but most are in the designer, artist, or hybrid status. Having discussed the role of generative AI, which is different from, say, pathfinding or other "AI" commonly used in game programming for decades, most of them HATE it. They don't use. They don't like anything having been touched by it, and some don't even want to talk about it. From their perspective, the future jobs they imagined for themselves are being "taken" by generative AI tools as they see the art and design work of people they like or follow being replicated by algorithms.

Into this mindset, starting in late-2025, I wanted to work more with generative AI tools and experiment with "vibe coding" some myself. One of my successful experiments -- as not all of them were! -- was the creation of a tool to help me unpack the learning management system Canvas' course exports back into files and folders. (You can find it on GitHub as CM-Packer.) Having played around with suggesting patterns or approach, I have found, as David mentions, using "tables, summary texts, JSON files, and extracted datasets" very useful. If you can feed the generative AI a pattern to follow, or the technical requirements, it can often generate something to read or write some format.

Let me quote from the discussion around this idea before I leave my answer:

Everything. If people are not aware, part of the success of GitHub Copilot (and other chat-based tools) is not that they get better, although some people perceive it as such, but that they keep the entire conversation as reference. If I have a longer chat with Copilot about the structure and content of a code project, it "remembers" (i.e. the chat is saved and then re-read) all of those interactions. The longer it succeeds, the more there is to build off of as a pattern to then use in the future. The conversation becomes another data point. The LLM is not getting better; it can't. There is just more data for it to interpret.

In the discussion of "Where is the critical?" for critical code studies, one of the central texts as part of code generation using vibe coding is the conversation, the blackbox it was fed into (the generative AI), and what was produced. Put another way, we need to know the input and output of the system. If we cannot access the code, we must look to how the process translates what was entered with what we receive. An important element to LLM usage is that they are not deterministic. You entering something and me entering the exact same thing will result in different things. However, the conversation, the transcript, reveals how the user approached the problem, supplied data, or corrected the generation, which would be lost otherwise.

This is gotten slightly long, but something I encourage people to try is to start a vibe coding experiment and then start lying to the tool. If it produced blue, say it was red. If it drew a box, call it a circle. The tool assumes you are always acting in good faith, and has been programmed, at least GitHub Copilot has, to apologize if it interprets it got something wrong. Some students I asked to do this stopped quickly as, to speak to the "competence effect," most people become upset when the computer keeps apologizing for mistakes it interprets it might be making when it has not made those.

I have a great deal of experience coding with AI assistance. (I hate the "v" term!)

Today, for example, I used AntiGravity to build an entire prototype app for a children's version of a project management system. It took about an hour. If I could have done this at all before, it would have taken me days straight. (I honestly don't think that I would have been able to do it at all before because I'm not a react programmer.)

I've been doing it now for something like 2 years, more or less every day. I've developed a practice of getting one agent to write code, and then I have a separate agent (not just another discussion with the same agent!) critique the code created by the first agent. Sometimes I have to do this for several rounds before ending up someplace useful.

The AntiGravity example above was a good experience, but I've had bad ones as well -- some extremely bad. The worst cases are where the AI hasn't written all the code itself in the same thread, and the code is large enough, and hasn't been factored in an obvious way. Then the agent can't figure out what's going on, and just makes a mess.

For example, I've been trying to use several different agents over several months to debug my IPL-V/LT implementation (as discussed in the thread elsewhere this week). This has gone very badly. It's a very complex and subtle problem, but even a beginning human engineer would be extremely helpful to me because they would be able to understand IPL-V once they had it explained to them, and would be able to do things that I ask them to do in long complex traces. The AIs get some idea in their head of what's going on, and then follow i down a rabbit hole. Over the AI the AIs (four or five different ones that I've worked this problem with) have jumped to conclusions, and tried to implement what we call "band aid" solutions, for example: "I see that F123 is breaking because it got passed a zero argument. I've patched it so that when it gets a zero, instead of breaking, it just returns a zero." This is OBVIOUSLY not the way to fix this problem! The problem is why is this function being passed a zero?! So I tell it that, and it just moves the bandaid up to the next level, but we're 50 levels deep in the code! It needs to get a wholistic sense of what's going on, but they seem unable to do this -- that is, to get a larger sense of the code base, especially if it's big and they haven't written it!

Now, you might say to yourself, well, this is true for anyone -- if you (I) didn't write a giant pile of code, And, of course, this is true, at least initially upon approaching a large code base that I didn't write, I wouldn't have a wholistic sense of it either, but I don't think that this makes the case. First off, actually I'd probably ONLY have a wholistic sense of it -- unless it's really bad spaghetti code, I'd be able to tell what parts of the code as doing what. I'd have more trouble going into the details than I would of having the wholistic picture. Furthermore, the author (me in this case) could explain the wholistic sense as needed to a human assitant. I've tried to do this to the LLM, but it loses context, and I have to re-explain things over and over, and finally I give up.

So, what about David's interesting questions: What is the unit of analysis? Well, at the end of the day, the thing that matters is the code, so at the end of the day the unit of analysis must be the code. One might think of the prompts as comments, so these bear something like the relationship that comments, or perhaps block comments, bear to the code. When we read code we also read the comments, and the relationship that the comments have to the code depends on what kind of comment they are -- block comments on functions, modules, line comments explaining why something weird is being done -- and remember that the names of functions and variables are effectively comments as well!

One final thing that I think worth mention, since David brought up ELIZA, reminding us of MIT's early contribution to AI: In the 1980s there was a major GOFAI project at MIT called the Programmer's Apprentice:

https://dspace.mit.edu/bitstream/handle/1721.1/6054/AIM-1004.pdf

It's interesting to look at their goals and approaches and compare these to the-v-word as it ended up when it finally came to fruition some 40 years later!

I’m a few days late to this so I”m kind of jumping around discussion questions as more of a thought dump, hope that’s okay.

I've played around a bit with vibe coding, initially at the encouragement of professors in grad school, usually as a quick way to transpile ("if you know how to do it in python, use chatgpt to convert it to r") or as an alternative to rubber-ducking, but just started a class that seems to allow full use of it as long as the code is properly cited.

I've found myself using it for help debugging and been unnerved that it works better speaking to it like I would another person. This is presumably because it’s trained on all of stack overflow and you’re more likely to pattern match something int he form of a conversation like “I’m trying to but instead I’m , this is my code:

and I’ve already tried ” vs something like:Expected result:Actual result:

Generally I find myself falling into “Productive Augmentation” but I feel like it’s easy to slip into “Cognitive Delegation”. I feel like I should note that I’ve primarily tried using chatgpt’s website/app, and that I found the vscode integration to be slower/less accurate in my workflow, but I think features like using information from other chats aid in slipping into the Cognitive Delegation because it will make suggestions using that information I wouldn’t have necessarily come to on my own.

Something I think is worth noting here is that I feel this will make worse a phenomenon that is already been seen for the past few years online. The decline of online forums, especially as servers go down and they get removed from the internet outside of archives, has meant a decline of searching for a problem and finding different people discussing it over the years and using that knowledge for yourself. The rise of things like slacks and discords, some of which do not preserve history, means that even figuring out where to search for the information is less obvious. Others have written about this much more eloquently than I have, but I feel like this is going to develop even further as these sorts of discussions happen in relative private with LLMs. I worry also could affect future training of coding assistants and therefor their longevity.

Even though I’m not sure that’s a perfect argument for why the entire conversations should be part of the primary text, I think that’s why my gut is leaning that way.

I enjoyed the fun campy presentation of this provocation -- including the outrageous CapCut and Veo3 generated videos, the Nano Banana generated fauxtography and illustrations, and leaning heavily into "vibe" as a term.

The meditation on cognitive delegation, productive augmentation, and cognitive overhead all provided helpful framing. It seems to me that there is a kind of "rule of three" being used to describe different degrees (and scales) of engagement, as well as the suggestion of a kind of "Goldilocks principle." While the vibes of cognitive delegation are too soft / too cold, and the scale of cognitive overhead is too hard / too hot, (cognitive) augmentation is 'productive,', which is to say that the middle term is "just right."

Your grounding the term "vibe coding" in Andrej Karpathy's original quote really crystallizes for me why the term makes so many people uncomfortable. Vibe coding is often used as a synonym for cognitive delegation specifically, rather than for the general spectrum of various coding activities which involve (LLM) agents. In this sense the "vibe" is already a self-parody that centers hands-off and one-shot work while de-centering everything else: agent-human pair programming, human coordination of agent teams, human micromanagement of an agent, system architecture and spec-driven development... and even more exotic things, like designating an LLM agent as you manager and having it task you with implementing a project of its devising while it supervises.

Of course these concepts are all evolving rapidly. Karpathy can popularize a cognitive offloading meme-term in February, be distance himself from it in October, and be drowning in cognitive overhead by December.

I associate the "productive augmentation" Goldilocks zone with more dignified (or pretentious) terms than "vibe," such as Addy Osmani (Director of Google Cloud AI) on "AI-Assisted engineering". The term clearly includes the more belt-and-suspenders spec-driven approach of e.g. AWS Kiro, but it seems to clearly exclude vibe coding (vibing is not engineering). For a genera term, I currently prefer "agentic coding" which often seems sufficiently neutral to encompass the vibe and the engineering spec. But again, these terms are all rapidly evolving.

The critical code studies workbench looks fascinating. Two years ago this working group was discussing e.g. how local RAG might help lower the barrier to entry to CCS through connecting an agent directly to a code document store; the concept of LLM workbench software as a barrier-lowering method for more and broader and different engagement with CCS (not offloading) gets me excited about the idea of domain-specific LLM applications such as this one. I am looking forward to trying it out (or even forking it and toying with a custom feature branch, developing some pulls (or even working with an agent to do that)). Currently when using agentic coding (e.g. in VSCode with Codex, Claude code, or ollama) there are seldom any vibes to be had. I usually disable even the ability of an agent to make local commits or access the network without requesting per-action escalation, so that every significant step of every exchange necessarily runs through me for approval and feedback. That said, this post has partly encouraged me to think more about trying out a wider variety of different modalities -- including real vibe coding -- so that I can better reflect on them and adjust my engagements in project-specific and situated ways.

Nevertheless, I often experience a very steep drop-off in my ability to introspect on agentic coding, starting at a comfortable "I experienced the entire commit history of this project" and descending quickly to "a few commits may have slipped past me here and there, so now there might be a bunch of stuff in the codebase that I honestly have no idea when it got there or where it came from or why." This makes me uncomfortable, perhaps because I can trust my human coding interlocutors to take responsibility for their own code, but in agentic programming I feel that ultimately responsibility for every line must with me (it cannot be "Claude's fault"). Perhaps this is partial a transfer from another domain: my also being a professor of literature discussing analogous questions with my students about the future of the college essay and writing in general. To the extent that I am inflexible, it may be a mix of a general struggle to relinquish control, a revelation that the true point of my coding was often experiential rather than utilitarian the entire time, an unproductive fetishization of craft, an addiction to the dopamine hits of micro-progression, or maybe a real idealism about code writing at its best being an art that crystalizes one's own thoughts, and thus something more like a love letter than a math test.

Great topic - thanks to David and other contributors. The workbench looks wonderful - if only I had time to play! This could certainly be placed in the context of 50 years research into human factors of programming, at venues like the Psychology of Programming Interest Group (PPIG). However, much of that research, although addressing questions very similar to those here, and making similar observations, was grounded in controlled experimental methods from cognitive science, or organisational studies. The end-user programming community does work that more resembles this thread, although perhaps the auto-ethnographic reflections of these posts are more typical of craft studies, a field that has engaged with PPIG to a more limited extent, somewhat in my own work, and from reflective live coders such as Alex McLean and Thor Magnusson.

Perhaps the challenge that CCS might engage with here is to ask what essentially critical interventions are needed? One increasingly concerning to me is that my defence against the Singularity was that no programmer would be silly enough to deploy machine-generated code that they didn't understand, and no engineer would connect such code to an actuator. The enthusiastic uptake of "vibe" demonstrates that I was insufficiently pessimistic. I do work quite closely with companies creating the latest generation of AI-assisted IDEs, and my students continue to experiment with alternative design strategies. If readers of this thread would like to interact with the tool designers, then PPIG, or PLATEAU, or VL/HCC should be pleased for some more critical resource!

Exciting news. Much development later - who knew that creating realtime collaborative annotation systems would be much harder - we have an online shared project annotation system.

TRY IT HERE

New collaboration mode allows multiple people to work on annotations at the same time using Google or Github login or magic link using email address (nothing is stored btw).

In cloud collaboration mode you can create projects with source code etc and share the annotation work together.

You can also invite people to your projects:

Also due to popular demand CCS workbench now has an improved UI system with the latest AI system to help with annotations. He's back, yes I know you'll be pleased...

Welcome back to Clippy!

Clippy uses the most advanced new system of AI intelligence to sense when you most need his help. Clippy can be summoned by an elaborate incantation that needs to be typed into the app (anytime except in a text box). Feel the power of the 1990s office assistant powering your productivity!

TRY IT NOW!

cc @markcmarino @jeremydouglass @AlanBlackwell

@davidmberry Clippy is killing me!

I'm excited to try collaboration out! I have one question about the web-hosted version / Cloud collabotation mode and how AI is handled in practice?

Regarding the hosted instance at https://ccs-wb.vercel.app/ and online realtime collaboration: It might help to clarify this for people (given that some API keys have tokens that run out, or can result in actual charges):

I suspect that I know the answers, but I'd love to hear it from the source.

Ok, so @jeremydouglass I will try to understand your questions.

This system is a result of a previous experience of trying to co-annotate the ELIZA code between 8 people and it was a bit of a nightmare in Google Docs. So I have attempted to make the process a lot easier and a lot more interesting as you can see other people working (I have a presence system planned but not yet there, but the annotations are shared using realtime updates from the database).

By API key do you mean OAuth login? That is handled just for identification.

If you mean for the LLM, that is purely for your local version.

All LLM use is local. The chat is purely you talking to the LLM in your instance.

The collaboration logic handles projects only, and inside projects you can share code files and annotations of those files in real time - this took me a long time to get right. Note the lovely flash when someone else annotates the code also note the (I think) nice animation to draw your attention to where you click the + to make the annotation.

also note the (I think) nice animation to draw your attention to where you click the + to make the annotation.

Nice things to looks out for 1: realtime annotation support. 2. Syncing files when you add them to a project. 3. Local mode, for the people who don't want to share. 4. A library of projects that you can add to 5. skins for those still missing MySpace, 6. a secret easter egg, not just Clippy, but Hackerman (actually hacker-clippy)!

No, the LLM can be turned off (AI OFF) and it makes no difference to the annotation. The only thing the LLM can do is comment on your (and colleagues) annotation if prompted as it keeps an LLM context, which you can see if you click in the chat.

I suspect that I know the answers, but I'd love to hear it from the source.

For a test example here is the

ELIZA 1965b code, clean version, partially annotated version, and DOCTOR script.

@jeremydouglass full instructions on the infrastructural and resource needs of setting up CCS workbench and the backend database etc. are given in these docs:

Deployment and Development Infrastructure for CCS workbench

And don't forget this crucial document from the AI's perspective.

I've been sitting with this thread for a while, so much so that I decided to work through my feelings about vibe coding by writing my fourth dissertation chapter about it. After a lot of exploration of existing tools, their user manuals, and discourse surrounding them, especially after the release of things like Gas Town, I find it unfortunate how much of the technospeak of neoliberalism and Web 3 has manifested around vibe coding. It all feels quite hustle culture and passive income to me. But what I think hits me the most is how much it dissociates us from the substrate of code itself. If we are not looking at code, or we are treating it as something that we can separate from the overall trajectory of a code base and that which evolves from it, are we not rejecting a primary notion of critical code studies, that code is a rhetorical material that layers and layers to create meaning from line to interface? That if we want to understand a system, we must look at the code? As someone who studies programming languages as unique linguistic instances, I'm not sure this flattening of code does anything significant beyond continuing to push a culture of technological black boxing, not simply by having the generation of code pushed further to the margins by making AI do it, but also by creating a culture around code that says that the code does not matter and that looking at it or doing it yourself is for purists. I'm still working through this all theoretically, and I understand it from a practical sense, but I think this is one of those short-term gain, long-term loss things for the techno culture.

Hi everyone. I'm coming to this conversation late, which gives me the advantage of reading and learning from a fascinating discussion before diving in. There's a lot in this thread that echos what I've been struggling with in my thinking about "vibe" coding, and I share @bee.rinaldi's impression that the term can get caught up in techbro neoliberalism, and that the blackboxing effect only deepens the sense of stratification between those who code "for real" and those who can only "vibe."

Like @dancox , I am seeing how this plays out with students, and I see some of the same thing: my students for the most part hate generative AI. At the same time, in my current class (web design), while I've forbidden any AI tools at least for now while we focus on fundamentals, it's pretty clear that some are probably using it to complete their assignments. This is an example of uncritical cognitive delegation committed in bad faith (and falling to the competence effect -- which is an excellent formulation), but what may be interesting for a CCS perspective is that for these students, the things they clearly haven't grasped yet are those chains of intermediate objects. (In my case, I have spent hours within the last week explaining and re-explaining how file names, folders, and relative paths work.)

I'm not analyzing student work for linguistic or rhetorical features, but I think what's analogous is that the evidence for the thing I want to know ("does this student know what they're doing?") lies somewhere beyond single code artifacts or projects. Instead, it's the whole context that brings the project into the world, so if an agentic coding workflow or IDE is part of a software projects origin story, it seems reasonable to study that as part of the chain of intermediate objects for study.

Another thing I'm interested in tracking related to all this is the figuration of "code" rhetorically. For example, I have a colleague who is quite keen on embracing AI but doesn't have any programming experience. He's pitching some new AI-centered curricular things, and one of the selling points is that it will develop AI "skills", one of which is "no-code app development." I haven't figured out how to square those two claims, because the latter just seems like cognitive delegation to me. Or maybe I'm too much of a DIY purist. Or is vibe coding itself really a "skill"? The discussions and nuances in this thread make it clear that there are different ways to go about it, some of which might be "right" or "wrong", but are any of those nuances legible if the proposition is to avoid code entirely?

Thanks for the comments, I've found this a very productive and thought-provoking discussion.

I have blogged about the experience here with some reflections on what this AI method implies (Vibe Decoding: Building The Critical Code Studies Workbench) and some questions about how we might need to think critically about it, particularly its tendency to destroy an archive of work – if one isn't careful!