Howdy, Stranger!

It looks like you're new here. If you want to get involved, click one of these buttons!

Categories

In this Discussion

Fictional Code - Jurassic Park (1990)

Title: Jurassic Park

Author: Michael Crichton

Language: (Fictional)

Year of development: 1990

Code Snippet:

curv = GetHandl {ssm.dt} tempRgn {itm.dd2}.

curh = GetHandl {ssd.itli} tempRgn2 {itm.dd4}.

on DrawMeter(!gN) set shp-val.obi to lim(Val{d})-Xval.

if ValidMeter(mH) (**mH).MeterVis return.

if Meterband](vGT) ((DrawBack(tY)) return.

limitDat.4 = maxbits (%33) to {limit 04} set on.

limitDat.5 = setzero, setfive, 0 {limit .2-var(szb)}.

on whte-rbt.obi call link.sst {security, perimeter} set to off.

Vertrange={maxrange+setlim} tempVgn(fdn-&bb+$404).

Horrange={maxRange-setlim/2} tempHgn(fdn-&dd+$105). void

DrawMeter send-screen.obi print.

Context:

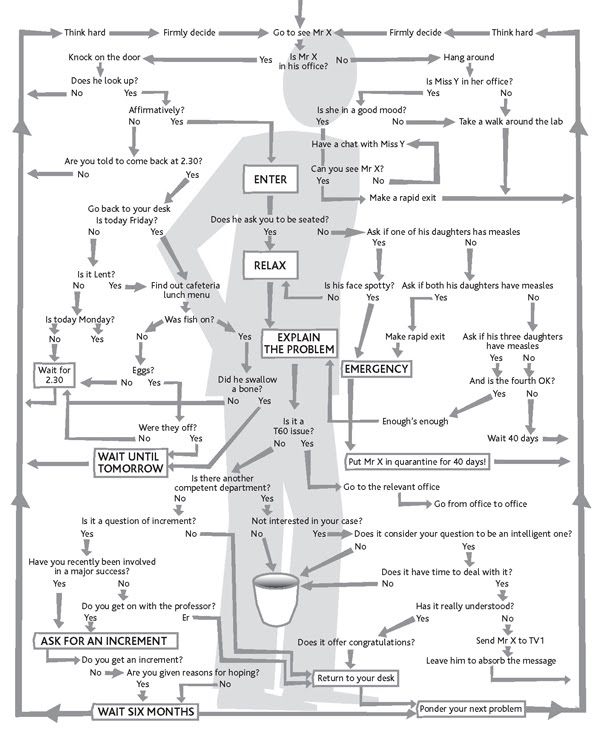

In a novel, computer code is rarely shown. Where code features in a plot, it is most often alluded to without printing the code itself, such as in hacker sequences of the sort found in Neal Stephenson or William Gibson novels. The reader of a novel is not usually expected to be conversant in the language of code. There have been a few works of literature inspired by computer code, such Georges Perec's The Art of Asking Your Boss for a Raise, where the whole short novel is styled as the output of following an algorithm represented by this flowchart:

Where code does appear in a novel, we might expect it to be maximally readable, like the BASIC code in Gabrielle Zevin's Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow (2022):

10 READY

20 FOR X = 1 TO 100

30 PRINT “I’M SORRY, SAM ACHILLES MASUR”

40 NEXT X

50 PRINT “PLEASE PLEASE PLEASE FORGIVE ME. LOVE, YOUR FRIEND SADIE MIRANDA GREEN”

60 NEXT X

70 PRINT “DO YOU FORGIVE ME?”

80 NEXT X

90 PRINT “Y OR N”

100 NEXT X

110 LET A = GET CHAR()

120 IF A = “Y” OR A = “N” THEN GOTO 130

130 IF A = “N” THEN 20

140 IF A = “Y” THEN 150

150 END PROGRAM

Here this code is syntactically flawed to show the beginner status of the programmer, and the function of the code is explained in the next passage for the readers who cannot follow along.

The novel Jurassic Park was written by a former programmer, Michael Crichton. He made the dinosaur park's computer system a central feature of his novel, even including images of its GUI. He took a different approach to referring to code to other authors: the code was shown and it was deliberately incomprehensible. In the snippet quoted above, only one line of the code is meant to be sensible to the reader and is explained in the dialogue immediately before it is displayed:

“It’s marked as an object,” Wu said. In computer terminology, an “object” was a block of code that could be moved around and used, the way you might move a chair in a room. An object might be a set of commands to draw a picture, or to refresh the screen, or to perform a certain calculation.

“Let’s see where it is in the code,” Arnold said. “Maybe we can figure out what it does.” He went to the program utilities and typed:

FIND WHTE_RBT.OBJ

The computer flashed back:

OBJECT NOT FOUND IN LIBRARIES

“It doesn’t exist,” Arnold said.

“Then search the code listing,” Wu said.

Arnold typed:

FIND/LISTINGS: WHTE_RBT.OBJ

The screen scrolled rapidly, the lines of code blurring as they swept past. It continued this way for almost a minute, and then abruptly stopped.

“There it is,” Wu said. “It’s not an object, it’s a command.”

The screen showed an arrow pointing to a single line of code:

What follows is designed to be an opaque wall of computer code. If you know what to look for, you might understand some parts as functions (DrawMeter), and you might guess some of it may be to do with measuring something (there is a vertical and horizontal range), perhaps for showing on the screen ("send-screen.obi print"). The function of printing the sequence of code in the novel is to show that there is irrelevant code that hides a "trap door":

“Son of a bitch,” Arnold said.

Wu shook his head. “It isn’t a bug in the code at all.”

“No,” Arnold said. “It’s a trap door. The fat bastard put in what looked like an object call, but it’s actually a command that links the security and perimeter systems and then turns them off. Gives him complete access to every place in the park.”

Just as Arnold skim reads the code, dismissing the surrounding lines as irrelevant in his search, so to does the reader. The incomprehensibility of the code is itself part of the literary technique of deploying it. This deliberate opacity can be seen clearly in the French translation of the novel. In the 1992 edition, translated by Patrick Berthon, (pg. 260), the commands and error messages are translated into French, like so:

RECHERCHE WHTE-RBT.OBJ

Le message suivant s'afficha:

OBJET NON TROUVÉ DANS BIBLIOTHÈQUES

Whereas the code (including the "white rabbit" object itself) appears identically, with no localisation. When code appears two chapter later, it has the same superficial appearance (though without the full stops). There its appearance is to show the code with and without a few lines of self-deleting code. These lines are written to be intelligible:

on fini.obj call link.sst [security, perimeter] set to on

on fini.obj set link.sst [security, perimeter] restore

on fini.obj delete line rf white-rbt.obj, fini.obj

The code restores the security perimeter and then deletes itself and all mention of the white rabbit trap door. We can imagine a language such that this code could believably execute, whereas that is harder to do with the deliberately nonsensical code that surrounds it. Here, the surrounding lack of sense heightens the readability of the section of code the reader is led to understand.

Questions:

- Are there other examples of fictional code that take a different approach or is deployed for a different effect?

- Does a segment of code add or remove from the immersive quality of a novel? Does it matter if the code really could or couldn't compile?

- Are there some underexplored literary uses that code could be put to?

Comments

This is really fun! Although not quite code, Peter Watts’s Blindsight includes a very cool technical explanation of the (anti)role of consciousness, and of why vampires are afraid of crosses. To explain these (and how they are related!) would ruin this wonderful book for you, so I won’t, but also I don’t feel like spending an hour writing it up, so I got Gemini to do it for me. Be forewarned: SPOILER ALTERT: https://g.co/gemini/share/5fbcaa42fa2c

By way of building on past work, you may want to check out this thread from our 2018 Critical Code Studies Working Group, launched by @lizlosh : Gender and Programming Culture: Representing Code in Movies with Female Programmers. And if I recall, there was at least one earlier conversation, possibly in 2010!

In a novel about the recovery and hacking of genetic code, I like the potential thematic synergies. It's been a long time since I read it, and now I'm wondering if Crichton shared snippets of DNA sequences, too? Was the splicing of the frog DNA also a "trap door" allowing for reproduction?

With rising code literacy, I have to imagine we'll see all sorts of in-text snippets in the future of fiction, though I wonder if the rise of audiobooks has killed the chance that this kind of immersion tactic will be used in popular novels.

Hallucinate This! (which is also featured in Output) contains a letter of complaint about unwanted asvances from Flow the waitress to the Code Chef in python. I am not sure if this counts as fictional code or early (2023) vibe coding. Here is the code and the prompt.

Here is the prompt:

Re: "Are there other examples of fictional code that take a different approach or is deployed for a different effect?"

Douglas Coupland's Microserfs (1995) and JPod (2006). I recall (again, office) that Microserfs incorporates mainly C-like / C++ code. The opaque wall of code is often also scrambled-code (related to codework. In the Jurrasic Park example, for the sake of the fiction it is important that the fictional code is reasonable looking and compiles. With surrealist / scrambled / codework code that isn't always clear even within the diagesis. Also, on the page level, the text may be an OCR nightmare. I tried to scan my hardcover of Microserfs many years ago and I recall giving up fairly quickly. Here is a note that I just found online from one aggrieved scanner:

The "Micro Adventure" and "Magic Micro Adventure" series of game books (~1985) incorporated type-in BASIC programs that you used to resolve plot points and navigate the story structure. "Arcade Explorers" did this as well, but I believe that you accumulated code over the course of the story, resulting in a long runnable program at the end. I have a few of the "Micro" books in my office, but I believe that the code was often (but not always) diegetic, in the story world, and not a paratext. This is an interesting midway point between a type-in microcomputer program like our discussion of POET and a fictional "output" like the Jurassic Park example.

Thank you for the intriguing books recommendations, @jshrager, @markcmarino and @jeremydouglass — my reading list grows ever longer.

Where film is a visual medium, it's fascinating to see code as part of the language of screen. Following the links in the other thread, there were a lot of examples. Jurassic Park of course was also a film and in the film you briefly see the code and also there is the extensive scenes where the older niece, Lex, uses her computer skills to reboot the computer system: "It's a UNIX system, I know this!". This is a change from the books where her brother Timmy uses the computer, and Lex plays a more passive role. In the story, navigating the computer system is as much a show of skill and knowledge as evading the dinosaurs.

@Zach_Mann, what a great parallel! And yes, large segments of genetic code are reproduced in the novel in much the same way as the computer code.

Thanks for including Georges Perec's The Art of Asking Your Boss for a Raise!

At one point a computer-mediated version was online -- I think on the book publisher Verso’s site -- and I used this version to illustrate flow charts in my classes. I can no longer find this version, but the Verso edition, translated by David Bellos, is perfect. Bellos gives the history of this work in his introduction and then follows the history with the 80 -page-long one sentence that Perec wrote from the flow chart created by Jacques Perriaud, which (shown in your intro) is printed inside the covers of this artist book like edition. It is still available from Verso for only 14.95 probably at

https://www.versobooks.com/products/2182-the-art-of-asking-your-boss-for-a-raise

I've enjoyed the short novel but I wasn't aware of the virtual implementation of the flowchart, so thank you for that. I've managed to find an archived version of it on the waybackmachine.

For a less exalted information art example see TidyFIle created for Bad Information and available in a Bad Information search at

https://people.well.com/user/jmalloy/badinfo/newgod.html

Bad Information – created on The WELL in 1986, is receiving current interest due to AI issues, and part of the search page at the above url will be on the cover of an Italian book currently in press. I had overall permission but was concerned about first Director of The WELL Mathew McCure’s post because he has since held some high power jobs, so I checked with him and he said he was retired so why not. Also on this output page is a contribution from , The first director of The WELL

Wow! The archived interactive version of The Art of Asking Your Boss for a Raise! is actually working on the waybackmachine. Great news. Many thanks @JoeyJones

My pleasure! It's a neat visualisation.

I enjoyed looking through the Bad Information collection and the BASIC joke TidyFile code is a good example of the fictional-code-as-joke. I think with these, we don't really expect the code to compile (though perhaps this one would?), the point is to work through and imagine what it might do. It's reader-facing, rather than machine-facing. It's the same kind of humour as those joke music scores, which of course are more funny if you already know sheet music, and nobody expects to actually be performed:

Here's another example from Gnu.org:

Thanks for the String Quartet!

Re TidyFIle, the program does compile but it doesn’t actually do anything. That is why I wrote it to include in Bad Information. This issue now arises when students ask an AI System to write a program that does something or other and the resulting program runs without error but it doesn’t actually do what was asked.