Howdy, Stranger!

It looks like you're new here. If you want to get involved, click one of these buttons!

Categories

In this Discussion

Treasure Hunt: Mabel Addis and the Sumerian Game

Nick's journey into David Ahl's collection got me thinking about Hamurabi, which Nick has also presented on in the past. I had never done much research into the game, but a quick search led me to the mentions of the inspiration: Mabel Addis' Sumerian Game, which is... dun, dun, duh! lost to history?

It looks like Andrea Contato has done quite a bit of work to reconstruct Humarabi from outputs that the Strong museum is in possession of. It's also built on the Wing report. But more importantly, he's written an exceptional book on the Sumerian Game, available online. I highly recommend Andrea's bookon the topic, The Sumerian Game, which I've just started reading. Looks like some excellent code archaeology.

Andrea eventually had to create his own version based on documentation, particularly printouts of gameplay. That reminds me a lot of what Team ELIZA had to do, though we at least had code to work with. Actually, there are other overlaps with ELIZA, as The Sumerian Game was developed in the mid 1960s, too.

I've invited Andrea to come discuss and share some of his code from his Steam game. Perhaps we could look at the code of this FOCAL version of the game, which as I understand it is the intermediary between The Sumerian Game and the BASIC version of Hamurabi. So the lineage is The Sumerian Game -> FOCAL Looks like FOCAL was more an adaptation than a port, but I'm still reading....

Here's some code.

01.10 T "HAMURABI: I BEG TO REPORT TO YOU,"!

01.20 T "IN YEAR ",Y," ",S," PEOPLE STARVED, ",A," CAME TO THE CITY."!

01.30 T "POPULATION IS NOW ",P,". THE CITY NOW OWNS ",L," ACRES."!

01.40 T "YOU HARVESTED ",H," BUSHELS PER ACRE. RATS ATE ",R," BUSHELS."!

01.50 T "YOU NOW HAVE ",S," BUSHELS IN STORE."!!

01.60 T "LAND IS TRADING AT ",V," BUSHELS PER ACRE."!

01.70 A "HOW MANY ACRES DO YOU WISH TO BUY? ",Q

01.80 I (Q) 1.7, 1.9, 1.9

01.90 S S=S-Q*V; S L=L+Q; D 2.1

Some approaches

- We can compare Contato's recreation later versions.

- This code is directly descended from the Sumerian Game, so we could do a heritage study?

- What do we know about Mabel Addis?

- What does any of this say about our fascination with ancient Sumer or our attempts to create a King Game - Kingdom-management resource sim?

Or we can use this for a discussion of the role of reconstruction projects in code archaeology and critical code studies!

Comments

Thank you for the interest you have shown in my work. First of all, I would like to clarify that there was not just one “Sumerian Game,” but that from the very beginning of the joint BOCES–IBM project there were actually two Sumerian Games: one developed at the Mohansic Laboratory by IBM technicians under the supervision of Bruse Moncreiff, and the other programmed at the BOCES center in Yorktown Heights.

The first one, which was called Sum9rx, was a prototype and, as far as we know, was already abandoned in 1964. The second one (called Suilxr), on the other hand, was modified several times and reprogrammed until the late 1960s, moving from Fortran to Assembly and finally to Coursewriter III.

These two versions shared some characteristics, including the narrative aspect (although it was less developed in Sum9rx) and the turn-based mechanism that required players to decide each turn how many resources to use to feed the city’s inhabitants, how much grain to store for future seasons, and how much to invest in planting. In all other respects they differed, including the mathematics and inventory management.

Sum9rx was only a prototype, created to see whether it could be fun. Moncreiff believed it was engaging enough to hold young players’ attention. Suilxr, instead, was improved and modified several times, with the addition of a slide projector and the creation of slides and audio recordings containing reports from the king’s advisers produced by the teachers involved in the project, who improvised as actors, artists, and photographers.

At least one copy of the game ended up in Canada, at the University of Calgary, where it was studied and reprogrammed in FOCAL to run on the PDP-8 time-sharing computer installed in the computer science laboratory. There, a DEC programmer—Douglas Dyment—became familiar with the educational program and reprogrammed it, adding features typical of games (such as the land market) that were not present in the original version. In doing so, he renamed it King of Sumeria, and later Hamurabi.

His version became very well known and was reprogrammed in BASIC by David Ahl, which further increased its dissemination. A copy of the FOCAL version reached Lexington High School, where a PDP-8 was available and where a very active and innovative teacher in the educational use of computers, Walter Koetke, was teaching. The students at the school played King of Sumeria, modifying it (in Bob Becker’s version). Among them, Jim Storer was so inspired by Dyment’s game that he created two new ones. The first, Lunar Lander, later became famous as the inspiration for Atari’s arcade game and many other computer games, while the second, Pollution Game, was a more ironic and dystopian version of King of Sumeria.

Drawing in part on Storer’s Pollution Game (which was originally programmed in BASIC), David Ahl modified his version of Hamurabi and published it in BASIC in 101 BASIC Computer Games.

The family tree below traces this intricate history, and by examining the output printouts (which I used to reconstruct versions whose source code has been lost) and the code listings of the surviving versions, the imprint left by the programmers who reworked these programs—modifying them, porting them to other languages, and drawing inspiration from them to create new games—is clearly visible.

@andreacontato So impressive all this work that has been done on this game. It ties in so fully with the work that Team ELIZA has been doing. In fact @jshrager has been trying to develop various taxonomies for discussing these sorts of family trees. Jeff, can you share some of it here.

So many parallels, including both ELIZA and the Sumerian Game being early programs that hobbyists wrote their own versions of.

Can you talk a bit about what making your version of the game for Steam taught you about the game or helped you understand about Mabel's work or other earlier versions?

Aha! Yes, quite so! The ancestry tracing that @andreacontato has done is brilliant. (And quite a lot of work!) The whole reason that I got re-interested in ELIZA was to take on this specific problem. Here's a sort of long proto-blog-post that I've been "writing" (and rewriting and rewriting!) for several months...on a project that I've literally been working on for decades! @markcmarino

Reconstructing Program Genealogies: An Update from the ELIZA Phylogeny Project

Jeff Shrager

December 2025

How I Got Here

Let me start with a confession: I've been obsessed with ELIZA for most of my life, though I didn't always know it. When I was 13, back in 1973, I wrote my own version of ELIZA in BASIC. I remember sitting there, so proud of myself for figuring out how to parse strings and flip "I'm afraid of cats" into "How long have you been afraid of cats?" It was the kind of thing that would be trivial for an adult programmer, but to me it was magic—this little piece of quasi-intelligence I'd created.

I had no idea at the time that this would turn into a decades-long quest. I certainly didn't know that my teenage BASIC program would end up being published in Creative Computing magazine in 1977, where it would be typed in by thousands of people with early microcomputers. And I definitely didn't know that if you've ever played with an ELIZA chatbot, there's a decent chance it was actually based on my code—or more accurately, based on someone else's version of my version of Bernie Cosell's version of something that wasn't quite the original ELIZA at all.

Fast forward to around 2000. I'd completely dumped AI and computers, deciding I wanted to become a marine molecular biologist. Screw computers, I thought. I wanted to pipette and grow algae. Of course, you can run but you can't hide from computers—I learned that later. But when I went into biology, I learned about phylogeny, and computational phylogeny, which was just coming up in the years after the human genome was sequenced. In microbiology, phylogeny is incredibly important because bacteria and viruses change really fast. The phylogeny of COVID matters a lot, for instance.

That's when it hit me: what if I could build a phylogenetic tree of ELIZA implementations? If I could measure the changes between all these different versions scattered across the computing landscape, maybe I could map out how they're actually related to each other. Not just historically, but computationally.

But here's the thing: for almost sixty years, nobody actually knew how the original ELIZA worked. Joseph Weizenbaum, who created it at MIT in 1964, never released the code. He published the algorithm, sure, but that was a different era—computer scientists prided themselves on describing algorithms, not "GitHubbing the code" as we'd say now. The code itself sat in a box in MIT's archives, unseen by almost anyone except Weizenbaum and maybe a few of his students.

Then COVID happened. And possibly the only good thing about COVID is that it made remote archival research practical. I reached out to the MIT archives, and a librarian named Myles Crowley got on a Zoom call with me. He pulled Box 8, Folder 1 from Weizenbaum's collection, opened it up, and held it up to his overhead camera. There it was: the original ELIZA code, printed out on that old continuous-feed paper that everyone my age remembers. We could die happy.

But finding the code was just the beginning. Understanding it required assembling a team—what we call "Team ELIZA"—including critical code studies scholars like David Berry and Sarah Ciston, and developers like Anthony Hay who could translate 1960s MAD-SLIP code (not LISP, as everyone thought) into something modern that we could actually run. And that's when things got really interesting.

What This Project Is Really About

This project started with a simple question: how can we reconstruct a genealogy of programs? Not the history as told in manuals or papers or people's recollections, but a genealogy grounded in the artifacts themselves—the code, the structure, the patterns that survive across generations of rewrites, ports, and reimplementations.

Software phylogeny—the project of understanding how earlier programs influence later ones—turns out to be surprisingly elusive. Unlike biological organisms with their (relatively) clear evolutionary pathways, software evolves through multiple mechanisms: direct copying, translation across languages, conceptual reconstruction from descriptions, pedagogical simplification, critical engagement, even deliberate parody. And it's not always clear what it means for one program to be "descended from" another, or even what it means for a program to be "the same" across different implementations.

ELIZA turned out to be the perfect test case for these questions. There are dozens—probably hundreds—of ELIZA-like programs scattered across the computing landscape, implemented in everything from LISP to BASIC to JavaScript to Rust. Some preserve the original architecture faithfully; others simplify it dramatically; still others invoke the name while rejecting the architecture entirely. The ELIZA family comprises a sprawling, poorly documented software "clade" that begs for systematic analysis.

So I decided to treat ELIZA implementations like specimens in a biological study. Over nearly two decades, I've been assembling a corpus at elizagen.org, collecting historical and contemporary versions from archives, repositories, forgotten servers, and personal code collections. And then I asked: can we build an actual phylogenetic tree of these programs?

The Method: LLMs Meet Phylogenetics

The core challenge was this: how do you compare programs written in different languages, using different paradigms, across six decades? You can't just compare source code—a pattern matching system in 1960s SLIP looks nothing like the same logic in modern Python. You need to abstract the programs into some common representation that captures what they actually do.

This is where things get interesting, and where my background in both computer science and cognitive science (yes, I left programming to study psychology at Carnegie Mellon, only to eventually go back to computers, which probably tells you something about me) came in handy.

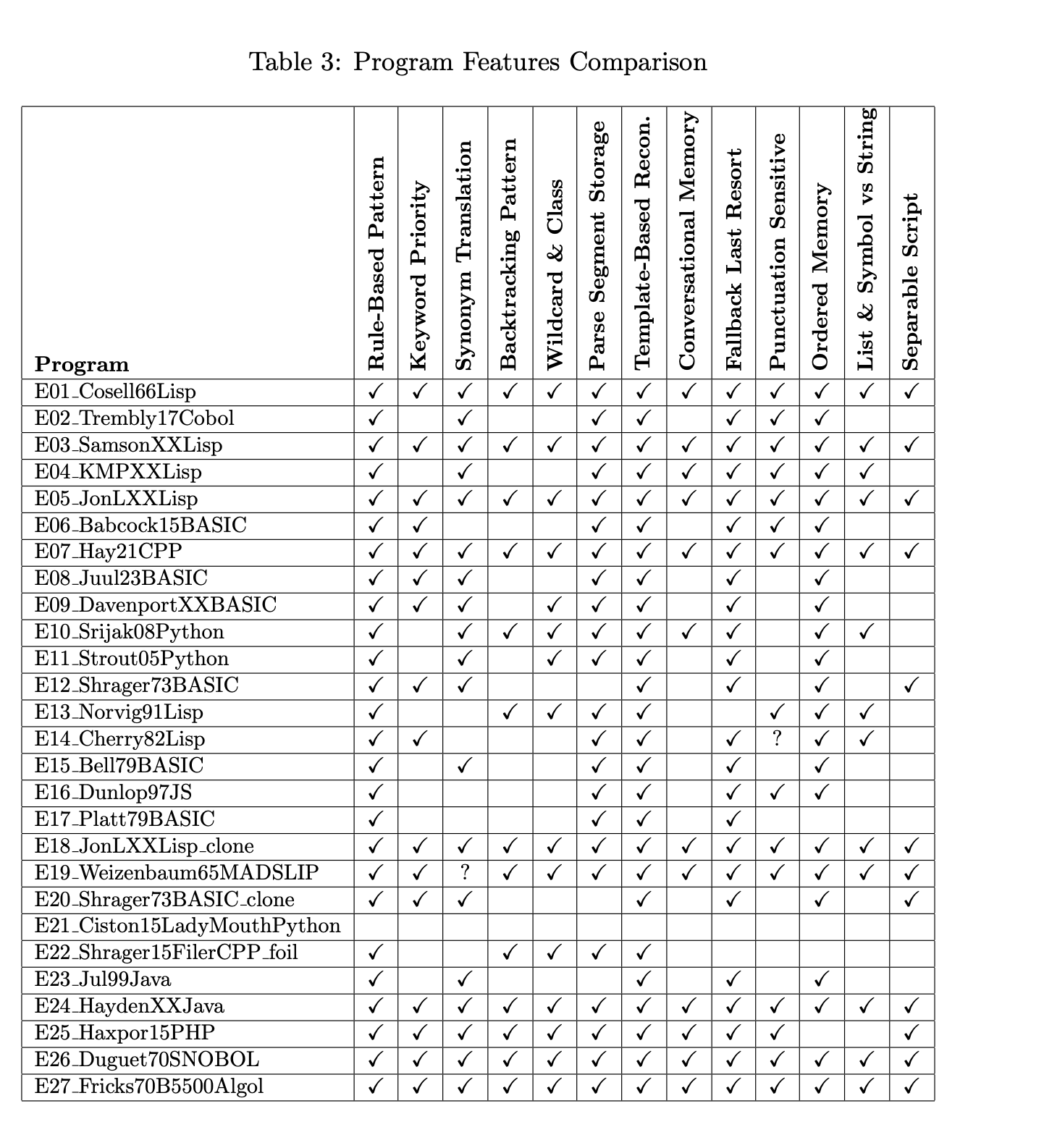

I used large language models to help extract features from each program. For every implementation in my corpus, I had an LLM identify the salient structural and behavioral properties: Does it use rule-based pattern matching? Does it assign priorities to keywords? Does it have a backtracking pattern matcher? Does it maintain conversational memory? And so on.

The resulting feature lists went into structured YAML files—essentially a "phenotypic" description of each program. But here's the thing: I didn't just trust the LLM output. I manually curated every analysis, adding features the model missed and correcting things it got wrong. And then I did something called "round-robin vocabulary expansion," where I iteratively showed each program's features to the model along with the aggregate vocabulary from all other programs, asking it to identify potentially missing features. This process continued until the vocabulary stabilized.

The final step was encoding these features as binary characters (present or absent) and feeding them into PAUP*, a phylogenetic analysis program used in evolutionary biology. PAUP* uses parsimony methods to construct trees representing relationships among specimens based on shared and divergent features.

The Specimens: A Diverse Corpus

My corpus includes 27 implementations spanning from 1965 to 2025 and eight programming languages. The full list is in the GitHub repository, but let me highlight some of the most interesting specimens:

The original and its immediate descendants: Weizenbaum's 1965 MAD-SLIP version (yes, MAD-SLIP, not LISP—that was a surprise), Bernie Cosell's 1966 LISP reconstruction (created from Weizenbaum's verbal description without ever seeing the source code), and several other LISP implementations from the 1960s and 70s.

The exotic language versions: A COBOL implementation, a SNOBOL version from 1970, and an Algol version that ran on the Burroughs B5500.

My own lineage: My 1973 BASIC version that got published and endlessly copied, spawning countless descendants in the microcomputer era.

Modern reconstructions: Anthony Hay's meticulous 2021 C++ version, Peter Norvig's pedagogical LISP implementation from "Paradigms of AI Programming," and various Python and JavaScript versions.

The outliers: Sarah Ciston's LadyMouth, a feminist critical art project that invokes ELIZA while rejecting its entire architecture, and a file system utility I threw in as a control specimen—it does pattern matching but has nothing to do with conversational AI.

I also included a pair of byte-for-byte identical clones as a validation test to make sure the method could correctly identify truly identical programs.

What We Found: The Tree Structure

The phylogenetic tree reveals two major patterns, and they're fascinating.

The Basal Polytomy: Architectural Completeness

The most striking feature is a large polytomy at the base of the tree—essentially a place where multiple branches emerge from the same point, indicating that these implementations are architecturally indistinguishable given our character set. This group includes:

These programs span six decades and completely different programming paradigms, yet they all preserve the complete ELIZA architectural suite: rule-based pattern matching with keyword priority, synonym translation, backtracking, wildcard tokens, parse segment storage, template-based reconstruction, conversational memory with ordered recall, fallback rules, punctuation-sensitive tokenization, list-and-symbol processing, and separable script architecture.

The fact that Cosell's independent reconstruction from verbal description clusters with the original is particularly meaningful. It validates both the robustness of Weizenbaum's conceptual design and the power of informal knowledge transmission in early computing communities. Similarly, the fact that Anthony Hay's 2021 C++ version clusters with 1960s implementations confirms that careful historical reconstruction can successfully recover the original architecture.

The Derived Clade: Simplification and Adaptation

Branching off from this architecturally complete core is a well-supported group showing substantial architectural divergence. This clade contains mostly BASIC implementations from the 1970s and 80s, along with various Python and JavaScript versions and some simplified LISP implementations.

These versions show patterns of feature loss driven by different constraints and contexts. The BASIC implementations that circulated through hobbyist magazines often lack backtracking pattern matchers and conversational memory—simplifications driven by the limited memory and processing power of early microcomputers, but also by pedagogical choices. These were programs meant to be typed in by amateur programmers and understood by beginners.

The Python implementations show different simplification patterns, sometimes preserving some features while abandoning others like keyword priority ranking or separable script architecture. These choices reflect how modern programming paradigms—object-oriented design, web frameworks—shaped how ELIZA's concepts got reimplemented.

Interestingly, Peter Norvig's LISP version from 1991 appears in this derived clade despite being written in LISP. It lacks several features present in the complete implementations: keyword priority, synonym translation, fallback rules, separable scripts. This was clearly a deliberate pedagogical choice—Norvig was illustrating core pattern-matching concepts in minimal, readable code, not trying to faithfully reproduce the complete ELIZA architecture.

The Validation Tests: What They Tell Us

The clone test worked perfectly: the two byte-for-byte identical copies cluster together with zero branch length, exactly as they should.

The control specimen—my file system utility—revealed something important and somewhat problematic. It nests within the derived ELIZA clade rather than appearing as an outgroup. This tells us that the thirteen characters we're using capture general pattern-matching program architecture rather than ELIZA-specific conversational features. A file utility and a chatbot can share enough architectural features to cluster together when we only consider structural characters.

This finding points to a refinement needed in future work: we should include features more specific to conversational coherence and therapeutic dialogue patterns that would distinguish chatbots from other pattern-matching systems. But it also makes a deeper point: structural similarity alone doesn't constitute participation in the ELIZA tradition.

The Extreme Outlier: Critical Engagement

LadyMouth scores zero on every single architectural character. No pattern matching, no keywords, no templates, no memory—nothing. Yet it explicitly engages with ELIZA through its name, its invocation of therapeutic dialogue, and its critical feminist examination of language, gender, and computational authority.

LadyMouth represents what I'd call critical participation in the ELIZA tradition—engagement through interrogation and rejection rather than preservation. Where canonical implementations accept the premise that therapeutic dialogue can be simulated through pattern matching, LadyMouth questions that premise by using fundamentally different mechanisms. Its maximal phylogenetic distance from all other implementations accurately represents its relationship: connected through discourse and positioning, distant through architectural choice.

What This Actually Means: Software as Textual Tradition

Here's where things get philosophically interesting. The phylogenetic tree we've produced isn't really a phylogeny in the biological sense, nor is it a classical stemma like you'd find in textual criticism of ancient manuscripts. It's something else.

The Problem with Rigid Designation

In biology, an orange is an orange because of material continuity—it grew on an orange tree that descended through an unbroken chain from ancestral citrus lineages. Philosopher Saul Kripke called this "rigid designation" in natural kinds: physical continuity provides the anchor for reference.

But software fundamentally lacks this anchor. You can recreate a program from scratch, guided only by a description, and end up with something functionally identical to the original despite sharing no material history. That's exactly what happened with Cosell's LISP version—Weizenbaum described the algorithm in conversation, and Cosell built it independently.

Moreover, programs get copied, modified, compiled, decompiled, translated across languages, and reconstituted from fragments. Each transformation can sever the "chain of custody" that would establish lineage in the biological sense.

So what counts as "an ELIZA"? If it's defined by specific architectural features, then many programs commonly called ELIZA aren't ELIZAs at all. If it's defined by the name and social positioning, then we're in the realm of convention rather than objective structure. And to make matters worse, many implementations conflate ELIZA (the language-processing framework) with DOCTOR (the specific psychiatric script), losing the platform/script separation that was central to Weizenbaum's original design.

Reframing as Textual Tradition

Instead of treating ELIZA implementations as imperfect copies of an original, I've found it more useful to view each as a distinct version within a textual tradition. This framework comes from literary scholarship—particularly Jerome McGann's work on "bibliographical codes" and D.F. McKenzie's "sociology of texts."

The idea is that each implementation exists in its own social and material context. A 1960s LISP version with terse variable names reflects the constraints of its time—scarce memory, expensive computing, programmers working in isolation. A modern Python version with extensive docstrings and type hints reflects contemporary norms of collaborative development and software engineering pedagogy. These aren't superficial differences; they're constitutive features of each version's identity.

Under this view, authenticity can't be located in an "original" (which few people besides Weizenbaum ever saw anyway), but rather in the integrity of each version within its own context. Each implementation is part of a tradition, bearing relations to what came before and enabling what comes after.

The Naming Paradox

This brings us to what I call the naming paradox. Self-identification through naming is actually the opposite of rigid designation. It represents intentional adoption into a tradition rather than material continuity.

Consider LadyMouth. It says "I am ELIZA" not because of descent but because of critical engagement with the ELIZA concept. My file utility shares architectural features with ELIZA but makes no such claim. In the textual tradition framework, both positions are meaningful data. When someone names their program ELIZA, they're performing an act of acknowledgment (recognizing the tradition exists), positioning (claiming a relationship to it), and interpretation (offering their understanding of what ELIZA means).

So the phylogenetic analysis doesn't become irrelevant when identity is socially constructed—rather, it reveals the structure of that social construction. The tree maps different modes of participation in a textual tradition: faithful preservation, adaptation through different contexts, convergent reimplementation, critical intervention through rejection.

What We Learned from the Original Code

Finding and analyzing the original ELIZA code revealed some surprises that challenge the conventional narrative:

It wasn't written in LISP. Everyone thought ELIZA was a LISP program, but it was actually written in MAD-SLIP—a list-processing extension to Michigan Algorithm Decoder that Weizenbaum had developed. Interestingly, Weizenbaum's paper on SLIP doesn't mention John McCarthy's LISP even once, which seems like a deliberate snub in the competitive world of early AI research. There's even a line in the SLIP paper that reads something like "some people love their homebrew programming languages too much, whereas what we really need is to put this in Fortran, which everybody uses." The irony is that LISP ended up being how most people experienced ELIZA, making it a showcase for the very thing Weizenbaum was implicitly criticizing.

ELIZA could learn. The code contains a whole teaching component that's mentioned only briefly in Weizenbaum's paper and was completely lost to history. You could type a command (I think it was "learn" or something similar) and actually train ELIZA in real time by entering new rules in the S-expression format. This makes the naming make more sense—it's called ELIZA after Eliza Doolittle from Pygmalion, who learns proper speech. But since nobody had the code, nobody knew it could actually learn.

It was a programmable framework. Weizenbaum's student Paul Howard extended it so you could put MAD-SLIP code directly into the script. The script itself could contain conditional logic and modularized sub-routines. So ELIZA was more like a framework for writing sophisticated chatbots than just a single chatbot. The DOCTOR script was like a "Hello, World" example, not the entire system.

The implementation details were sophisticated. Anthony Hay discovered that it used a hash function and had these two critical SLIP functions called Match and Assemble that did the pattern matching and response assembly. These functions weren't in the published SLIP code—we had to go back to MIT's archives multiple times to track them down. The code went all the way down through MAD, SLIP, and something unfortunately named FAP (an API to call assembly routines from Fortran), all the way to 7090 machine code. Anthony actually got the whole thing running in modern C++.

Where This Goes Next

This project is ongoing. We're still discovering things about the original code, still adding specimens to the corpus, still refining the character set to better capture what makes ELIZA-like programs distinctive from other pattern-matching systems.

A few directions I'm particularly interested in:

Better conversational features: The current character set needs features that specifically capture conversational coherence and dialogue patterns, not just pattern-matching architecture.

Wider sampling: There are probably hundreds more ELIZA implementations out there. I'd especially love to find more from the pre-microcomputer era, more from non-English-speaking countries, and more critical/artistic engagements like LadyMouth.

Other software families: The method we've developed should work for other software ecosystems with many descendants—adventure games, early operating systems, interpreters, AI toolkits. Any software family with a rich transmission history could be analyzed this way.

Theoretical development: I want to develop the theoretical framework further, thinking more carefully about how software traditions form, persist, and transform. How do naming practices work? What role do different types of documentation play? How do social networks of programmers shape what gets preserved and what gets lost?

Why This Matters

You might wonder why anyone should care about reconstructing the genealogy of a 60-year-old chatbot. A few reasons:

Understanding how ideas propagate: Software is one of the few domains where we can actually watch ideas spread, mutate, and evolve in something close to real time (at least on historical timescales). The ELIZA genealogy shows how a concept can be transmitted through verbal description, formal publication, code copying, pedagogical simplification, and critical engagement—often simultaneously.

Legal and practical implications: Questions of who copied whose code matter for copyright, patents, and software licensing. The phylogenetic approach offers a principled way to think about relationships between programs that goes beyond simple clone detection.

Historical methodology: Much of computing history is told through narratives and personal recollections, which are valuable but incomplete and sometimes contradictory. A computational approach to software artifacts offers a complement to traditional historical methods.

The nature of software itself: What does it mean for one program to be "the same as" or "descended from" another? These aren't just academic questions—they go to the heart of what software is and how it differs from both biological organisms and cultural texts.

For me, though, the real fascination is in the discourse problem. ELIZA was never really about AI or natural language processing in the modern sense. It was about conversation, about the back-and-forth that happens when you try to understand something or someone. That's what science is about too—you're having a kind of discourse with the domain you're studying, asking questions and getting answers back.

We still haven't solved discourse computing, even after sixty years of work since ELIZA. LLMs are impressive, but they're not having a conversation in the sense that ELIZA tried to have one—they're predicting text, not maintaining context and intention across multiple turns. The key insight from ELIZA, the thing that made people think they were talking to something intelligent, was that it reflected what you said back to you in a transformed way. It maintained a kind of coherence through the conversation.

That's what we've lost track of, and maybe why genealogy matters here. By understanding how ELIZA spread and what got preserved and what got lost in each transmission, we might rediscover what was important about it in the first place.

Acknowledgments

This project wouldn't exist without Team ELIZA: David Berry, Sarah Ciston, Anthony Hay, Rupert Lane, Mark Marino, Peter Millican, Art Schwarz, and Peggy Weil have provided years of invaluable discussion and technical help. Anthony Hay and Art Schwarz were particularly crucial for detailed technical analysis. Rupert Lane obtained the SNOBOL and ALGOL code. Myles Crowley at the MIT archives made it possible to access Weizenbaum's papers remotely during COVID. The Weizenbaum estate graciously granted permission to open-source the archival materials.

Some of the programming and writing for this project was aided by OpenAI and Anthropic LLMs, which is both ironic and appropriate given the subject matter.

All code, data, and source materials are available at https://github.com/jeffshrager/elizagen.org/tree/master/genealogy

This is a work in progress. If you have an ELIZA implementation I should know about, or if you find errors or have suggestions, please reach out. The methodology is solid but the corpus is always growing, and I'm still learning what these genealogies can tell us about how software evolves.

I read @jshrager 's work very carefully and noticed numerous similarities with the approach I adopted in analyzing the later versions of The Sumerian Game—whose source code was available—which led me to develop the family tree I posted above.

Unfortunately, a large part of my research was shaped by the absence of the original source code. As a result, everything I was able to discover and study depends on the surviving output printouts (relating to two gameplay sessions and therefore to only two versions of The Sumerian Game, namely Suilxr and Sum9rx), as well as on fragments of other outputs published in reports, newspaper articles, and memoirs written by some of the individuals involved in the project, including Bruse Moncreiff, the project’s originator; Richard Wing, curriculum research coordinator for BOCES; and Jimmer Leonard, who was responsible for reprogramming The Sumerian Game in Assembly and for developing the Free Enterprise Game.

In fact, Richard Wing was the primary source for much of the information that made the reconstruction possible, as he described in detail the mathematical model underlying the simulation. Thanks to his notes, his description of the game, and my analysis of the output listings, I was able to extract the text written by Mabel Addis—the teacher entrusted with designing the game—and to reconstruct the operating algorithms of the two best-known versions.

However, not all of the text has survived. In the preserved gameplay sessions that were printed and archived, certain events described by Wing in his account (for example, the flood event) did not occur. Therefore, while my reconstruction can determine when such an event takes place and calculate its impact (e.g., loss of food), it cannot reproduce the corresponding text written by Addis, since that portion has been lost.

In my view, this was the most fascinating part of the research: understanding how faithfully the game could be reconstructed without rewriting the missing narrative passages. With this in mind, I developed two versions of Suilxr (the game programmed at BOCES in Yorktown Heights).

The first version is more philologically faithful: when one of the two events whose text has been lost occurs, the program displays a placeholder sentence such as “missing flood text”, while correctly executing the mathematical calculations associated with the disaster.

The second version, instead, imaginatively reconstructs the missing portions. In this case, I recreated not only the narrative text but also the functioning of the slides and the interlude questions. Indeed, in the 1967 Suilxr version, the program would pose interlude questions to the player every two or three turns, both to break the monotony and to assess the student’s level of learning about Sumerian culture, history, and economics. Only one of these questions has survived, but using it as a model—and following Wing’s suggestion that they be categorized as easy or difficult—I recreated two or three dozen additional ones.

In upcoming posts, if there is interest in the topic, I could present the differences between the two original versions of The Sumerian Game: the one developed by IBM technicians and the one created at BOCES.

@andreacontato Actually, the whole idea of my approach was not to depend upon the original source code because so many many ELIZAs have been written in so many many languges. Rather, like pre-DNA biological phylogeny, it depends upon features (see figure below). PAUP can utilize any sort of feature table that applies to all samples. An algorithmic detail is optimal, and can be gathered either from source or from interpretation of the output or from an interview (and probably other ways). All one needs to do is produce a table that looks like this:

Yes, I understand. I did not explain myself clearly.

For example, I identified a feature—the land market—introduced by Douglas Dyment in 1968 in his King of Sumeria, which is present in all subsequent versions derived either directly or indirectly from it.

The same applies to the introduction of the final score (devised by Jim Storer in Lunar Lander and later incorporated into Pollution Game—which was itself derived from Hamurabi—and then adopted in David Ahl’s second version of Hamurabi, the BASIC version published in 101 BASIC Computer Games). That version became the most widespread one, from which the majority of Hamurabi-style games of the following years derived.

The only exception is Sumer (French), which does not include a final score because it derives from King of Sumeria in FOCAL-69 (as can be inferred from the way it generates event probabilities).

While the availability of source code certainly allows for a more complete analysis, I was nevertheless able to identify shared features and differences even in the games whose source code has been lost.