Howdy, Stranger!

It looks like you're new here. If you want to get involved, click one of these buttons!

Categories

In this Discussion

Rivulet: calligraphic code inspired by natural language

In Rivulet, code is inscribed in strands, box-drawing characters that combine into continuous lines. Strands are organized into glyphs, units of code that resemble paragraphs more than blocks of code. They are usually tightly packed; the aesthetic of Rivulet is inspired by the satisfying compactness of mazes, Anni Albers's Meanders series, and space-filling algorithms. Semantically, a glyph is a set of strands that execute together. But they are also syntactic units, in that not all strands can appear together in the same glyph because they might block each other in how they flow through the glyph's space.

Rivulet is a language inspired by natural language; it has an internal logic, a coherence, but with no rational explanation. Rivulet relates to the Week 3 discussions, as it's part of the Source Code Exhbition, but it's also in Forty-Four Esolangs, discussed in Week 1.

It takes a while to understand the full syntax of Rivulet, but I want to focus here on only two aspects: first, the way that line numbers work in the language, and second in how "zero strands" are written.

Here is a single Rivulet glyph:

1 ╵──╮───╮╶╮

2 ╰─╯╰──╯ │

3 ──╮ │

5 ╰──╯ ╷

And here is pseudo-code for the glyph, which can be generated by running the interpreter with the -v for verbose option:

list2[0] += 0

list2[1] += 1

list1[0] += -16

The glyph begins and ends with glyph markers: ╵ and ╷. Each strand begins with a hook pointing up or left, which marks its beginning (strands without hooks or with hooks pointing in other directions are used for other types of strands not considered here). Each unit it moves to the right adds the value of that line number, and each movement to the left subtracts it. The line number it appears on marks a list element it is writing to; by default, it is an add-assignment (+=). First from the left is the strand beginning on line 2, which gives us list2[0] += 0. This is called a zero strand, and it has no effect on that list element, but is there so that the second strand beginning on line 2 can write to list element 1, for list2[1] += 1. Finally, it reads the third strand (reading from left to right), which assigns to list1. It moves to the left twice on line 5, subtracting 10, and then twice on line 3, giving us -16.

You may notice there is no line 4. In Rivulet, line numbers are successive primes. Line numbers don't need to appear in the code, but can be included as reference, as the Rivulet interpreter ignores all non-box-drawing characters. They also reset with each glyph. Why prime numbers? The compactness of the glyphs need numbers that grow faster than a linear progression, and less than exponential growth, so that one can represent large numbers without making the glyphs very large. Prime numbers hint at a deeper meaning, but this is primarily an aesthetic decision. I imagined what a programming language might look like had it developed like a natural language, with conventions that have an internal consistency, but no rational explanation.

The zero strand is needed often, to allow writing to list elements beyond zero. There are many ways to write them. Here is a set of zero cells writing to list1. Each of these is equivalent:

1 ╵╰──╮╰───╮╶╮

2 ─╯ │ │

3 ─╯ ╰──╮

5 ╭────╯

7 ╰── ╷

Running -v gives us this pseudo-code:

list1[0] += 0

list1[1] += 0

list1[2] += 0

But more specifically, the flow is:

list1[0] += (2*1) + (-1*2)

list1[1] += (3*1) + (-1*3)

list1[2] += (2*3) + (-5*5) + (-3*7)

Writing to list2, these are all zero strands:

1 ╵╭─╮ ──╮

2 │╶╯╶╮╰────╮╰─╯╶╮

3 ╰──╮╰─╮ ╭─╯ ╭──╯

5 ─╯ │─╯ ╰────╮

7 ╭───╯ ──╯

11 ╰────╮

13 ──╯ ╷

list2[0] += (-1*1) + (2*3) + (-1*5)

list2[1] += (1*3) + (-3*7) + (4*11) + (-2*13)

list2[2] += (4*2) + (-1*3) + (-1*5)

list2[3] += (1*2) + (-2*1)

list2[4] += (-2*3) + (4*5) + (-2*7)

Any one of these can be used as a zero strand for list2. We would draw a strand -- one of these or another -- which gets out of the way of other strands we want to appear in the same glyph. Writing Rivulet is often a re-working of existing strands in order to add others to the glyph.

The Rivulet interpreter also includes an svg generator, which draws the strands as complete lines and colors them so that related strands are the same color (we have no strands that refer to each other here, since we are only dealing with the simplest kind of strand, that used for add-assignment):

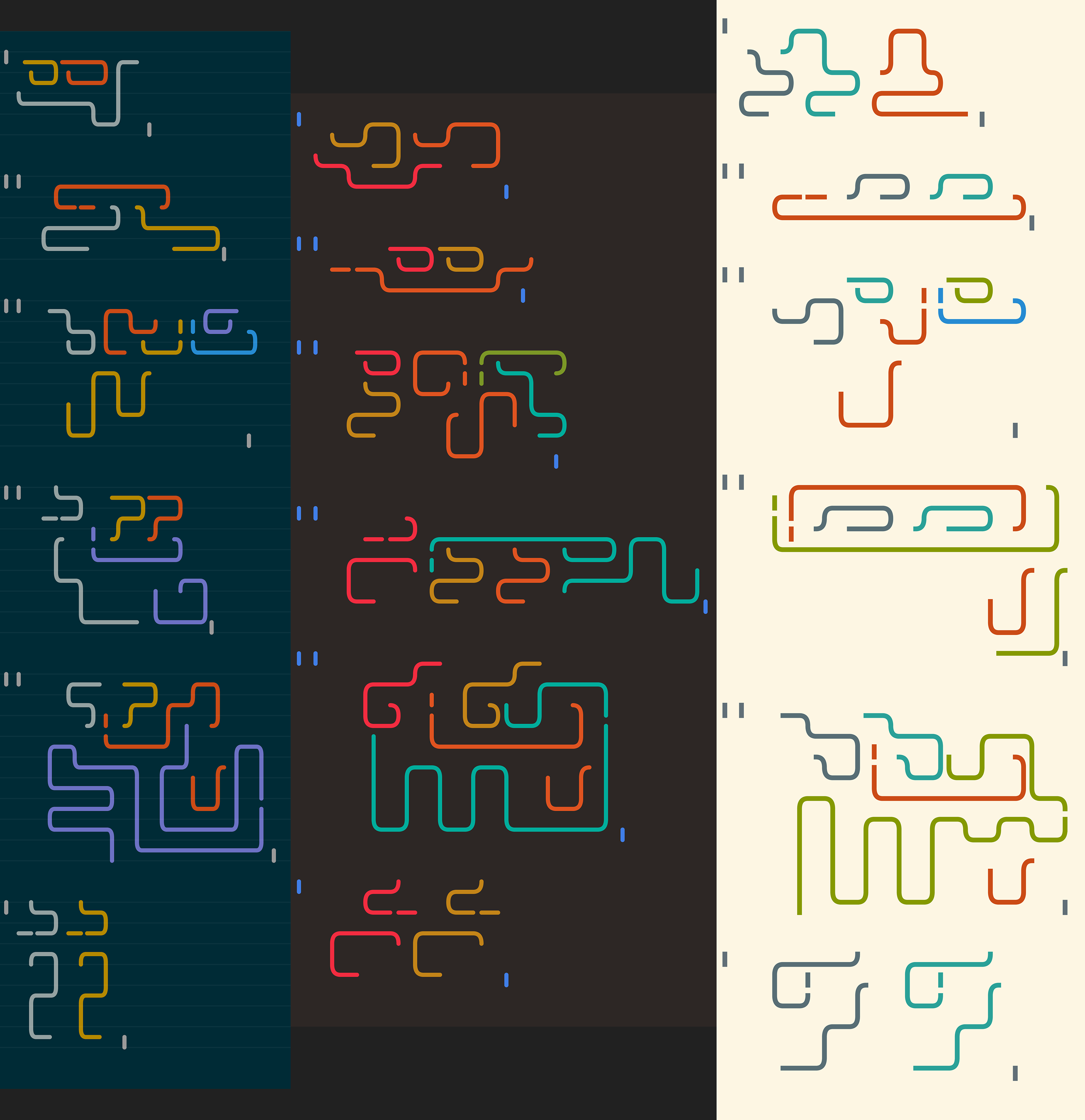

And here is a complete Fibonacci program, using the same algorithm, the same "code," represented with strands that move differently through the space (and generated with different color themes):

More on Rivulet

- Rivulet interpreter (github)

- The original tutorial

- Intro to Rivulet by Jo Wood

- Syntax reference

- Hacker News discussion

Comments

Thanks for this detailed walkthrough, Daniel. Rivulet sits within the exhibition's "Source Code as Cultural Artifact" section, alongside pieces like the Wenyan language and the obfuscated C. But where Wenyan challenges the linguistic hegemony of English and the obfuscated C plays with the tension between human and machine readability, Rivulet does something different: it questions why programming became textual at all. The dominance of text wasn't purely logical — it emerged from material constraints like Teletype machines, punch cards, and the Unix culture that grew around line-based editors and pipes. Rivulet proposes an alternative lineage, one rooted in calligraphy and spatial composition, and in doing so helps visitors see that the paradigm we inherited was historically contingent, not inevitable.

Your description of writing Rivulet as "re-working existing strands to add others" reminds me of early programming constraints, where coders had to hold the entire machine state in mind. Rivulet seems to demand a similar totality of awareness, but spatial rather than temporal. It also makes me think of figures like Paul Graham or Maciej Ceglowski, programmers who came from painting and bring a visual sensibility to their work. Does Rivulet suggest something about what programming might owe to ways of thinking we don't usually associate with code?

@Titaÿna

I love the framing of Rivulet as grounded in an "alternative lineage" of "spatial composition." The word 'lineage' seems particularly serendipitous here because it is a lineage based on the expressive use of lines.

One part of this 'lineage' would surely be patch-cord based programming. We could think of the Enigma machine and its plugboards in the 1930s and 40s, and the corresponding Bletchley Park Bombe for decoding them with its own configuration of connecting lines (and historical recreations with their own cable-connected patch panels). There are even simulations like the Virtual Turing-Welchman Bombe that let you walk up to the machine and program it virtually connecting different parts with virtual cords in a 3D first-person walking simulator.

In more general purpose computing, ENIAC was also patch-based:

...and this word "patch" also descends through the history of computer music (e.g. the Moog synthesizer, also patch-cord programmable) to the "patcher" programming languages such as Max/MSP and PD (Pure Data), where each code patch is a tiny diagram.

Of course, Rivulet is not a patch-based language, in the sense that the shapes of the cords in an Enigma / ENIAC / Moog / Pure Data configuration do not have expressive shapes -- they are abstractly diagrammatic means to connect point A to point B, while in Rivulet, the journey is the destination (or perhaps the meander is the message/massage). In that sense it might have an alternate lineage in some of the two-dimensional esolangs or Befunge-like fungeoids.