Howdy, Stranger!

It looks like you're new here. If you want to get involved, click one of these buttons!

Categories

In this Discussion

Markdown: A Lightweight Markup Language (2004)

Author: John Gruber

Language: Markdown syntax specification; original implementation in Perl

Year: 2004

Source: Daring Fireball, https://daringfireball.net/projects/markdown/

Software/Hardware Requirements

Markdown is a plain text formatting syntax and a text-to-HTML conversion tool. The original implementation was a Perl script (Markdown.pl) that processed .md or .markdown files into HTML. Unlike Scribe, which required a PDP-10 and BLISS compiler, Markdown runs anywhere Perl runs, which by 2004 meant essentially any Unix-like system, including Mac OS X and Linux. The format itself requires no special software to write, only a text editor, and remains human-readable without processing.

Context

This code critique accompanies the Scribe code critique in Week 2. Where Scribe (1980) represents the emergence of structured document markup in academic computing, Markdown (2004) represents something like a return of the repressed, a deliberate simplification that prioritises human readability over formal rigour. Together, they bookend the "word processing parenthesis," the period of WYSIWYG dominance – and Markdown might be a signal that it is closing.

Markdown matters for three reasons. (1) Its syntax decisions have become infrastructural, shaping how millions of people write documentation, notes, and web content – it is also the (current) format crucial for powering the AI moment we are having in 2026. (2) Its licensing (or lack thereof) contrasts sharply with Scribe's commercialisation, representing a different political economy of software. (3) Its subsequent fragmentation into competing dialects (CommonMark, GitHub-Flavored Markdown, MultiMarkdown) raises questions about standardisation, power, and whose conventions become normalised.

Code

The Markdown Syntax

Markdown uses ASCII punctuation characters to indicate structure. Unlike Scribe's @ commands or HTML's angle brackets, Markdown syntax was designed to be "publishable as-is, as plain text, without looking like it's been marked up with tags or formatting instructions" (Gruber 2004).

Headers use hash marks:

# Heading 1

## Heading 2

### Heading 3

Emphasis uses asterisks or underscores:

*italic* or _italic_

**bold** or __bold__

Lists use dashes, asterisks, or numbers:

- Unordered item

- Another item

1. Ordered item

2. Another item

Links and images use brackets and parentheses:

[Link text](https://example.com)

Block quotations use the email convention of angle brackets:

> This is a quotation

> spanning multiple lines

Code is indicated by backticks (inline) or indentation (blocks):

Inline `code` here

Four-space indented code block

Design Philosophy

Gruber's specification emphasises readability over "parseability":

The overriding design goal for Markdown's formatting syntax is to make it as readable as possible. The idea is that a Markdown-formatted document should be publishable as-is, as plain text, without looking like it's been marked up with tags or formatting instructions.

This inverts the usual priority in markup language design. SGML, XML, and even Scribe prioritised unambiguous machine parsing. Markdown prioritises the human reader of the source file, accepting some parsing ambiguity as the cost.

The Perl Implementation

The original Markdown.pl is approximately 1,400 lines of Perl. It processes text through a series of regular expression substitutions, transforming Markdown syntax into HTML. The code is procedural rather than structured around a formal grammar, reflecting Markdown's origin as a practical tool rather than a formally specified language.

A representative excerpt shows the pattern:

sub _DoHeaders {

my $text = shift;

# Setext-style headers:

# Header 1

# ========

#

# Header 2

# --------

#

$text =~ s{ ^(.+)[ \t]*\n=+[ \t]*\n+ }{

"<h1>" . _RunSpanGamut($1) . "</h1>\n\n";

}egmx;

$text =~ s{ ^(.+)[ \t]*\n-+[ \t]*\n+ }{

"<h2>" . _RunSpanGamut($1) . "</h2>\n\n";

}egmx;

# atx-style headers:

# # Header 1

# ## Header 2

# ## Header 2 with closing hashes ##

# ...

# ###### Header 6

#

$text =~ s{

^(\#{1,6}) # $1 = string of #'s

[ \t]*

(.+?) # $2 = Header text

[ \t]*

\#* # optional closing #'s (not counted)

\n+

}{

my $h_level = length($1);

"<h$h_level>" . _RunSpanGamut($2) . "</h$h_level>\n\n";

}egmx;

return $text;

}

This code reveals several things. The use of Perl's extended regular expression syntax (/x modifier) allows readable formatting of complex patterns. The dual support for "Setext-style" (underlined) and "atx-style" (hash-prefixed) headers shows Markdown inheriting conventions from earlier plain text traditions. The regex-based approach, rather than a formal parser, explains both Markdown's flexibility and its parsing edge cases.

Provocations

On the politics of simplicity. Markdown's design prioritises ease of writing over formal specification. This has democratic implications, anyone can write Markdown without learning a complex syntax, but also creates problems. The original specification left many edge cases undefined, leading to the fragmentation problem that CommonMark later attempted to address. Is "simplicity" a neutral design value, or does it encode particular assumptions about users and use cases?

On plain text as ideology. The preference for plain text has deep roots in Unix culture and hacker ethics. But "plain" text is never simply plain. UTF-8 encoding, line ending conventions (LF vs CRLF), and character set assumptions are all contested terrains. The apparent simplicity of .md files conceals layers of standardisation and historical compromise. What would it mean to read plain text ideologically?

On licensing and the gift economy. Gruber released Markdown under a BSD-style license, essentially giving it away. Aaron Swartz, who contributed to the specification as a teenager, later became famous for his information-freedom activism and died in 2013 while facing federal prosecution for downloading academic articles. The contrast with Reid's sale of Scribe and insertion of time bombs could not be sharper. What do these different political economies of software reveal about the conditions under which technical infrastructure emerges?

On fragmentation and standardisation. Markdown's success created its own problems. GitHub-Flavored Markdown added tables, task lists, and syntax highlighting. MultiMarkdown added footnotes, citations, and metadata. CommonMark attempted to create an unambiguous specification. The format that solved HTML's complexity problem has reproduced complexity at another level. Who gets to decide what "Markdown" means?

On LLMs and markup. Large language models are trained on vast quantities of Markdown-formatted text from GitHub, documentation sites, and technical blogs. When we prompt an LLM to write, it typically produces Markdown. Does this training data bias encode particular assumptions about document structure? Whose conventions are being reproduced and naturalised through AI-mediated writing?

Resources

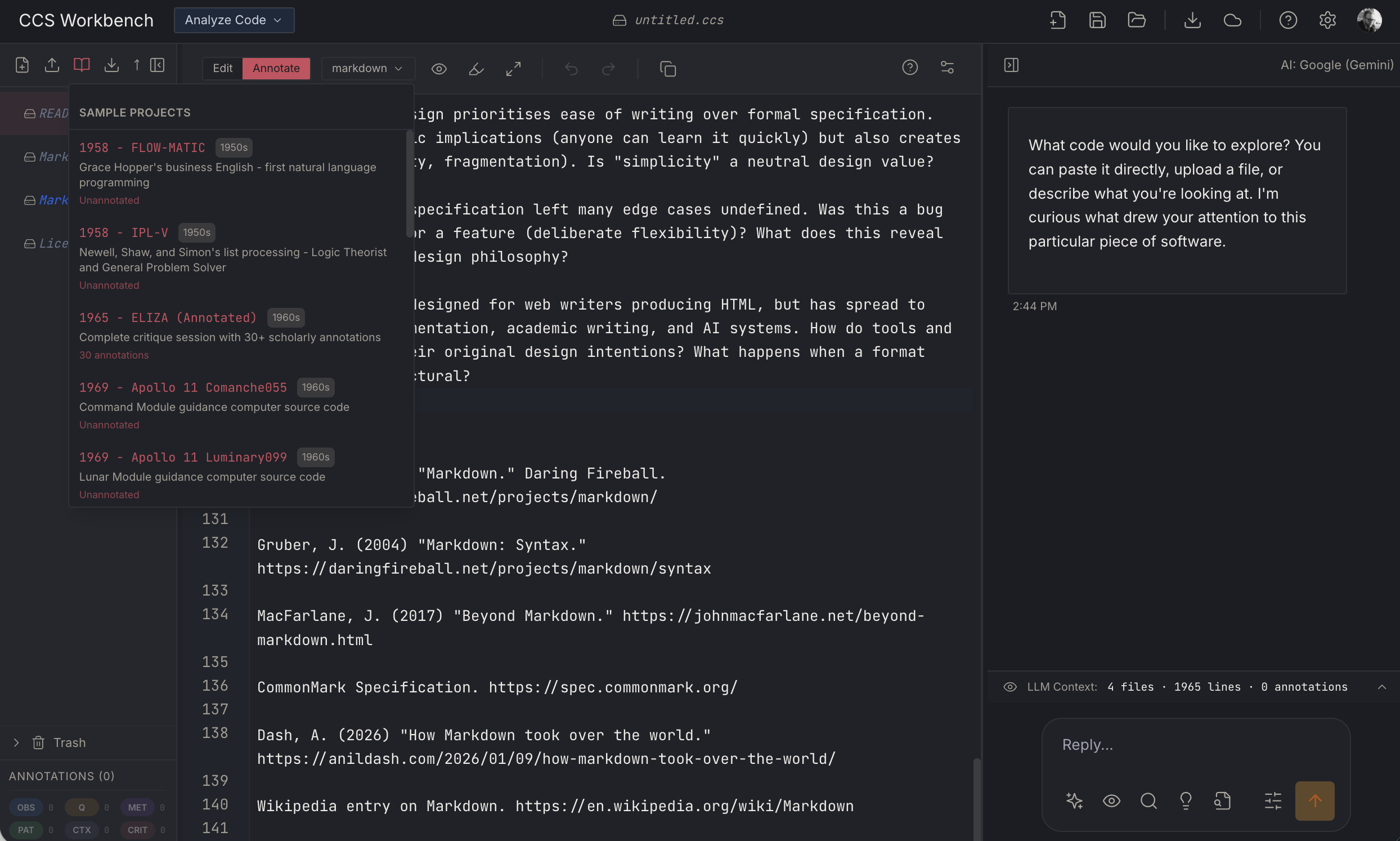

Markdown in the CCS workbench as a sample: https://ccs-wb.vercel.app/

Gruber, J. (2004) "Markdown." Daring Fireball. https://daringfireball.net/projects/markdown/

Gruber, J. (2004) "Markdown: Syntax." https://daringfireball.net/projects/markdown/syntax

Original Perl implementation: https![]() /daringfireball.net/projects/downloads/Markdown_1.0.1.zip

/daringfireball.net/projects/downloads/Markdown_1.0.1.zip

CommonMark specification: https://spec.commonmark.org/

MacFarlane, J. (2017) "Beyond Markdown." https://johnmacfarlane.net/beyond-markdown.html

Dash, A. (2026) "How Markdown took over the world." https://anildash.com/2026/01/09/how-markdown-took-over-the-world/

Wikipedia entry on Markdown: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Markdown

The Source Code

The original Markdown.pl (version 1.0.1, 2004) is available from Daring Fireball:

https://daringfireball.net/projects/downloads/Markdown_1.0.1.zip

Later implementations in other languages are numerous. Notable examples include:

- Python-Markdown: https://github.com/Python-Markdown/markdown

- marked (JavaScript): https://github.com/markedjs/marked

- commonmark.js (JavaScript reference implementation): https://github.com/commonmark/commonmark.js

- Pandoc (Haskell, converts between many formats): https://pandoc.org/

Questions About the Code

How does Markdown's syntax encode assumptions about document structure? The format handles paragraphs, headers, lists, links, emphasis, and code, but struggles with tables, footnotes, and metadata. What model of "documents" does this imply? What kinds of writing does Markdown make easy or difficult?

The original implementation uses regular expressions rather than a formal grammar. What are the consequences of this design choice? How does it relate to the parsing ambiguities that later motivated CommonMark?

Gruber explicitly borrowed conventions from email (blockquotes with

>), Usenet (emphasis with*), and earlier plain text formats (Setext headers). What does this genealogy reveal about the communities whose practices became infrastructural?Markdown was designed for web writers producing HTML. But it has spread far beyond that context, into note-taking, documentation, academic writing, and AI training data and AI output format. How do tools and formats exceed their original design intentions? What happens when a format becomes infrastructural?

The contrast between Markdown (given away, BSD license) and Scribe (sold, time-bombed) represents different political economies of software. What conditions enabled Gruber to give Markdown away? What does the gift economy of open source depend on that we might not see?

Comments

Just to keep the history correct: runoff predated scribe by over a decade, and begat, nroff, which was available available on every unix system (although unix was of course, less ubiquitous at the time). Both Runoff and the *roff set were free.

(As above, you'd have to go another 2 decades earlier to find the bookend you're looking for in (at least) Runoff....but...)

The period pf wysiwyg is not in any sense closing. We (as @davidmberry knows because he's a co-author it!) just had an entire book marked up by MIT Press entirely in Word. And IDEs for code are strongly wysiwyg with colors and indentation and all that. Indeed, part of the utility of markdown is exactly that's it's as close to wysiwyg as you can get if you don't have a fancy editor. In fact, that's where its notation came from!

(BTW, my 9th grade -- I think it was -- English teacher, Mr. Schlauch, used to take points off for using any sort of markings in our essays, like bold or underline or his favorite stalking horse god forbid we use an exclamation point! His point was that your words should carry all the meaning, and that annotations like those were just crutches. I recall asking him if we needed to use spaces -- I think I got kicked out of the room!)

My intuition is that wysiwyg as we know it is soon to be over. With an AI-powered "word processor" what you see may not be what you get. And what it is may be very different from what you are presented with as a visual metaphor. Power users may therefore have a mode (context engineering the word processor, perhaps) to specify this via markdown or another format. This then becomes less a word processor than a milieu in which one may write or co-write, without having to worry about formatting the document in quite the same way.