Howdy, Stranger!

It looks like you're new here. If you want to get involved, click one of these buttons!

Categories

In this Discussion

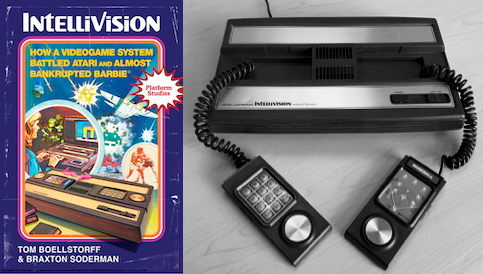

Book: Intellivision by Tom Boellstorff and Braxton Soderman

Tom Boellstorff and Braxton Soderman's Intellivision: How a Videogame System Battled Atari and Almost Bankrupted Barbie® is our featured book discussion for this week. The book is available from the MIT Press in paperback / ebook, and also open access PDF.

Left: cover of the _Intellivision (2024) book. Right: black and white photo of the Intellivision videogame system._

From the MIT Press:

The engaging story of Intellivision, an overlooked videogame system from the late 1970s and early 1980s whose fate was shaped by Mattel, Atari, and countless others who invented the gaming industry. Astrosmash, Snafu, Star Strike, Utopia—do these names sound familiar to you? No? Maybe? They were all videogames created for the Intellivision videogame system, sold by Mattel Electronics between 1979 and 1984. This system was Atari's main rival during a key period when videogames were moving from the arcades into the home. In Intellivision, Tom Boellstorff and Braxton Soderman tell the fascinating inside story of this overlooked gaming system. Along the way, they also analyze Intellivision's chips and code, games, marketing and business strategies, organizational and social history, and the cultural and economic context of the early US games industry from the mid-1970s to the great videogame industry crash of 1983. While many remember Atari, Intellivision has largely been forgotten. As such, Intellivision fills a crucial gap in videogame scholarship, telling the story of a console that sold millions and competed aggressively against Atari. Drawing on a wealth of data from both institutional and personal archives and over 150 interviews with programmers, engineers, executives, marketers, and designers, Boellstorff and Soderman examine the relationship between videogames and toys—an under-analyzed aspect of videogame history—and discuss the impact of home computing on the rise of videogames, the gendered implications of play and videogame design at Mattel, and the blurring of work and play in the early games industry.

Intellivision is a part of the Platform Studies series at the MIT Press edited by Nick Montfort and Ian Bogost, who write in their series forward that "there is also much to be learned from the sustained, intensive, humanistic study of digital media. We believe it is time for humanists to seriously consider the lowest level of computing systems and their relationship to culture and creativity." They describe books of the series as sharing:

- a focus on a single platform or a closely related family of platforms

- technical rigor and in-depth investigation of how computing technologies work

- an awareness of and a discussion of how computing platforms exist in a context of culture and society, being developed on the basis of cultural concepts and then contributing to culture in a variety of ways— for instance, by affecting how people perceive computing.

For our book discussion of Intellivision in this Critical Code Studies Working Group, we will focus on engagement with code and code work. In the book these passages are situated within a broad study of the Intellivision platform and its many historical and cultural contexts. In the opening passages of their introduction ("Introduction: Intelligent Visions": "Blue Skies") the authors frame this situated approach:

We dig into the dirt, so to speak, revealing multifaceted technical and social practices that shaped the platform. We investigate Intellivision’s origins, computational properties, and videogames. We examine its design, advertising, and marketing. We introduce the companies who collaborated to produce it and the people who worked to develop it. We also look outward, reflecting on what Intellivision teaches us about videogames, platform studies, and the social history of technology.

Intellivision’s fascinating story is about a major toy company enter- ing the nascent videogame industry and the wider market for consumer electronics and home computing. It is a story about competing visions for the future of videogames, about the exhilarating and risky experience of exploring uncharted markets, about the intoxicating boom of success and agonizing plummet of failure. It is a story about a videogame system that battled Atari and almost bankrupted Barbie—and along the way, it changed the history of videogames.

Our starting focus for discussion is drawn from Chapters 4-6, and in particular Chapter 5.

- 4 Mattel’s Marketing Magic 107

PART II: Practices- 5 Ladders of Game Production 145

- 6 Becoming a Videogame Programmer at Mattel 167

Linked open access Chapters 4-6, from the Table of Contents.

In this key passage from Chapter 5 (pp150-151), the authors quote APh programmer David Rolfe on the cartridge and EXEC operating system before working through a short code routine from the Intellivision game Major League Baseball written in CP1610 assembly code. The quote and their worked examples explores the relationship between platform-os and software as a relationship between 'body' and 'soul', in a metaphor reminiscent of Cartesian mind-body dualism: "entwined," and yet also "throwing control back and forth":

The EXEC evolved into more than a space-saving device, and game programs on cartridges became deeply entwined with it. “Strictly speaking, the EXEC is like a body without a soul,” Rolfe said. In this metaphor, the cartridge is the soul bringing the EXEC to life, while the EXEC is the body of processes that carry out the soul’s desires. This dance between the EXEC and cartridge code is clear when swinging one’s bat in Major League Baseball. The EXEC handles much of the work, first by calling the BATSWING routine contained on the cartridge ROM:

CMP .UP,R1 ;IS THIS COMMAND FROM UP PLAYER? BNZ RETINS ;IGNORE IT IF NOT MOV #NOKEYDSP,R0 ;PREVENT FURTHER SWINGING MOV R0,.KEYDSP ;BY NOT LISTENING TO KEYPAD ANYMORE CALL S.SWING ;BAT SWING SOUND MOV .BATRUP,R0 ;GET OBJECT NUMBER OF BATTER CALL TOOBJ ;GET DATA BASE ADD #.OBJSEQ,R1 ;WANT TO START SEQUENCINGThis is assembly language code from the Major League Baseball cartridge, with CPU instructions on the left. The text after the semicolons are non-executable comments left by Rolfe to describe what the code is doing. Since this is a two-player game, the BATSWING routine checks to see if the button press came from the player at bat, branching away from the routine if not (BNZ means “branch away if the result of the compare, CMP, is not zero”). The code changes the EXEC’s .KEYDSP variable (the key dispatch) to switch off the keypress interaction on the hand controllers. This prevents you from swinging twice. Then the code triggers the bat swing sound, a process that also uses the EXEC. BATSWING uses another EXEC routine called TOOBJ to retrieve the moving object of the batter and manipulate its animation sequence (using .OBJSEQ, another variable used by the EXEC). This starts the batter’s swinging animation, which is also handled by the EXEC. Then, if the videogame code on the cartridge determines that you hit the ball, the EXEC handles its movement. The EXEC code and the videogame cartridge code are thus constantly throwing control back and forth, like two kids playing catch

Notice that the play logic of the prototypical 20th-century American sport of baseball here is aligned with the logic of the Major League Baseball cartridge for Intellivision, That logic is constituted by e.g. the BATSWING routine and its code snippet, and that the 'soul' of the Baseball player's desire (to swing the bat) is embodied by the Intellivision's EXEC operating system, with Baseball a kind of ur-program or prototypical program against which the constituting logic EXEC against. For the authors co-constitution is actualized during code execution in a way that aligns, once again, with part of the cultural logic of a baseball: "throwing control back and forth, like two kids playing catch."

This suggests many potential entry points into the intellivision and its cartridge, OS, and development code, whether from broad contexts such as business culture or the history and philosophy of sport (and foundations of game studies) or from a single line of CP1610 assembly.

-- Jeremy Douglass, CCSWG 2026

For Discussion:

- What is the relationship of Intellivision code to the role of code in culture?

- How do the EXEC OS and Baseball cartridge and relate to the body/soul concept?

- What is interesting about these code examples and their platform today through the lens of software engineering and computer science, the history of computation, or cultural studies?

- How do the interrelationships of code work across various levels of abstraction (routine, library, operating system, CPU instruction set, hardware...)?

- What are the methodological interrelationships of "platform studies" to "code studies" in these examples?

Comments

(From Tom Boellstorff) Wow—thank you so much, Jeremy, for this thoughtful and insightful introduction to our book and these discussion questions! We’ll give folks some time to look all this over and comment, and will be excited to respond and join in—there is a possibility we could add some additional cool code if the discussion goes in that direction! 😎👍!

Thanks so much Jeremy for starting up a thread on our book and particularly pointing to chapter 5, which isn’t a chapter we often discuss since we often are not talking to people that are super interested in technical details.

In Chapter 5 we really had two overarching goals.

First, we wanted to offer a different way of understanding a “platform” as a multilayered structure (more like a ladder with multiple rungs) which could support engagement at different levels of depth and expertise. Thus, at a low level, Intellivision hardware contained the STIC (Standard Television Interface Chip) and the CPU1610. Then, above that, the EXEC was an onboard collection of code libraries and structures for games (which some call the first onboard Operating System for a game console); it significantly eased programming because it hid the hardware, allowing access to it in particular ways, while abstracting the hardware’s more complex functioning. Assembly game code that went onto the cartridges was really a mix of data for graphics, data processing using the CP1610, and calls to the EXEC operating system which was contained on ROMs within the console. The BATSWING example was a simple way for us to show how the code written by Intellivision game programmers and stored on game cartridges was heavily reliant on the libraries and affordances offered by the EXEC. The EXEC offered a structure for game programs and ways to access and manipulate the graphics objects defined by hardware (the body as Rolfe put it) while the game cartridge code and logic (soul) brought this body to life.

Second, we wanted to show that the Intellivision hardware architecture and software architecture was built to ease game programming (which had significant social ramifications for the kinds of people Mattel Electronics hired to create and design games). Programmers could become experts in the STIC and hardware if they wanted to (and even bypass the EXEC) or largely ignore the hardware and use the EXEC and its structures.

Looking at the BATSWING code above makes little sense unless one knows what the EXEC does and how it works. BATSWING basically begins an animation sequence of a batter swinging a bat. The EXEC operating system handles this. The Baseball game cartridge contains data for 8 animation frames that depict an 8-bit player graphic swinging a bat when they are sequenced quickly. These are loaded into the Graphics RAM of the Intellivision platform when the Baseball game cartridge initializes. The cartridge also tells the EXEC how to define the sequence of these frames, what address to start grabbing image data from, how fast to sequence from one image to the next: this information is contained in the 16-bit #.OBJSEQ word you see referenced at the end of the BATSWING code. ![]

If one looks deeper into the Baseball code, maybe it becomes a bit more interesting, for example, when pitched ball is hit or not. This SWING code is triggered when the ball arrives at a predefined location traveling towards home plate and the player has swung.

Here again, the EXEC's #.OBJSEQ (line 9) is used to extract the frame number of the animation sequence (0-7) when the ball is at the hit position. If the frame is 2-6 it’s a hit, otherwise not (as seen towards the end of the code snippet). While the Intellivision could perform object collision/interaction, it wasn’t needed. There’s no bat graphics/pixels hitting or contacting ball graphics/pixels. While we didn’t write about this in the book, there might be something to say in terms of the famed Magnavox patents (that also were used against Intellivision), and ideas of object coincidence, collision, hit symbols, etc.. ![]

Regardless, for anyone interested in seeing a simpler Intellivision program that leverages the EXEC to check out the original code for "Trivia" (called “Killer Bees”) which David Rolfe programmed sometime at the beginning of 1978. (Rolfe programmed both the EXEC Operating System and the Intellivision Baseball game simultaneously). We talk about "Trivia" in chapter 5, and this trainer code was used to demonstrate how effective the EXEC operating system was because one could create a simple interactive “game” and put it up on the TV with a small amount of code (a tantalizing prospect back in the day when ROM was expensive). If a small amount of code using the onboard EXEC could get a “man” running around the TV screen and interacting with an object, then 4K game ROMs could create some pretty complex games (a highlight of Intellivision’s legacy when compared to Atari).

The "Trivia" code is making a lot of use of the EXEC (which is behind the scenes here), but one can see a game structure emerging, with initialization, title screen display, control of the “running man” (CTRL), interaction with the edges of the screen, interaction with an object (HITMINE), and ROM and RAM databases at the end which populate the EXEC with data and information for the 8 moving objects that the Intellivision hardware defines. If you are curious, you can see a video of this "Trivia" program in action on an AtariAge post (it’s the first video). The “Trivia” program had many technical and social ramifications for Intellivision game development because programmers were often given this program (or later variations of it) to develop their first games and learn how to use the EXEC operating system. Thus, many games contain vestiges of this code or began from here. Moreover, Rolfe’s post of the Trivia code from 1999 declares, “Yes, it looks like gibberish now. Consider this as a primitive experiment in object-oriented programming... ” which is also something we didn’t write about in the book, but which we found interesting….

” which is also something we didn’t write about in the book, but which we found interesting….

This book is such an accomplishment! Let me take my turn at bat.

I want to pause on the "ladder with multiple rungs" image. That distinction separates out the layers, but this example shows how a code reading requires contact with multiple rungs at the same time, like a person climbing up or down a ladder. The key rungs are hardware, EXEC, and cartridge code. Although I like to also think of another version of the ladder: logic, state, and display.

There's a curious part of of the code excerpted here where the strike zone expands once the person swings. Or to be more precise, while the swinging animation is playing the strike zoon expands.

What's even more interesting to me is that the frame of the animation sequence is crucial to determining if there's a hit or not:

So the 8 states (0, 1-7 swing) are playing while the ball continues to move horizontally:

Notice how critical the frame number is here?

Frames 2-6 are contact frames. The others (1 and 7) are misses (you can't hit the ball in these states).

So the 8 states of the animation sequence (the body) determine the game state (the soul). The moment you press the button, the strike zone expands from 6 to 10 pixels. This acts as a punishment for swinging on the early side.

Put another way:

EXEC's animation sequencing is key here. Swinging = animation sequence ≠ 0. EXEC's 60Hz animation sequencer is not just displaying the results, it's governing when decisions can be made. Once you press the button, you're committed to marching through those states at 60HZ, no checking your swing, no adjustments.

As programmer Rolfe described it, "The EXEC code and the videogame cartridge code are thus constantly throwing control back and forth, like two kids playing catch." The batting code shows the back and forth: the cartridge tells EXEC to start the animation sequence, EXEC cycles through frames, and the cartridge reads those frame numbers to determine gameplay outcomes. Neither layer can function without the other. You need both kids to play catch.

Following the other ladder model, the animation frames are not merely display but the game state itself. Frame number links the two.

As a result, the player is better off waiting to swing as long as possible. And hitting the ball has more to do with understanding the timing of the swing animation than sports knowledge. So this becomes a rhythm game, more about awareness of time than space.

And so by looking at the code we can see that the game rewards patience. This isn't baseball so much as code becoming a gameplay philosophy.

Thanks for this Mark! It brought up a lot of thoughts in terms of critical code studies methodologies, game code, and analysis. I love the close attention you are giving to the code in terms of its impact on gameplay. We ran into this often when examining Intellivision code—how a deeper knowledge of the code could certainly translate into informed play styles. The “hit” based on the animation sequence was a surprise to us in terms of how a “hit” was determined. As you start doing with the expanded strike zone, one could continue tracing the code (beyond what we have here of course) to see how ball direction and speed are determined after the hit, foul balls, homeruns, etc.. Or we could examine the different pitch options and their impact on ball movement and interaction with the strike zone. As you start doing in your response, one could trace the entire logical apparatus around the ball as it goes through the game system. One could theorycraft the game, with this additional knowledge. We found similar moments in the code of other games like BurgerTime (player movement), Astrosmash (hidden dynamic difficulty adjustment), Utopia (emergent strategies because of how the movement code was written), and the list could go on. Most of these were not mentioned in the manuals, or obliquely. Methodologically, I am not sure this is critical code studies unless we read the “critical” in terms of a “critical state” of transformation (perhaps like Bruno Latour does in “Why Has Critique Run Out of Steam?”). (E.g. What points in the code indicate crucial moments where an interesting transformation emerges?)

That said, I loved your reading of code/gameplay, and pointing out that the game becomes a rhythm game, and thinking in terms of the code and how it behaves through Rolfe’s metaphors; like you and Jeremy point out, the body/mind comment does begin to make us look at the code and Intellivision’s architecture through a philosophical lens, but I need to think more about this….

I was also really interested in how you take the ladder metaphor we use in a different direction (logic, state, display) and then relate the ladder idea to the practice of “code reading”. Never thought of that. We were thinking of programmers at the time and their labor, not people analyzing the code later on. It’s true, as you say, that “code reading” Intellivision games “requires contact with multiple rungs at the same time.” The EXEC/Cartridge game of catch illustrates that. This could mean that “code reading” is a particular kind of labor that requires multifaceted points of entry and expertise. I am sure you and others in the community discuss things like this often, but does “code reading” in the context of platforms require a wholistic knowledge of a system, and levels of expertise that span all levels of a platform ladder? Does “code reading” require that someone be an expert and can go up and down the ladder (like Rolfe had to do)? In contrast, can critical code studies operate on different rungs of the ladder, so to speak? Perhaps it depends on the context. The ladder metaphor and our work on Intellivision’s platform and programming culture(s) was always concerned with the social, pushing back a bit on the expert “one-programmer, one-game” idea of early game development; the idea of platform cultures articulates an array of situated knowledges and rungs of support for programmers at different levels of expertise. In the same way it seems that a robust “code reading” likely requires the kind of collective structures we see here in the CCSWG (and also in collective books you and others have written in this space in the past). In any case, maybe this is a question more about the relationship between platform studies and critical code studies…How much does an individual need to know about the entire platform to analyze it’s code?

Echoing Braxton’s comments—what a fascinating post, Mark! Just adding a couple thoughts…

Your summary “this isn’t baseball so much as code becoming a gameplay philosophy” is such a nice way of putting all this—that in the case of Intellivision’s Major League Baseball, “hitting the ball has more to do with understanding the timing of the swing animation than sports knowledge.” As Braxton said, Rolfe (and us) were using the “ladder” metaphor to refer to game design, but you could use it to think about relationships between hardware, EXEC, and cartridge code (and also logic, state, and display). The only downside to the metaphor here is there are forms of simultaneity here (like the strike zone expanding when you swing).

It would be fun to think about, and compare, these kinds of “gameplay philosophies” when they are more intentional versus more emergent. This example from Baseball is, as you note, very much on the “intentional” side—the way in which swinging the bat is a “rhythm game, more about awareness of time than space” is intentionally coded into the game. Compare that with our discussion of the world-simulation game Utopia (which we discuss in Chapter 7) of Intellivision. In that game, “sandbars” that restrict the movement of player boats were an unintended side effect of Don Daglow’s coding to ensure that boats did not end up on land. The naming of this restricted movement as “sandbars” originated in a Quality Assurance (QA) report by the tester Pat Burnell. Yet as we note, this had consequences for gameplay—you can trap and sink your opponent’s boats (using your PT boat) using these sandbars. It’s what we might term an emergent philosophy that turns a world-building game into a different kind of chasing game—a little taste of Pac-Man perhaps!

Thanks again for these really insightful and generative comments!